Before fingerprinting, mugshots, and instantaneous global communication, skipping town was a simple solution for those suspected of—or convicted of—crimes. Many infamous killers, like H.H. Holmes or Jane Toppan, were able to extend their reigns of terror simply by leaving the town or state when suspicion flew upon them. But Thomas Cream took this to a new level, leaving whole countries behind after his crimes.

In Dean Jobb’s latest true crime excursion, readers will meet the infamous Dr. Cream. Cream, who grew up in Canada, had already been imprisoned for a murder in Illinois when he made his way to London under a modified name.

Convicted for the death of his lover’s husband, Cream was also suspected in the deaths of three women in Chicago, as well as his first wife’s death in Quebec, when he arrived in London as Thomas Neill. Soon, he would become the scourge of a rapidly transitioning city as the Lambeth Poisoner… and even be suspected of being Jack the Ripper.

Read on for an excerpt of The Case of the Murderous Dr. Cream and subscribe to Creepy Crate for your chance to receive a copy!

Mary Cream was only fourteen when her oldest brother left home to attend medical school. She remembered fragments of his troubled life—mentions of his stints as a doctor in Ontario and Chicago, his conviction for murder. When she saw him again in Quebec City in the summer of 1891, for the first time in close to two decades, she could scarcely believe what he had become. “He was most wild and excitable,” she remembered. “Not right in his mind.”

Cream had arrived in Quebec City on August 2, shortly after his release from Joliet. His family had emigrated from Scotland to Canada when he was four and settled in the capital of the province of Quebec. His father, William Cream, had managed a major timber exporting firm, amassing a fortune by the time of his death in 1887. Cream spent almost six weeks in the city, staying at the home of his brother Daniel. Relatives began calling him Thomas Neill. “He wished and decided to drop the Cream,” noted Thomas Davidson, a Quebec businessman and family friend, “on account of his unfortunate troubles.” No one seemed to suspect he might have other motives for changing his name.

Related: Amelia Dyer: Victorian England's Cruelest Baby Farmer

“His actions at times were that of an unsound mind,” Jessie Read, Daniel Cream’s wife, would recall. “He would change countenance and appear as another man,” excited and manic at one moment, quiet and vacant-eyed the next. Davidson, who attributed Cream’s “mental derangement” and “unbalanced” mind to his long imprisonment, was appalled when Thomas lashed out “in a most scandalous manner” at one of his sisters, possibly Mary Cream, calling her a streetwalker and a liar. These “atrocious slanders,” Davidson later noted, were repeated in a letter Thomas fired off to his sister’s friends.

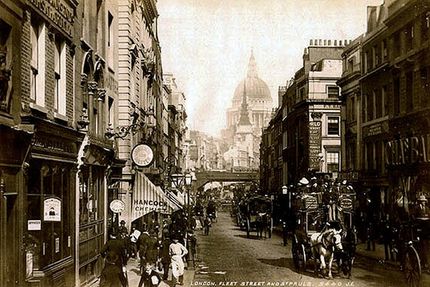

1890 photo of Fleet Street, London taken by James Valentine.

Photo Credit: Public domainDavidson and Daniel Cream devised a plan to send him abroad. A fresh start, they reasoned, might improve Thomas’s mental as well as physical health. It would, at least, free them from the strain of dealing with his erratic and abusive behavior. As executors of William Cream’s will, Daniel and Davidson withdrew a sum from the estate—the equivalent of twenty-three thousand US dollars today—that would help get Thomas back on his feet. Daniel considered sending him to Glasgow, near his birthplace in Barony, perhaps to visit relatives there. They settled on London, a city Cream knew from his days at St. Thomas’ Hospital in the late 1870s. A transatlantic steamer could deliver him to Liverpool in just over a week, but they opted to dispatch him on a slower, sail-powered ship. “We believed,” Davidson explained later, “that the long sea voyage and the complete change of scene would restore him to both mental and bodily health.”

On September 9, the night before he was to sail to England, Cream wrote a will. He claimed to be “of sound mind” and, oddly, named his sister-in-law, Jessie Read, as his executor and sole heir. In the event of his death, she would inherit all his property as well as any- thing he might be owed from the estates of his deceased parents. Did Cream feel a sense of imminent doom, that he would not be returning from England? The two-paragraph will, written in the neat, upright lettering that would soon be familiar to Scotland Yard detectives, offered no insights into his motives.

Related: House of Horror: The Brutal Murders at Georgia's Corpsewood Manor

He left Quebec City the next morning. On October 1, after a twenty-day voyage, he scribbled a note to Daniel Cream, announcing his arrival in England.

*****

Cream became a regular at Gatti’s Adelaide Gallery Restaurant on the Strand. The restaurant’s decor was elegant—vaulted ceilings, stained glass, ornate plasterwork, a palette of blue and gold—and it was a favorite of the theater crowd. Actors and playwrights from nearby playhouses claimed many of its marble-top tables. One day, when most of the seats were taken, he shared a table with another man.

He introduced himself as Thomas Neill. He was educated, tastefully dressed, and “well informed and travelled, as men go,” the other diner recalled. They shared meals many times, with Cream preferring bread and cheese, washed down with beer or gin, to the plovers’ eggs and other delicacies on the menu. He spoke about how much he enjoyed attending the city’s music halls. He talked about money and seemed obsessed with poisons. But most of the time, he talked about women.

“His language about them was far from tolerable or agreeable,” his dining companion had to admit. Cream carried around a collection of pornographic photographs, which he delighted in showing to his new friend and to other diners. He was restless and fidgety and could not stand still, even when drinking at the restaurant’s bar. And he was always chewing something—gum, tobacco, or the end of a cigar, his jaws “moving mechanically like a cow chewing the cud.” He seemed wary of every patron and waiter who approached his table. He rarely smiled, and his laugh sounded forced and fake, as if he were the villain in a melodrama. And people could not help but notice that his left eye turned inward, giving him a crazed, sinister look. Cream later claimed he had come to London to consult an eye specialist, and one of his first stops after his arrival had been the office of a Fleet Street optician. James Aitchison diagnosed his condition as hypermetropia, or farsightedness—his eyes focused improperly, blurring his vision and causing severe headaches. Cream had been suffering from the condition since childhood, Aitchison concluded, and had needed glasses for years. He supplied two pairs of spectacles to correct his vision.

Medicines containing strychnine, Dr. Cream's preferred poison.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsThe more his dining companion learned about Cream, the more troubled he became. “He was exceedingly vicious, and seemed to live for nothing but the gratification of his passions,” he remembered. “His tastes and habits were of the most depraved order.” And he made no secret of his drug use. Cream was constantly taking pills, three or four at a time, that he said contained cocaine and morphine as well as strychnine, a deadly poison used in minute quantities as a stimulant in medicines. The pills relieved his headaches, he said. They were also, he seemed delighted to add, an aphrodisiac.

Related: The Deadly Elixir of Giulia Tofana

Getting narcotics and poisons in London, Cream had discovered, was easy. He called at a chemist’s shop on Parliament Street— just around the corner from Scotland Yard’s new headquarters—and identified himself as a doctor from America, visiting the city to take courses at St. Thomas’ Hospital. The clerk, John Kirkby, could not find the name Thomas Neill in the shop’s register of licensed physicians. “I am not in the habit of selling poisons to persons whose names I cannot find in the register,” he would say later. Access to poisons was restricted by law, and if Cream could not prove he was a doctor, he should have been required to produce someone known to the pharmacist to vouch for him. But Kirkby made an exception and took this new customer at his word. He filled Cream’s orders for opium and strychnine several times that fall. When Cream asked for empty gelatin capsules of a size not in general use in Britain, Kirkby helpfully tracked them down from a supplier. Doctors and druggists filled them with medicine too bitter tasting to be taken on its own.

Cream did not say how he intended to use the strychnine or the hard-to-find capsules. Kirkby did not ask.

Want to keep reading? Subscribe to Creepy Crate for your chance to receive a copy of The Case of the Murderous Dr. Cream!

This post is sponsored by Algonquin Books. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Lineup to continue publishing the creepy stories you love.