On November 29th, 1909, police arrived at a dilapidated New Jersey home to find Oceana “Ocey” Snead—a 24-year-old single mother—lying dead in her bathtub. Her clothes, piled on the floor, bore a suicide note that cited her sickly children and missing husband as "pain and suffering greater than [she could] bear."

Though Snead’s death appeared to be an open-and-shut case, doubt crept in once investigators noticed oddities around her house. Not only did it have an air of near-vacancy—it lacked working heat, and there was almost no furniture—but its other primary resident, Snead’s Aunt Virginia, had been disturbingly slow to report the incident. She justified her 24-hour delay by feigning ignorance, saying she'd simply obeyed her niece's demands for bathroom privacy.

Ocey Snead in 1907, two years before her death.

Photo Credit: AlchetronBut the police weren’t so convinced, especially after they spoke with Snead's doctors. She weighed less than 80 pounds at the time of her death, having suffered from months of malnourishment and chronic illness. One doctor even said that Snead seemed to live in a constant state of fear.

Furthermore, Virginia’s sister, Mary, and Snead’s mother, Caroline, behaved strangely during the investigation. The three women wandered around the home, wearing all-black dresses and floor-length veils in a showy display of grief. When pressed for explanations of Snead's poor health, they offered bizarre reasons for not aiding her recovery. But it was their collection of $32,000 in life insurance money that finally exposed the truth: Snead may have suffered from depression, but she had not taken her own life—her family had.

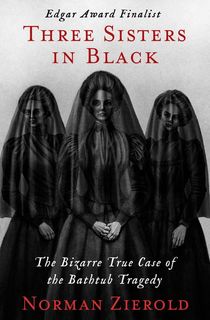

The true crime book, Three Sisters in Black, recounts this mysterious "bathtub tragedy," including the sinister plot hatched by Snead's relatives and a shocking final police discovery. The following excerpt takes readers to the beginning of the case, when Virginia reported Snead's death suspiciously late.

Read on for an excerpt of Three Sisters in Black, and then download the book.

At 388 Main Street, East Orange police headquarters, Sergeant Timothy Caniff picked up the receiver. He noted the time as 4:40 P.M. At the other end of the line a woman’s voice, soft and cultivated, asked whether a coroner could be sent immediately to her house. There had been “an accident.” The sergeant explained that the county had no coroner’s office; he would send out a physician. The soft voice gave an address, 89 North Fourteenth Street, and hung up. Unable to reach the county physician, Caniff called his assistant, Herbert M. Simmons. Dr. Simmons walked to the designated location from his nearby office, crossing the Lackawanna Railroad overpass, then continuing three short blocks on North Fourteenth Street before reaching number 89, a cheerless gray frame house of two stories topped by an attic.

Medical satchel in hand, he was climbing the porch steps when the front door opened. Before him stood a tall spare woman dressed all in black, a long cape flowing to the ground, heavy veils secreting the face. Startled by this somber apparition, the physician was relieved to hear the pleasing accents of the South in the voice that beckoned to him.

“Please come in,” it said. “I am Virginia Wardlaw.”

Related: Lizzie Borden's Secret Motive for Murder?

“Simmons identified himself. Silently, the woman in black led him up a flight of stairs and down the second-floor hallway. Open doors along the way gave no sign of occupancy. At the end of the hall, the woman halted. Simmons hesitated, knowing he was about to see what he had come for, the intractable face of death.

For the physician it was an everyday experience, and yet one to which he was never fully reconciled. Steeling himself, he turned the knob, pushed the door, saw that he had entered the bathroom. There it was, the nude body of a young woman in the small, half-filled bathtub. The slender figure was in a crouching position, legs doubled up at the knees, the left hand lightly grasping a washcloth, the head submerged in the cold bath water and tipped slightly to the right, directly under the faucet. Long auburn hair streamed like a fan on the water. The physician gently raised the head and saw a face that must in life have been very beautiful—each feature fine and classically formed, dominated by large brown eyes now fixed in a sightless stare.

After a preliminary inspection of the body, Simmons’s attention shifted to a pile of clothing on the floor. To one of the garments a note was pinned. The physician read the bold clear handwriting:

Last year my little daughter died; other near and dear ones have gone before. I have been prostrated with illness for a long time. When you read this I will have committed suicide. Do not grieve over me. Rejoice with me that death brings a blessed relief from pain and suffering greater than I can bear.

O. W. M. SNEAD

“Who is this woman?” Simmons asked the veiled figure in the doorway.

“She is my niece, Ocey Snead. She has been despondent since her first child died last year. Then her husband died seven months ago. She also has a four-month-old son who is ill in St. Christopher’s Hospital in Brooklyn. She herself has been in very poor health.”

“When did you find the body?”

“Only a short time before I called the police station.”

At this reply, the physician looked up sharply. He tried to control his voice so that accusation would not enter: “But this woman has been dead fully twenty-four hours.”

“Well, perhaps she has,” answered Virginia Wardlaw. “The truth of the matter is, she asked me yesterday afternoon to start a fire in the kitchen range to heat water for her bath. She was about to take a nap. I started a fire and then, having business to attend to, went away, leaving her to sleep undisturbed.”

“Were you two living alone in this house?”

“Yes.”

“And in twenty-four hours you never made inquiry, never went to see how she was when she didn’t appear at meals or before bedtime?”

“She had asked not to be disturbed, did I not tell you?”

“The rooms in this house seem empty. Why are you living like this? Why haven’t you any furniture, or any comforts?”

“It has suited us to live this way. We had only settled here temporarily.”

Despite his efforts to appear casual, Simmons’s tone had become increasingly challenging; that of his interlocutor had grown cold, almost disdainful. Virginia Wardlaw refused to reply at all to further questioning and asked the physician to complete his business as swiftly as possible. On leaving, Simmons noted again the empty rooms, the lack of heat in the cold, bleak house. At the nearest telephone he called the police station, reporting the case as an apparent suicide but with suspicious elements that warranted sending a detective.

Related: Little House of Horrors: Laura Ingalls Wilder and the Bloody Benders

An hour had passed since the original call to the Main Street station. It was nearing six o’clock and night had fallen when Sergeant William H. O’Neill knocked at number 89. The curtains were drawn. It appeared that a dim gas lamp burned within. When the door opened the woman in black stood framed in the entranceway, demanding to know the sergeant’s business. He had been ordered to inspect the premises, he explained. In caustic tones, she said she did not understand why, then turned and led the way upstairs. In the bathroom, O’Neill saw the body and read the suicide note. He asked to see the rest of the house.

The tour started with the attic. It was completely empty. Returning to the second floor, O’Neill thrust his head first into one room, then into a second, and a third. Each was empty, with only a silk maternity gown in a closet bearing mute witness to the life that had ebbed away. A fourth small room opened over the porch. In it stood the narrow cot which had been the dead girl’s last bed. By the pillow O’Neill found a locket containing the photo of a smiling baby. Two pins held a tag which read: Lock of David Snead’s first hair Aug. 18, ’09. On the floor lay a pair of dainty shoes and a fine black silk gown, evidence of onetime affluence: also a broad-cloth coat with silver lining and white silk facings on the lapels. Near the cot was a barrel covered with a white cloth. Combs and hairpins indicated it had been used as a makeshift dressing table. On a box in the corner stood a package of cereal and empty cans that had contained evaporated milk. Bits of oranges and orange peelings were scattered around the room. The only element of decoration to relieve the pathetic squalor was a painting of a ballerina on one wall.

Bare floors rang hollow to O’Neill’s tread as he made his way through the house, the shrouded figure in black following silently, her sepulchral aspect made more sinister by the dim gaslight. In the downstairs hall a chair missing front legs was propped on an ordinary soapbox; piled on it were embroidered coverlets that might once have graced a divan. The parlor was bare save for a corner stand holding a solitary umbrella. In the dining room the table consisted of a packing box with an improvised plank top. A lone chair had been fashioned by nailing a willow chairback to a dry goods box. A closet contained a large quantity of cheap unbleached muslin which had evidently been used to blanket windows in the house. The gloomy kitchen was dirty and unkempt; morsels of food lay strewn about. Finally, in the cellar a heater of ancient vintage was hopelessly out of repair, with not even an ash of coal remaining.

Ocey Snead two years before her death.

Photo Credit: AlchetronTragedy seemed to be in the very atmosphere of the house, symbolized by the black raiment of its only remaining occupant, Virginia Wardlaw, to whom O’Neill now addressed himself, standing facing her, for neither of the makeshift chairs seemed adequate for sitting. The detective regretted the stiffness, the discomfort of thus confronting her. His observance of her movements had convinced him she was elderly, perhaps close to sixty years of age. Her mind, however, was sharp and quick. O’Neill found the answers to his questions parried adroitly. The basic story remained the one she had told Dr. Simmons: Ocey Snead had been ill and despondent since the death of her first child, Mary Alberta, early in 1908. The death of her husband in March of the current year had added to her sorrows, which seemed to have no end. Her second child, David, born in August, had been sickly and they were forced to place him in St. Christopher’s Hospital in Brooklyn.

Who was Ocey Snead? What was her maiden name? Where was she born? These questions the woman in black refused to answer. What was the husband’s name? Where had he died? Were there other members of the family nearby? Again, silence or evasion.

“Let me go and I will notify the girl’s relatives and “then return to you,” the woman suggested.

Her offer was refused.

“How long have you lived in East Orange?”

“Perhaps ten days.”

“Why did you come here?”

“For Ocey’s health. I came along to nurse her.”

“For her health? To this empty house, with no heat and no furniture?”

“I have answered your question as best I could.”

“There’s only one cot. Where did you sleep?”

“On the floor. Must you continue asking these questions? It does not seem quite fair. By what right do you ask them?”

Detective O’Neill ignored this sally and continued his interrogation. Was it possible that two people could live together in a small house, the one sickly, the other not checking on her condition for twenty-four hours? Yes, came the reply, for Ocey had asked not to be disturbed. Had her absence not been noted at mealtime or upon retiring for the night? No, for she, Virginia, had come and gone, tending to errands. Had she not had occasion herself, in twenty-four hours, to use the bathroom? No. Had Ocey left the house during this period? She did not know.

Related: 9 Famous Female Ghosts Who Will Scare You Senseless

“You’ve only been here ten days. Where did you live before?”

“In the flatlands section of Brooklyn..”

“Where in the Flatlands section?”

“Must you go on like this? Must I answer that?”

“I will find out eventually.”

“At East 48th Street and Mill Lane. Now may I be allowed to rest?”

With his first substantial clue in hand, Sergeant O’Neill was not about to leave his quarry. To the unhappy woman before him he explained that she would have to come to the police station. She did not protest. Carrying only the small bag already in her hand, she stepped ahead of him, leaving the mournful house of death to which she would never return.

At headquarters, Chief of Police James Bell questioned the woman in black—who emphasized that she was Miss Virginia Wardlaw—from early evening until midnight without making any further headway. To the chief, she seemed cunning, skilled at hiding key facts. Finally, he booked her for the night as a material witness, then drove her to the Essex County Jail, fifteen minutes away on Wilsey Street in Newark. There were too many loose ends, too many unexplained circumstances. Who exactly were these people apparently of a better station in life yet surrounded by squalor? Why this secretive manner? Would a young woman in a weakened troubled condition write a suicide note in so clear, so unwavering a hand? Was the note in fact genuine? How could Ocey Snead have summoned the resolution, the strength of will to hold her face under water until death? Would not the human spirit have asserted itself, convulsively, instinctively rejecting so grim an act? Was it possible, Chief Bell asked himself, that another hand than her own, a sinister and malevolent hand, held her head under water until life slipped away?

Want to keep reading? Download Three Sisters in Black now.

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Lineup to continue publishing the horror stories you love.