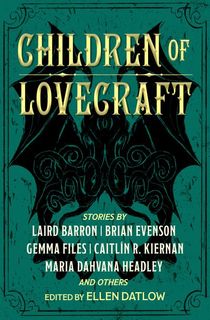

Children of Lovecraft is an anthology of prose inspired by the themes and plots of iconic horror author, H.P. Lovecraft. Although the anthology is based on Lovecraft’s work, it is completely original: there are no stories in his style, no pastiches, and no direct references to Lovecraft or any of his works.

With a large variety between the stories in terms of tone, setting, point of view, and time, this anthology is sure to keep you on the edge of your seat as you follow its many chilling twists and turns. Children of Lovecraft is edited by award-winning anthologist Ellen Datlow, who brings her impeccable taste and commitment to quality to everything she touches. Included are stories by Stephen Graham Jones, A. C. Wise, Caitlín R. Kiernan, John Langan, and more.

Continue reading to enjoy an excerpt from the short story “Little Ease” by Gemma Files, one of the stories featured in the Children of Lovecraft anthology.

Continue reading to enjoy an excerpt from the short story “Little Ease” by Gemma Files, one of the stories featured in the Children of Lovecraft anthology, then buy the book to read more!

"Little Ease," by Gemma Files

It came out of the dark, and into the dark it has gone again. —E. F. Benson

My name is Ginverva Cochrane, and five years ago I was roughly eighteen months into a gig as a freelance exterminator, doing unregulated pest control jobs for a private contractor who moved me from placement to placement, always keeping stuff off the books. It was shit work, basically— sometimes literally, always figuratively—and I’m not exaggerating when I say I took it on for lack of anything better.

You’re probably thinking,“I’ll bet she must’ve been on drugs, or drunk, or both.” Well, you’d be right. Shorter version of an already short story, without all the boring explication: car accident, dead best friend, botched recovery, painkillers and alcohol plus the side effects thereof, a truncated education, infractions to misdemeanors to a felony charge plea followed by a shortish stint in jail, crapped-out credit, and an ex-con stamp on my résumé. In the end, it took the events I’m about to recount to finally break me out of that overall downward spiral, for which I should be grateful, in retrospect. My last foster mother, Zillah, used to claim people eventually find the job they’re most suited for, as though employment were some kind of moral refining process you’d really have to put your back into fucking up. She believed that to allow yourself to work simply for money, swap time for cash in order to walk away at the end of shift, and spend the rest of the weekend thinking about anything other than Monday morning, was like you were cheating yourself on some cosmic level—that not giving a fuck about work was an insult to the universe, so you couldn’t claim to be surprised when the karma incurred through that sort of deliberate perversity came back to bite you in the ass.

I got my exterminator work through a woman I’d met in prison, whom I’ll call Leonora. She was a high school equivalency instructor, later admitting she used our test results to figure out which of us short-termers might be worth recruiting for her little side business. She once told me I had the highest scores of anybody she’d ever passed, but I’m pretty sure that was glad-handling BS; pest control isn’t exactly full of geniuses—it’s something any moron can learn to do, and I do mean that literally, given how consistently dumb everybody I worked with in that area turned out to be. I’m talking people who never read anything longer than the back of a cereal box or couldn’t calculate fifteen percent for tips, people who thought being a Muslim should be made illegal, people who called their pets “fur babies.” They were good enough to go out with for drinks on occasion, when the loneliness got too hard to handle, but that was about it.

Personally, I’ve always had a hard time not thinking about things, even when I know damn well I’d be better off if I didn’t. Dreaming can be a kind of drug, especially when you can’t afford anything better. Throughout my life, whenever things got really bad, I’ve felt this

overwhelming urge to lie down and open myself up, abandon myself to whatever might present itself—just turn off the light, shut my eyes, and let my own subconscious boil up from inside until it presses back down upon me, rendering me slack, heavy, irresponsible: guiltless in the face of my own choices, or lack thereof. Let it all wash over me, would be my last thought, before submerging; let me sink down, like a rock in the river.And lie there untouched, till the morning I don’t come up again.

Around the same time the events of this story took place, I started having a series of seemingly infinitely nested dreams that started one night only to cross over into the next, sometimes spilling into naps or reveries. Each new episode of the overarching narrative appeared to emerge from elsewhere, entirely outside myself; I’d wake with my sense of personal reality bruised and aching, actively questioning whether or not I’d actually experienced any of the things I devoutly felt I had.

Though these dreams varied widely in content, they always involved me finding a door somewhere no door existed, opening it, and going through. Once it was in the corner of my bedroom, lurking beneath the wallpaper; I only noticed it because the outline of its edges disrupted the pattern ever so slightly, a glitch in the design. Another time I got out of bed, crossed toward the bathroom, and heard something squeak beneath me—when I glanced down, I caught the glint of hinges, realizing only then that someone had cut a trapdoor in the floor without me knowing, leaving it waiting for me to stumble into. And once the door manifested itself inside my hall closet; I pulled aside the coats to reach for something deeper, paused, then saw the shadow between them was a hidden portal, barely cracked onto a deep expanse of black.

Doors, doors, everywhere. Wrestling through them before crawling on, unable to go back, afraid to go forward. After which I would wake from darkness into darkness and lie there sweat covered, pressing my hand down so hard it hurt over a hammering heart.

Pest control is a quotidian venture, at best; you can cull the overflow, but there’s always more, lurking inside the walls. Everybody assumes—correctly—that the bugs are there, but nobody really cares, so long as they don’t have to see them. And when you do see them that’s when you know you’ve got an infestation.

Similarly, the type of site you get sent to as an exterminator is usually determined by whether or not you’re okay working with rats, as opposed to whether or not you’re okay working with bugs. For myself, I find rats ten thousand times more disgusting than insects, mainly because they’re far more unpredictable. Didn’t help I’d once come across a nest full of newborn ratlings, all pink and squirming, blind eyes visible through their slightly transparent eyelids; really didn’t help I’d found it the same moment a bunch of male adult rats were chowing down on what might have been their own kids, while the mothers were off scavenging for dinner. After that, I was totally an insect person. I think most of us are, in context—almost nobody I’ve ever met has a problem with killing bugs.

Another thing I learned is that each site has its own peculiar ecology, which means that knocking out one insect type only replaces it with another—so that’s what you aim to do: maintain a careful natural balance that renders the inherent process of predator and prey invisible once more, without eliminating it entirely. Like managing climate change (supposedly), but restricted to one particular neighborhood, one block, one apartment building.

The sites I got sent to had a lot more in common than insect infestations, however. Inevitably, they were owned by one of a small, tight knot of local slumlords, while the buildings themselves ran the gamut from mildly rundown to outright decrepit. We’re talking exposed wiring, cold-water plumbing, bucket toilets, broken everything. Garbage piled up in the corners, sometimes rotting—the easiest fix, so long as I could find somebody English-fluent to translate my suggestions about better hygiene equaling fewer bugs. The residents I interacted with tended to be nomads and refugees, seasonal workers, people too old, broken, or poor to move, the illegal and the indigent: a constantly exploited floating class of paperless, voteless, voiceless drones who the city’s legitimate social infrastructure probably wouldn’t piss on if they were on fire.

I tried to tell myself I was doing something positive for these people, at least indirectly. That by ridding these places of pests, I was playing intercessor between these unfortunate residents and the system trying to game them, not just greasing the machine’s wheels in mid-crush.

Leonora had deals with a bunch of different pesticide companies, buying expired products in bulk at a discount to keep her overhead down, and handing them out to us like they were brightly colored poison candy. One night, after being dumb enough to casually Google the names of the various sprays and powders I routinely handled, I discovered that almost all contact insecticides are literally nerve agents, organophosphates specifically designed to interfere with the enzymes that enable bugs’ systemic impulses. Even the most benign have more in common with sarin gas than anything else, and multiple exposures only amplify their toxicity, creating a cumulative effect that can denude a whole area.

Our on-site safety protocols were put-on-rubber-gloves-and-hold yournose-type shaky. If we wanted masks, we paid for them ourselves, so most people went with the molded cotton kind plasterers use. I combed through military surplus stores till I came up with a chemical warfare rig from Desert Storm, but soon found out nobody made filters for it anymore. So I just cobbled my own together out of reconstituted, cut-down sanitary pads, and hoped I wasn’t breathing in anything too permanently damaging.

Because it felt like I had no other choice, I sucked it up; played through the grime and the itchiness, the sore spots and intermittent waves of queasiness, the head-to-toe stink that never quite went away. I refused to chart symptoms, convinced stress was just as likely to cause everything I was experiencing, even as my shower’s drain clogged up with hair and my face took on a hectic rosacea-patterned glow, flaky-flushed across the forehead, the thin-skinned arch between eyebrow and lid. Like I’d been trying to tan using a microwave.

Thirteen weeks in, however, I hit the wall hard, forced to admit what I really should have known all along: I was hip-deep in toxins and risking my health for a pittance, stuck fast, with no immediate way I could figure out to extricate myself.

“C’mon in here, Ginnie,” Leonora told me one Monday, when I came in to load my car up with whatever awful shit they were handing out that week. “Need to talk to ya about the job you’re on … Dancy Street again, right?” I nodded. “Yeah, okay; won’t take a minute. And shut the door, will ya?”

Inside Leonora’s office sat a tall woman she introduced as the “Dancy Street Project’s” general manager, whose name I recognized from all my previous paychecks, but who I’d never before seen in person. She wore a suit and a little too much perfume, both probably expensive.

“Nice to meet you, Miss Cochrane,” she said, smiling wide. “Leonora tells me you’re a pretty smart cookie.”

“I like to think so,” I agreed, already wary. People say women are more empathetic than men, which is why we socialize quicker and get along better. But most of us only learn to fake that empathy to deal with men’s egos, rather than each other’s; some of the worst jobs I’ve ever worked had all-female crews, especially when you got somebody ambitious enough to want credit but too shameless to put in any effort, yet duplicitous and clever enough—as Suit-chick already struck me—to shove any blame for the ensuing eff-up onto ground-level cannon fodder like me.

She nodded. “You’ve been onsite how long now?”

“At Thirty-Three? Well, I started last Tuesday—”

“—But Ginnie’s been our point gal on a number of jobs in the area over the past few weeks,” Leonora chimed in. “So she’s more than familiar with the current state of the project.”

I moved my head, noncommittally, while Suit-chick just kept on smiling.

“Mmmm,” she said. “And what’ve they got down there, in your opinion?”

“Basic infestation,” I replied. “I’d guess roaches, by the damage.” I waited for her to ask if I’d seen them myself, but she didn’t, which struck me as weird, even then. As it happens, I’d seen every-thing but: black pepper–flake feces with a musty, pungent odor, plus oothecae—oblong casings like a caterpillar’s cocoon, housing fifty eggs each. I’d found them all over Thirty-Three, fresh-popped and ready to go, either glued up under counters, clustered round the groins of pipes, or in the dusty corners of ceilings where nobody thought to check, especially people too frail to crane their necks that high.

“Looks like they came out of the walls,” I continued. “I’ve been laying down poison, but I’m still not seeing carcasses. What I really need to do is knock a few holes and look around inside, get a handle on what they’re doing back there. I put in a request.”

“Yes, we saw that.”

“Um, okay, great. So … can I?”

Her smile didn’t change, at all. “We’d actually prefer that you didn’t.”

The Dancy Street area—Project—was a weird little cul-de-sac jammed between a slow-dying semi-industrial area and pre-gentrification’s encroaching decay. Their nearest neighbor had once been the Winnick Brothers Camp-out Cookery plant, home to a defunct brand of easy-heat tinned stew; “pet food for people,” a guy I once dated used to call it. But they’d been gone since the short-fall crash, leaving nothing behind but a few crumbling buildings, a bunch of equipment too heavy to move and too obsolete to sell, plus a ground-in smell of dead flesh that emerged whenever the heat climbed too high, strong enough to make a hyena gag. Number Thirty-Three was an apartment building dating back to the 1920s, a moldering gray-brown brick box put up for the Cookery’s live-in staff housing, then given some shoddy build-on action and sold as a combination halfway house and backpackers’ drop-in. Now it was a crapped-out threestory inhabited by maybe fifteen extraordinarily old people, all of whom I’d run into in the halls, by this point. I’d see them stringing laundry up between the bottom balconies inside the all-concrete courtyard as I came out of the basement, shoes crunching slightly over its cracked and broken areas; they’d smile, or seem to, and I’d try to smile back.

Most I couldn’t have described if you’d paid me extra, not even to tell the (presumably) men from the (presumably) women—just a bunch of hunched little figures at the corner of my vision, all with the same sort of wispy gray hair, gray teeth, gray faces.

The sole exception was a lady I called Great-Aunt Chatty, if only in my head. She’d sidled up behind me my second day onsite, taken a long, squinty gander over my shoulder, then asked, “Are you sure you should be using that indoors, dear?”

“That” was Leonora’s latest load of whatever-the-hell, a vile pink paste I was currently spooning out of a bucket and smearing along the baseboards on either side of the cellar door. “Just doing what it says to on the label, ma’am,” I lied, without looking up.

“Miss,” she corrected, gently. “Are you from the property office?”

“Um … sure.”

“Then you’d be able to pass along a message for me, if I asked.” This, however, was further than I felt comfortable going, in terms of polite bushwah. “Not really,” I replied, forcing myself back to a standing position, so I could seem slightly more official. “I’m just here to deal with the bugs. You’ll need to talk to the superintendent about anything else.”

“Oh, truly?” I nodded. “Because none of us have seen that particular gentleman in quite some time now, you know; three months, perhaps even six.”

“I can’t help you with that, ma’am—miss.”

“What a pity.”Adding, after a pause,“I wasn’t aware we had insects.”

“Seriously?” She raised one surprisingly well-kept brow. “Well, my boss wouldn’t’ve sent me out here if you didn’t.”

“I suppose not, no.” Indicating the paste: “Will that help?”

“Hopefully.”

“And if it doesn’t?”

I sighed. “We switch to something else.” Half to change the topic, I turned to face her and saw she fit the pattern of an Orthodox spinster, Jewish or otherwise: no makeup, long hair in wound-up braids, collared shirt and a dark skirt to the ankles, her once-good black shoes gone dusty and cracked with age. “Miss, no offense, but what’s someone like you still doing … here?”

“Someone like me? I’m not quite sure I know what you mean, dear.”

“It’s just … you seem—” Sane? Human? “—like you might have options.”

“Ah, well. I’ve spent the last few years working on a private concern, a very particular line of inquiry; a scholarship, one might say. And despite its difficulties, this is the single best location for it I’ve found, as yet.”

Sounds legit, I thought. But at that same moment, it was like a scrim dropped down over my eyes, like the hallway itself gave a single, slow, rippling blink. Two thoughts at the same time, super-imposed: an image from my dreams sharpening quick into focus, darkening the daylight. The idea of crawling farther and farther in through successively smaller spaces, tunnel narrowing till it touched your skin, only to find you no longer had room to turn round, even if you wanted to: just stuck there, hot and close, jacketed in your own flesh like a ready-made coffin. Neither here nor there, forever. “Oh, yeah,” I heard myself answer, from far away. “I know how that goes. Like when you get so far into a thing, dig in so deep, you just, you can’t … get back out again.”

“Something like that, yes.”

“Like—an enthusiasm. Or an obsession.”