For millennia, humans have been obsessed with the idea of death: how to delay it, how to prepare for the afterlife … and how to come back from the grave.

Necromancy is the practice of communicating with and raising the dead. It has been studied, taught, and tested throughout history.

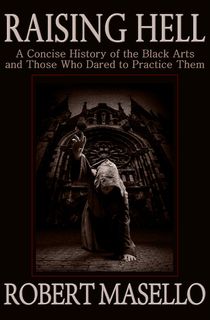

Robert Masello is the award-winning author of multiple works, including the cult horror classics Private Demons and Black Horizon. In Raising Hell: A Concise History of the Black Arts and Those Who Dared to Practice Them, Masello invites us on a fascinating journey through the dark history of necromancy. Indeed, the author makes clear that black magic and the occult are nothing new; our yearning to connect with the spirit world and harness its otherworldly energies is as old as mankind itself. And those individuals who practiced the dark arts did far more than procure bodies and chant magic words—although that happened, too.

Related: 52 Best Horror Books from the Past 200 Years

For instance, serious necromancers were forbidden from eating salt or meat (other than the meat of a dog, since dogs were the creatures of Hecate, goddess of ghosts and death). Some necromancers were also forbidden to look at women. In medieval Spain, necromancy was taught like any other discipline, with classrooms constructed beneath cemeteries and mausoleums.

As these seekers searched for meaning through magic, they also unearthed verifiable truths. Early astrologers mapped out the heavens above. Alchemists, hoping to transform matter and find a universal elixir, laid the groundwork for chemistry and discovered everything from phosphorous to the means of manufacturing steel. Even the soothsayers, those who interpreted dreams and claimed to see into the future, contributed to a greater understanding of the human mind and anticipated such later practices as psychology.

Related: 11 Chilling Ed and Lorraine Warren Books

Thoroughly researched and wondrously rendered, Masello conjures in Raising Hell a sweeping survey of the major occult arts—necromancy, sorcery, astrology, alchemy, and prophecy—as they have been practiced from ancient Babylon to the present day. Whether tracing the origins of occult symbols like the sacred circle and the pentagram, reviving the incantations and prophecies issued forth by 14th-century seer Nostradamus, or unearthing long-lost tales of ancient rulers who turned to necromancers in times of distress, Masello's Raising Hell offers a fascinating look at the history of the black arts—and those who risked their lives and their souls to explore them.

In the excerpt below, Masello delves into the history of necromancy and the story of Sextus, son of Roman leader Pompey the Great, who asked a witch to divine the future of his next battle with help from the spirits.

Read on for an excerpt and then download the book.

The History

Of all the black arts, undoubtedly the most dangerous was necromancy—the summoning of the dead. In a way, it was the pinnacle of the magician’s art, the most extreme and impressive feat he could add to his professional résumé. In part this was due to its difficulty—the ritual requirements were extraordinarily elaborate—and in part it was due to the great risks any magician was expected to encounter the moment he summoned ghosts and devils from the underworld. These spirits were often quite unhappy at having to make the trip.

So why bother them? Necromancers had all kinds of motives, some of which were more pure than others. Spirits were sometimes conjured up out of affection—the magician missed a loved one who had departed this vale of tears.

Related: Memento Mori: Remembering the Dead Among Us

Sometimes spirits were summoned up because the sorcerer wanted the arcane or secret knowledge that only spirits were reputed to possess.

And sometimes—perhaps quite often—spirits were called upon to divulge the whereabouts of hidden treasure hoards. It was generally understood that the dead may have lost their lives in the normal sense but that they had gained the ability in the afterlife to uncover all secrets and see into all things. According to the common folklore, these spirits could be found loitering around their burial place for one year after their interment. After that, however, getting in touch with them became increasingly difficult, if not impossible.

Not that it was ever easy. First, the proper location had to be found to perform the magical rites. Some of the preferred spots for necromancy were underground vaults, hung with black cloth and lighted with torches, or forest glens where no one was likely to intrude. Crossroads were popular, too—perhaps on the theory that many souls, both living and dead, were accustomed to passing by. Ruined castles, abbeys, monasteries, churches, were all considered good venues, as were, of course, graveyards.

The best time for necromancy was, as might be expected, midnight to 1:00 A.M. If a bright full moon hung in the sky, that was fine. But even better was a tempestuous night, one filled with wind and rain, thunder and lightning. And it wasn’t just for effect. Spirits, it was thought, had trouble showing themselves and remaining visible in the real world, but stormy weather for some reason helped them in their efforts.

Related: Bolivia’s Day of the Skulls

The necromancer had many preparations to make. In the nine days preceding an attempt to raise the dead, he and his assistants were required to steep themselves in every way imaginable in the gloom of death. They took off their normal, everyday attire and put on faded, worn clothes that they had stolen from corpses; as they put them on for the first time, they were required to recite the funeral rites over themselves. And until the actual necromancy had been performed, they were forbidden to take these clothes off.

There were other restrictions, too. They were not allowed even to look at a woman. The food they ate had to be taken without salt, because salt was a preservative—and in the grave, the body, putrefied, did not remain intact. Their meat was the flesh of dogs, for dogs were the creatures of Hecate, goddess of ghosts and death, whose appearance was so terrible that anyone conjuring her was warned to avert his gaze; one look at her, and the mind would be destroyed. And, in a kind of necromantic version of the Holy Communion, the bread they ate was black and unleavened; their drink was the unfermented juice of the grape. These symbolized the emptiness and despair of the realm they were about to explore. In all these preparations, the aim was to create a kind of sympathetic bond between the necromancers and the souls of those they were hoping to summon.

Once everything was in order, the necromancer and his accomplices went to the churchyard and, by the light of their torches, drew a magic circle around the grave they were planning to disturb and set fire to a mixture of henbane, hemlock, saffron, aloes, wood, mandrake, and opium. After unsealing the coffin, the body was exhumed, then laid out with its head to the east (the direction of the rising sun) and its limbs arranged like those of the crucified Christ.

Related: 13 Witchcraft and Occult Books to Get You in the Spirit of the Season

Next to the body’s right hand, the necromancer placed a small dish, burning with a mixture of wine, mastic, and sweet oil. Touching the corpse with his wand three times, the conjurer recited a conjuration from his grimoire. Though the wording of these conjurations differed from book to book, one of them went: “By the Virtue of the Holy Resurrection and the agonies of the damned, I conjure and command thee, spirit of [the name of the person] deceased, to answer my demands and obey these sacred ceremonies, on pain of everlasting torment. Berald, Beroald, Balbin, Gab, Gabor, Agaba, arise, arise, I charge and command thee.”

In a slight variation, if the soul being summoned had committed suicide, the sorcerer was required to touch the cadaver nine times and invoke it using other powers, including the mysteries of the deep and the rites of Hecate; he could also ask it why it had cut short its own life, where it resided now, and where it was likely to go hereafter. The spirit was enjoined to answer the sorcerer’s queries “as thou hast hope for the rest of the blessed and the ease of all thy sorrow.”

If all went well, the spirit reentered its old, cast-off body and caused it slowly to stand up. In a weary, sepulchral voice, the deceased would answer each question the necromancer put to it—what lay beyond this world of tears, which demons were causing us harm, where a buried treasure might lie. When the interrogation was over, the sorcerer rewarded the spirit for its cooperation by assuring it of undisturbed rest in the future; he burned the body or buried it in quicklime, which would dissolve it. Either way, the spirit knew the body would be gone, and it could never be forced to enter it again.

Grave Encounters

Sextus, the son of Pompey the Great, had a similar experience with a witch. He, too, was wondering what the outcome of a battle would be; his father was campaigning to become ruler of the Roman empire, but when Sextus tried to find out from the oracles whether the campaign would succeed or not, he got such confusing answers he threw up his hands in disgust. According to Lucan, who recounted the story in his Pharsalia, Sextus decided to consult with the celebrated witch Erichto.

This wasn’t a step to be taken lightly.

Erichto was a frightening creature, who’d been mixing up her personal and professional life for many years. To facilitate her communications with the dead, she had taken up residence in a graveyard, sleeping in a tomb, surrounded by bones and funerary relics. When Sextus asked her to look into the future for him, she said they’d first have to get hold of a fresh corpse.

Related: 9 Engrossing Books About the Science of Death

Luckily, there was a battlefield quite nearby, and after they’d combed over the casualties for a while, they found the body of a recently slain soldier that Erichto said would suit them just fine. The fact that his body was still warm indicated that the energy of life, which could quickly dissipate, was still there. Just as important, he hadn’t been wounded in the mouth, lungs, or throat; if he had been, he might not be able to talk once they’d gone to all the trouble of reviving him.

Together, Sextus and the witch dragged the body into a cave, which was concealed by yew trees and consecrated to the gods of the underworld. There, Erichto went about fixing a ghastly stew, using the flesh of hyenas that had fed on the dead, the skin of snakes, the foam from the muzzles of mad dogs, and assorted, foul-smelling herbs. When the vile concoction was ready, she ordered Sextus to cut a hole in the corpse of the soldier, just above the heart, so she could pour in this new substitute blood.

Then she began to recite her incantations, calling upon Hermes, the guide of the dead, and Charon, who ferried dead souls across the inky waters of the river Styx. She appealed to Hecate and Proserpine, the queen of the underworld, and Chaos, the dark lord whose aim was to spread destruction and discord among men. She reminded them all that she had always been their faithful disciple, that she had poured out human blood on their altars and sacrificed infants in their names. From the sky, thunder pealed, and all around the entrance to the cave Sextus could hear wolves howling and snakes hissing.

But Erichto kept up her chant, and gradually Sextus could make out the spirit of the dead soldier, hovering in the dark air above its own mangled corpse. Erichto ordered the spirit to reenter the body, but the spirit refused; she ordered it again, threatening to dispatch it straight to Hell. The spirit still wouldn’t do it. Then she tried a different tack: if the spirit would do her bidding, she said, she promised to utterly destroy the corpse; that way, no other magician could ever use it to perform such an awful rite again.

Related: 10 Best Horror Books and Paranormal Classics

This time the spirit acquiesced; it entered the corpse, and the blood began to circulate in its veins, the limbs twitched with life, and slowly, unsteadily, the body rose up on its feet. In halting speech, it described for Sextus the dismal outcome of his father’s campaign—the imminent battle would be lost, and Sextus himself would die an early death. But when it had finished, and Sextus was satisfied that he had received the true, if unhappy, news, Sextus and the witch built a funeral pyre, and the dead soldier stretched himself out on it. True to her word, Erichto recited a spell that freed the spirit from any earthly bonds, and the pyre was set ablaze.

Want to keep reading? Download Raising Hell.

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Lineup to continue publishing the true crime and creepy stories you love.

Featured photo: Yann Schaub / Unsplash