Joan Robinson Hill was a beautiful woman. Whip-smart, ambitious, and glamorous, she was “in all things a champion”—or so her epitaph reads.

When the Houston, Texas socialite was struck by a mysterious illness in mid-March of 1969, frew could have predicted that the otherwise healthy 38-year-old woman was days away from death. But even as Joan's husband, John Hill, a prominent plastic surgeon, raced Joan to the hospital and conferred with medical staff, friends and family noticed his extremely odd behavior.

Related: 6 Books By Edgar Award-Winning Author Thomas Thompson

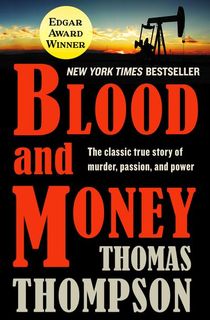

What happened next was a devastating blow to Joan’s family. Celebrated author Thomas Thompson chronicles this chilling case in his Edgar Award-winning true crime account, Blood and Money. Published in fourteen languages and with more than four million copies sold, Blood and Money dives deep into this shocking Texas tale of lust, greed, and murder, which sent shockwaves through Houston and beyond.

Read on for an excerpt of Blood and Money, and then download the book.

John helped load his wife into the back seat of her blue and white Cadillac, and Mrs. Robinson drew a light blanket over her legs. Just as they were preparing to leave, Ash Robinson drove up in his black Lincoln and got out with a worried look on his face.

“Great God almighty!” he swore. “What on earth has happened to this child?”

John repeated the news that Joan’s condition had worsened, that he felt it best she be hospitalized. He had chosen Sharpstown because she would receive “special care” there.

Ash leaned into the back seat and comforted his daughter. “How do you feel, honey?” he asked.

Joan smiled faintly.

“Do you want me to go with you?” he asked.

“I’m going,” said Ma.

With that, John started the car and drove away, leaving Ash standing in the driveway, worrying, wondering.

Related: Richie Diener: The Troubled Son Killed By His Own Father

It was approximately 11 miles from the Hill home on Kirby Drive to Sharpstown Hospital. It took John Hill almost three quarters of an hour to progress what could have been done in half that time. “He drove like a snail,” Mrs. Robinson would later say. “I felt we were never going to get there. In fact, it was almost like he did not want us to get there.

En route, John switched on a classical music tape, and the sounds of a symphony filled the Cadillac. At one point Mrs. Robinson snapped at her son-in-law, “Turn that damn music down, John. I can’t hear myself think.”

Mrs. Robinson kept asking her daughter, “Honey, how do you feel?” Several times Joan only nodded, but midway, she said, “Mother, I am blind. I can’t see you.”

Mrs. Robinson turned to her son-in-law. “Did you hear that? What does it mean?”

“She’s having a blackout,” said John. He did not seem concerned. He repeated his previous statement that the hospital was “alerted” and its emergency facilities geared up to receive Joan.

Joan Robinson Hill and her husband, John

Photo Credit: AlchetronBut when the car eased into the driveway that fronts Sharpstown Hospital, no team of emergency medical personnel rushed out to admit Joan Hill. In fact, no one seemed to know she was coming. John Hill got out of the car and went into the hospital. His mother-in-law sat for what seemed like several minutes waiting for someone to help her daughter. Finally John appeared with a nurse who was pushing a wheel chair.

Joan sat up in the back seat of the car, gasping for breath, while her mother pleaded, “Oh, God, hurry!” Joan was lifted carefully and put in the wheel chair and pushed into the hospital. Mrs. Robinson would learn later that the hospital had, in effect, no emergency room facilities at the time. And no intensive care unit whatsoever. The modest suburban hospital was, as one doctor described it in 1969, “a good place to have a baby or get a broken arm fixed—little else.”

“The sick woman was taken to a private room where nurses descended on her for the admitting process. Mrs. Robinson was asked to leave and did so, standing around helplessly in a corridor for more than an hour. John Hill seemed to have vanished as well, and she could find no one to tell her anything.

Related: The Claus Von Bülow Affair

Earlier that morning, John had telephoned a physician named Dr. Walter Bertinot who practiced internal medicine at Sharpstown. A capable man, he was nonetheless an unusual choice. Bertinot was not considered one of Houston’s many celebrated doctors of world rank, nor had he ever treated Joan Robinson Hill. He had, in fact, only met the woman once or twice, and that was to shake hands at the annual picnic which the Hills gave at Chatsworth Farm.

“Why me?” asked Dr. Bertinot. It occurred to him that perhaps John Hill should be treating his own wife, or that the lady’s personal physician might be more suitable to minister to her needs. John Hill’s answer was unusual. He said Joan did not really get along with doctors on a professional basis, but she had once spoken well of Bertinot. He made his wife out to be a problem patient, the kind doctors dread. Bertinot, a quiet, colorless, unemotional man with the character of a college physics professor, could handle a temperamental woman.

“What are her symptoms?” asked Bertinot. Diarrhea, vomiting, and nausea, replied John routinely. The Sharpstown doctor assumed then and there that Joan Hill was suffering from acute gastroenteritis. Or, in lay language, stomach flu. Bertinot was flattered to be asked to treat one of Houston’s most famous women, but there seemed no urgency to the matter. John Hill’s tone on the telephone was calm and unemotional. There was no mention whatsoever of “intensive care” as the plastic surgeon had told his mother-in-law and the maid.

The first nurse to attend Joan in her hospital bed took a blood pressure reading and was startled to discover that it was 60/40—perilously low.

The nurse was so concerned by the reading that she took it again, wondering if the apparatus could be malfunctioning. Once more Joan’s pressure read 60/40. An emergency call was made to Dr. Bertinot, who at that moment was a block away in a small professional building adjacent to the hospital.

“I dropped everything and went over,” Dr. Bertinot would later say. “I canceled out my whole schedule.”

When he first encountered Joan Hill, she was sitting up in bed and seemed flushed and short of breath. She did not appear to be a woman in shock, but she had to be in shock with a blood pressure of 60/40. Moreover, Joan greeted Dr. Bertinot by his first name, “Walter,” and smiled at him. All very curious. The doctor ordered IV fluids started immediately in an attempt to build up the blood volume and raise the pressure. The danger here was that the patient would be thrown into terminal shock unless the blood volume was restored.

Related: The Truth is in the Blood: The Murder of Tabatha Bryant

While the nurses rigged IVs, Dr. Bertinot methodically took Joan’s medical history, concentrating on the previous few days. Learning that she had been vomiting, suffering from diarrhea, and complaining of general nausea and malaise, he made a snap judgment that he was dealing with some kind of a dysentery, perhaps salmonella, food poisoning.

Routinely, Dr. Bertinot ordered urinalysis and stool cultures, for if Joan had eaten something that had precipitated food poisoning it could perhaps be determined by studying her feces to see if threatening bacteria were at work there. At this point the condition of his patient did not alarm him, for food poisoning is a common reason for admission to a hospital. But other factors about Joan intrigued him. Why did she seem so rational, when her blood pressure indicated that she was in deep shock? Confounded, Dr. Bertinot summoned a colleague, Dr. Frank Lanza, in consultation. Lanza, a flashy, fleshy young doctor who had once been a professional dancer and who performed a night club act to help his way through medical school, was but two years out of his residency in 1969. And though well trained, neither was he considered one of Houston’s most famous diagnosticians. Before many more days passed, questions would begin to arise as to why John Hill employed two doctors of the then lesser stature of Bertinot and Lanza to treat his wife, rather than engage physicians of world rank just across the city.

At this midday on February 18, 1969, John Hill was in the operating room at Sharpstown, performing an operation for removal of a scar, and listening to a broadcast of classical music.

Despite the IV fluids being dumped into her veins, Joan’s blood pressure remained low. Now it occurred to Dr. Lanza that perhaps the woman had septic shock, resulting from a massive bacterial infection somewhere in her body. She had, after all, complained to Effie Green of “burning up” from her neck down. The physician ordered more elaborate blood cultures to search for bacteria, but the trouble here was that the test would take perhaps as long as seventy-two hours. Blood must be placed in agar plates, a gel-like substance, and in this medium, bacteria—if present—will grow.

Joan Robinson Hill and her father, Ash Robinson.

Photo Credit: AlchetronBy late afternoon, six hours after admission to the hospital, a nurse noted that no urine was passing out of Joan’s body through a kidney catheter. This indicated kidney failure and was alarming to the attending doctors. They directed that the IV fluids be increased, hoping to stimulate the kidney into producing urine. While this was going on, Ash Robinson popped into the room, promising to bring his daughter yellow roses on the morrow, lingering until the nurses banished him.

Shortly after 8:00 P.M. her condition became grave. The increased IV fluids had not stimulated the kidney into producing urine, and the blood urea nitrogen level was elevated. A well-respected renal man, Dr. Bernard Hicks, was called in. It took him but a few moments to diagnose serious kidney failure.

Related: 8 True Crime Books About Murders in Texas

“Should we move her to Methodist?” asked Dr. Lanza. A dialysis machine was available at the cross-town hospital that Dr. Michael DeBakey had made famous. Such a machine could take over the work of a kidney, purifying the blood, while doctors tended to other threatening matters in Joan’s body.

“No,” answered Dr. Hicks. The woman is too sick to move. Instead he would attempt peritoneal dialysis, placing a tube in the stomach and forcing a blood-purifying solution first in and then out a second tube through osmotic pressure. The procedure turns the entire peritoneal cavity into an artificial kidney and can work as well as a dialysis machine.

Related: The Case of Michael Peterson—a Perfect Husband, or the Staircase Murderer?

Dr. Walter Bertinot watched, almost unbelieving. He could not have imagined that this critically ill woman before him was the same who had greeted him warmly 10 hours earlier and called him by name.

Dr. Hicks would not begin the peritoneal dialysis without approval from John Hill. Where was he? During the day he had been in and out of his wife’s room a few times, but now he was home. Effie Green took the call from the hospital and summoned her employer from his music room, where he was sitting alone, absorbed in a concerto. When he hung up, he hurried to the door, telling the maid, “We may lose Mrs. Hill. She is very sick.”

But although the call was made at 9:15 P.M., through the hospital switchboard, John did not show up in his wife’s room until 11:00. When he arrived his wife was conscious and, surprisingly, fairly lucid. A nurse present heard Joan beg her husband to stay with her because she was frightened by all of the tubes and contraptions attached to her body. The surgeon nodded agreeably, read her chart, then pushed a chair beside the bed and propped up his feet.”

Joan Robinson with her horse, Belinda.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsDr. Bertinot checked his patient half an hour after midnight and felt there was, if not slight improvement, at least a stabilizing. Blood pressure had raised slightly, and the peritoneal dialysis was working. Since the case was now more or less thrown into the lap of the renal specialist, Dr. Hicks, the physician in charge felt it was all right to go home and get some sleep. “I’ll stay a while longer,” said Dr. Lanza. “You go on home, Walter, and if anything happens, we’ll call you.”

John Hill, seemingly satisfied with the care his wife was getting, said he was going to spend the night on a couch in the patient records room, just down the hall.

At 1:30 A.M. on the morning of March 19, Dr. Lanza went home, as had Hicks, the kidney specialist, and Joan Hill was left in the care of nurses and a night resident who was in charge of the patient census. John Hill patted his wife gently and whispered that he would be just down the hall in case he was needed. Drifting now in and out of lucidity, Joan instructed the nurse to make sure that her husband was comfortable. Then she began composing a grocery list for a party she was giving, her mind wandering. The peritoneal dialysis was painful, but she was heavily sedated.

Related: 11 Gripping True Crime Book Bundles to Keep You Occupied While We Shelter in Place

An hour later the nurse noted that her vital signs showed indications of sudden heart failure. She ran to the doorway and called to the central nursing station to summon the resident with cardiac arrest equipment. At that moment Joan raised her head slightly from her pillow and gasped. “John!” she implored. Frantically she searched for air. Then a torrent of blood raced up from her innards and splashed out of her mouth, staining the pillow red-black.

Dr. Yama, the resident who was moonlighting from his position in radiology at another hospital, raced into the room and plunged adrenalin into the heart. But it was too late.

With that final agonal hemorrhage, Joan Robinson Hill was dead at the age of 38.

Want to keep reading? Download Thomas Thompson's Blood and Money today.

Blood and Money

An Edgar Award Winner and New York Times Bestseller: Thomas Thompson chronicles the “gripping” true story of beautiful Texas socialite Joan Robinson Hill, her ambitious doctor husband John Hill, and a string of mysterious deaths (Los Angeles Times) that sent shockwaves through Houston and beyond. Expertly told, Blood and Money is a tragic tale of murder, passion, and power, and a must-read for true crime aficionados everywhere.

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Lineup to continue publishing the true crime and creepy stories you love.

Featured photo: Alchetron