Even if you’re a film buff, you can’t deny that there’s something creepy about old silent movies. The grainy film quality combined with the lack of sound can just make things seem a little off or disconnected. All of this makes silent films a perfect subject for horror. What kinds of century-old secrets could be hidden in those old reels?

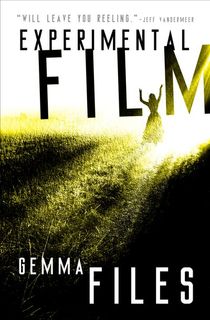

That’s exactly the question Gemma Files sets out to address in her Shirley Jackson Award-winning novel Experimental Film. The book follows Lois Cairns, a former film teacher turned freelance critic. These days, she spends most of her time caring for her autistic son and attending film screenings. At one of these screenings, she discovers an intriguing piece of very old silent film footage.

Related: 9 Chilling and Mysterious Old Hollywood Deaths

After some research, she manages to trace the small bit of film to Iris Dunlopp Whitcomb, a spiritualist and fairy tale collector famous for her mysterious disappearance in 1918. Inspired, Lois begins an ambitious research project to prove that Whitcomb was the first female filmmaker in Canada. But what she finds is far more than she bargained for. It seems the fantastical creatures from the stories Whitcomb collected may have been more real than she could have ever imagined. As she continues her research, the past and the present seem more interconnected than ever, and Lois is drawn into a supernatural struggle to protect herself and everything she holds dear.

Related: 25 Female Horror Writers That Will Haunt Your Bookshelves Forevermore

Experimental Film is an exciting tale of horror with fascinating elements of film history throughout. Files’ own experience as a film critic definitely adds to that aspect of the story, and she’s not afraid to take you through Lois’ research methods in ways that are just as gripping as any classic horror scene. In the excerpt below, you’ll see Lois in the thick of her investigation. Once you’ve read it, buy a copy for yourself! Have some popcorn handy once you do, but be warned: you might want to keep the lights on for this cinematic experience.

Read an excerpt from Experimental Film by Gemma Files below and then purchase the book!

Even as I connected the dots on Wrob’s methodology, I was also watching this new footage emerge, politely at first but a bit restively, squinting to get some sort of purchase on what I was seeing, then with growing interest. By the last flicker, less a fade than a smash cut to black, I was riveted.

Now the thing is, I could fill this whole chapter with film-critic jargon if I wanted to, all cues and references and shorthand. But I learned the hard way how most people— even ones who actually work in the industry—just don’t care about that sort of accuracy. I remember one class, early in my teaching career, where a student to whom I’d just returned a script covered in scribbled comments raised his hand and asked: “Miz Cairns, you said here that the character development was ‘cursory.’ What’s that mean, exactly?”

“It means you didn’t have enough of it. Did a half-assed job, basically.”

“Then why didn’t you just write ‘half-assed’?”

“Because there’s a word for it. And that word is ‘cursory.’”

Rather than drowning you in cinematographic esoterica, therefore, I’ll give you my most immediate impressions from that first viewing—the actual notes I scribbled down while still squinting up at the screen, done on a Staples notepad I rummaged out of my pocket.

very bright black + white, looks more like

grey/silver

bits come away? like its moulting

scratches pops dropped frames

this is old/1920s? silent film

older?

I remember what looked like sheaves of grain waving back and forth, or the shadows of very tall grass, sharp under a pitiless sun that must surely have been an effect, since battery-powered electrical lamps were not available during the period in which Mrs. Whitcomb made her films but a painted backdrop could be made to look flatly three-dimensional, as if going away into the distance the theatrical suggestion of a field, with people onstage in front of it, wearing archaic, fairy tale peasant-type clothes— smocks and leggings, jerkins, hoods that hid their faces, mediaeval, like a Dance of Death.

And then there was a woman, stepping out from behind them, either around the backdrop’s edge or through a cunningly hidden slit cut into it. She was brighter than everything else yet far harder to see in any true detail, covered as she was in a whitish veil that draped from her head to her feet and dazzled, sewn perhaps with glassine sequins, or tiny shards of mirror. She leaned down to whisper in one figure’s ear, dwarfing him—was he played by a child? A child with a false beard, recoiling from her with his hands up?

Cued, her own hand came out from behind her back, and I could see she held a sword, angling it to reflect till it had almost turned white: curved and sharp like a sabre, like the blade of a scythe. So bright it hurt the eyes.

At which point, the screen went black.

“Typically uninterested in any film except his own, Wrob Barney gives pride of place to Untitled 13,” my Deep Down Undertown article begins, “a waking dream of troubling things, done flammably, in light and poison.” Then again, though, I really wasn’t one to talk: there were ten other movies on that program, and I barely remembered any of them—Alec Christian got on my case about that, later on. I just couldn’t stop thinking about the way Barney’s piece made me feel, itchy in a good way, like the grit before the pearl. I needed to know where that came from.

I got home around one in the morning. Clark had probably been asleep since eight-thirty or nine, and Simon had dozed off in bed with the lights still on, a roleplaying game module balanced haphazardly on his chest. I could hear the two of them sawing counterpoint from either end of the apartment, a wracking, swollen-tonsils duet that wasn’t doing much for my burgeoning migraine. The older I get, the more I find that any sort of barometric pressure shift goes straight to my sinus cavities, ruthlessly crossbreeding what sometimes feels like a near-constant case of PMS with the general side-effects of crap vision versus watching movies all day (and night) to create organic lens-flares. I knew I’d need a potentially dangerous amount of Melatonin, muscle-relaxants, and recreational web surfing before I could safely count on being able to dodge a full-blown bout of insomnia.

So I started the usual late-night round of chores—load of laundry, load of dishes—and set my laptop up on the “dining room” table, an unwieldy glass-topped ironwork monstrosity Simon’s parents had bought us in anticipation of parties we’d never throw and meals we’d never make, not once it became clear that sitting still for social situations was something Clark seemed unlikely to ever do for more than ten minutes at a time. I transcribed my notes, moved stuff around, dashed off two thousand words’ worth of description and analysis, then signed onto our WiFi, readying the article to post.

Throughout the process, I kept on thinking about the film, replaying it in snatches till it overlaid the mundane details of my life. It was seriously driving me nuts, because the masks, the costumes, the hint of a story . . . it all reminded me of something, and I just couldn’t remember what. Not a movie, I knew that much; I thought maybe a photo, or a picture, so I hit PUBLISH, then pulled out my reference books and started going through them: stuff on fairy tales, stuff on mythology, on the occult, woodcuts, engravings, chiaroscuro, collage—Ernst, Magritte, Khnopff, Bosch, Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo. Movie stills. Comic books. Surrealists and Decadents of all descriptions.

Slowly but surely, as my perception narrowed, the presentiment of pain I’d been wrestling with became pain itself, dim but distinct: my eye sockets lit up, muscles on the back of my skull humping and crawling. I got sick, sleepy. Eventually, I had to force myself to sit down and stay quiet for a while, lids lowered, taking deep, slow breaths. Press my thumbs against my nasal bridge and watch the patterns form, hypnagogically recursive—red spiraling away into black, thicker and thicker, making it impossible to tell which was which.

Olfactory hallucinations came next, tinnitus garnished.

To my left, I smelled hay and smoke and mould, a whole burning barn of fragrances; to my right was wet earth, cold green shoots, frozen decay. A forest, deep and dark, after the late autumn rains.

Quiet, then. A long, grey pause, empty of almost everything.

When I opened my eyes once more it was almost four in the morning, but the pain was gone. Better yet, I finally knew what I was looking for.

I still have the text in question today, bookmarked between pages 112 and 113, where the section titled “Dreams & Nightmares” begins—a battered trade paperback with fraying laminate corners, the cover a murky reproduction of Emily Carr’s 1931 painting Among the Firs, called Finding Your Voice: Creative Writing Prompts and Projects, Grades Three to Eight (edited by Luanne Kellerman, copyright 1979 from Seedling Press, Toronto). It’s a compilation of fifth-grade English class prompts that struck enough of my fancy to make me “forget” to bring it back at the end of the year, all based on poems and essays, myths and fairy tales; mostly Canadian Content, too, because that must’ve been the most affordable option. It usually is.

Nothing to show what I wanted it for, at least not on the outside. But we all know the spine of a book tends to crack where you’ve read it most, even if it was so long ago it now seems unfamiliar, from the inside-out.

So when I opened it, this is what I found.

LADY MIDDAY

A Fairy tale of the Wends

Collected and Translated by Mrs. A. Macalla Whitcomb

First printed in The Snake-Queen’s Daughter: Wendish

Legends & Folklore

Once, a young boy was ploughing a field to ready it for planting, during the noon hour. How hot it was, and how he wished he could be elsewhere! His whole hatband was soaked with sweat. But his father was dead and his mother took in sewing to pay their way, and there was no one else to help him with his labours.

Soon enough, when the sun was at its still point above him, there came by Lady Midday, so tall and fine with her long white hair and her blazing eyes, and a terrible great pair of scissors in one hand, with blades so sharp and polished they threw back the sun’s rays like lightning.

“It is a hard day for ploughing,” she said to the boy, “and you without even a cup of water. Do you not wish for rest and comfort?”

But the boy’s mother had warned him of Lady Midday. So he kept his eyes to his task, bowing low in deference at the same time, and replied: “No, milady, for this field must be ploughed and planted, so that my mother and I may have crops to sustain us this winter. I need nothing, though I thank you for your kindness.”

At this, Lady Midday’s eyes flashed like a sword heated red-hot, thrust deep into the very heart of the fire, and she bent herself double to put her face right up next to the boy’s so that her hair fell around them like a veil. Whereupon the heat of her was so great the boy thought either he would smother, or that his cheek would crisp like bacon.

“Oh,” she said, so sweetly, “but you are a good boy, to do your mother’s bidding thusly! Do you not wish to stop and drink a bit, if only to refresh yourself once more for the work you have yet before you? See, I have brought water in a cup, cool and deep. You may have it all, if you will only turn to look my way.”

Yet the boy did not, shaking his head and bowing still further. “No thank you, milady, for I cannot turn myself from my work, and am not fit to look upon such sights—for how is it that I, a poor boy, could count myself the equal of such a personage?”

“You think me fair?”

“I know it, milady.”

“But only by report. Turn now, and see.”

How he yearned to do so! Yet the heat of her was so dreadful, parching his mouth and setting his skin to sizzle, and the light she gave as bright as though the sun itself sat on her shoulder, an ornament for her long white hair—hair which was neither plaited nor tied, but dropped straight down to her feet, so bare and dainty, whose nails were great claws made from brass.

“I cannot, milady,” he answered. And he closed his eyes in fear, though he ploughed on, that he might not have to see the terrible scissors descend.

All at once, however, Lady Midday withdrew her attentions, and her voice became gentle, though no more like a human being’s.

“Because you have been diligent and polite,” she told the boy, “and answered me with the courtesy due my station, I will give you for a gift that so long as the sun’s eye falls upon it, your field will flourish.

And I will not bother you again.”

And indeed, after that, she never did.

Further on, a grown man ploughed his field, cursing his lot and the sun’s pitiless stare. He beat his mule hard enough to draw blood, complaining all the while, instead of giving his task the attention it merited. And since the noon hour was not yet done, the sun at its still point above him, there came by Lady Midday in all her awful finery, to ask—

“It is a hard day for ploughing, and you without even a cup of water. Do you not wish for rest and comfort?”

The man raised his eyes from his task and looked at her straight on, haughtily. “What a stupid question!” he replied.

“It is hotter than the hobs of Hell out here. Is that water in your hand?”

“It is. May I take it you find me pleasant to look on?”

“Indeed, you are a fine, tall baggage. But how foolish you must be! Can you not see I am dying of thirst? Give me that cup, and quickly!”

“I think not,” Lady Midday told him. “Yet because you have not answered me with the courtesy due my station, I will give you for gift something very different.”

With that, she attained her full height, blazing so bright that the man went blind. Which is why he did not see to duck when she brought her scissors down with a great snip, cutting his head clean off.

“Now go home, if you can,” she said, “and have your wife sew this back on for you. Then wait until your sight returns and do your work with more diligence from now on, living the rest of your life in fear, for there are those in this world far less merciful than I.”

The man made his way home in terror, by long degrees— stumbling wild with his head hugged tight in his arms, unable to see where his feet were taking him—and never more dared to step outside until the sun had fallen. But for the rest of his life he felt Lady Midday’s eye upon him, always fearing to look too far up or too far down to avoid it, lest the stitches rip and his head fall clean off once more.

Want to keep reading? Click below to get your own copy of Experimental Film by Gemma Files!

Featured image: Jeremy Yap / Unsplash