The year is 1936, and Arthor Crandle’s life has fallen to pieces. Stressed by marital issues and even worse financial troubles, he finds work as a live-in assistant to an enigmatic, ailing author. But when Arthor moves into the man’s Providence home, he realizes that nothing—especially his employer—is what it seems. For one thing, the place is most certainly haunted, filled with ghost-girls and a creepy, hovering presence. Meanwhile, his boss only gives orders through letters slipped beneath his door, refusing to leave his room or reveal his name...And then there’s the arrival of Flossie, the beautiful Midwesterner who’s come to stay while her friend, Helen, is away. The only problem? Arthor has never seen, or heard of, another boarder named Helen.

As the bizarre occurrences turn more and more terrifying, Arthor has no choice but to pry into his employer’s past. Only then does he discover the true story behind the happenings at Sixty-Six College Street—and that he’s working for none other than H.P. Lovecraft.

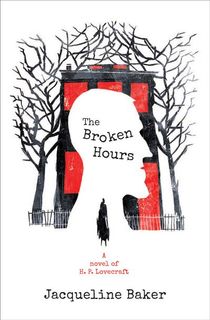

Published in 2014, The Broken Hours serves up maximum haunted house eeriness as Arthor tries to untangle a web of dark secrets. Aside from paying tribute to Lovecraftian lore and style (yes, a tentacled creature does make an appearance), Jacqueline Baker also borrows elements from the author's personal history—including his late-in-life destitution and Rhode Island roots. Though H.P. Lovecraft is one of the biggest names in classic horror, he died without fame or money in 1937.

The following excerpt of Baker's novel takes place just after Flossie confesses her fears about Helen, who is still worryingly MIA. Her imagination has cooked up wild theories—what if someone like Albert Fish attacked her?—that Arthor tries his best to refute. But during a walk in the woods, the pair makes a shocking discovery, and Arthor has a realization that's as frightening as any serial-killing Gray Man...

Read on for an excerpt of The Broken Hours, and then download the book.

The weathered blue and green canning shacks ranged like a shantytown along the water. Gulls circled and cried. A fine cold mist blew in from the sea. The islands out in the bay had blackened and the sky over the gray water swirled darkly. The black ship was still there, inching toward the horizon in the paradoxically heavy-weightless way only massive vessels built to float could. The air smelled of wet rot, of the bottom of the sea churned to the surface. There was an odd electricity, as if far out on the water, something terrible gathered and swelled. Flossie cast questioning glances at me now and again. I knew not what to say. About anything.

She lifted her head and breathed deeply.

That air, she said with obviously forced cheer.

Is putrid, I finished.

Instantly, I regretted it. Flossie looked hurt. I was not angry. Or, at least, I was not angry with her. I was angry, certainly, with my employer. Perhaps with myself. A familiar story. I felt the beginnings of another headache.

Flossie stopped on the boardwalk and looked down the beach, one hand shading her eyes, the wind in her yellow curls. The romantic pose was not lost on me, as I supposed was her intention. I pretended not to notice and peered hard out at the horizon. The ship I’d seen only a moment ago had disappeared. I scanned the bay but could find no sign of it.

What are those people doing down there, do you think? Flossie said.

She pointed to a small group standing looking at something on the sand near the edge of the foul water. Gulls cried and lifted and circled in the ruckus. Low waves rolled bleakly in. My eyes drifted out, past the shoals, to the low line of light along the horizon. Where had the ship gone? It bothered me. Gulls, something, wheeled erratically in the high wind, far out. I put my hands on the rail and the wood was damp and swollen and splintered beneath my palms.

Arthor? What are those people looking at?

I haven’t the foggiest.

Related: 11 Books for Fans of H.P. Lovecraft

Flossie clicked down the rickety boardwalk and I followed. Her heels sunk into the sand at the bottom and she wobbled, taking my arm.

Perhaps we should go back, I suggested. Something’s blowing in. And you’re hardly dressed for a day at the beach.

She shot me a pointed look.

A girl’s got to dress for something, she said, and I had the odd sense she’d said this already.

Then, slipping her shoes off, she set out determinedly in her stockings across the sand, flat-footed, like a child. Jane would never have done such a thing. I would not have done as much myself. I did admire her, I had to admit, whatever she was or was not.

I followed Flossie to the fringe of a strange, bedraggled crowd. Wet-looking, all of them, and sad, as if they’d been caught in a storm. A small, pale boy in faded dungarees and a woolly red sweater had picked up a stick and was prodding at something in the sand.

Don’t, Stevie, a woman, presumably the boy’s mother said; a bloated, equally pale, unpleasant-looking woman. She knocked the stick away. You don’t know what it is.

I’m not touching it, the boy said. Not with my hands.

No, for heaven’s sake, don’t touch it, someone else put in.

That’s right, keep well back, everyone.

What is it? Flossie said.

The strange crowd parted slightly to allow us to step closer. I stood behind Flossie, looking over her shoulder. A terrible smell wafted up, as of rot, soured flesh.

There, half-buried, lay what I at first thought to be an astonishingly large strand of kelp, bulbous and glossy and reeking. Sandflies hopped crazily upon its slick surface, the wet sand sticking to it there. Then I saw what it was, and my stomach lurched.

Is that … , Flossie began.

It’s a tentricle, said the boy, Stevie.

Tentacle, the mother corrected.

Is it an octopus?

Can’t be.

What then?

Beats me.

How long? Stevie asked.

Some fourteen feet, looks like, said a man in a battered homburg and spectacles. It was a moment before I noticed the glass in his spectacles was badly cracked on one side. I wondered if these were the “wharf rats” I’d heard about, who, having lost jobs and homes, lived in the abandoned canning shacks along the water or even, sometimes, beneath them. Certainly, they were a strange lot.

Impossible, said someone else.

Pace it out.

Not me.

I’m not going near it.

Look how it’s buried there at the fat end.

Like maybe it’s attached to something.

Oh, exclaimed the mother, awful. I can’t even think it.

The slick flesh of the thing looked sticky, purplish, as if it were bruised. The smell was dense, a sour reek of earth overturned. But it was the bloated thickness of the thing that disgusted me.

What are those big bumps? Along the bottom there?

Suckers, said the boy.

Steven!

Related: 40 Scariest Books of the Last 200 Years

That’s what they’re called.

I’m sure they aren’t, said the mother.

It’s what they use to grab onto things, said someone else, so they can move.

The mother put her hand to her mouth.

Has anyone tried to pull it out? Flossie asked.

Stevie stepped forward again, as if he might do so, and the mother swatted him back.

Arthor, Flossie said, turning to me, we should pull it out.

What? I said, appalled.

The crowd looked at me. I lowered my voice.

What on earth for?

Aren’t you curious?

Not enough to pull it out.

That’s a good idea, someone said. Somebody should pull it out.

But you don’t know what it’s got, the mother said.

You think it’s got something? Down there? asked a young woman, hardly more than a girl, in a bleached dress.

What? No. The mother paused then, frowning, considering this new possibility. She shook her head. No. What I meant is, you don’t know what it died from. I wouldn’t touch it, that’s all.

Maybe it isn’t even dead, someone observed.

Oh, it’s dead, all right. The smell.

Well, we won’t touch it, then, Flossie said. We’ll just dig it up a bit, won’t we, Arthor? Just to see.

Dig it up? I said in disbelief.

Again, the crowd turned to me. Stevie solemnly handed me his stick.

On the walk home, Flossie was quiet. The wind was up, ruthlessly, spitting cold drops that stung our eyes and faces, and we leaned into it, the sky black and rumbling over the water behind us. We walked quickly, in spite of Flossie’s heels. I made some silly joke about them, to lighten things, though I felt heavy also. She didn’t even bother to smile. The wind off the water buffeted against us, billowing her mackintosh out like a bright sail.

Better batten that down, sailor, I said, or you’ll float away.

“Still she said nothing, just wrapped her arms around herself, holding the coat to her waist, as if she thought I’d been serious.

Finally, I said, Does it bother you, that thing back there?

She shook her head.

Helen, then? Or are you worried … do you think … ?

I took her silence as confirmation. The image of my employer in the window of my attic room came back to me. The missing women. The boxes of clothing. I did not say it was troubling me, too. I pushed the thought away.

I want us to think well of each other, Arthor.

I do think well of you, Flossie. I told you.

I meant it. She nodded. After a few moments, she said, There’s another thing. That’s bothering me. Something I’ve been meaning to tell you.

I braced myself. Here it comes, I thought. The confession. She was, after all. Of course she was. It all made sense. Even as I told myself, It doesn’t matter; it doesn’t matter.

Related: The Scariest Books You've Ever Read

What is it?

The wind pasted her yellow curls across her eyes and she pushed them away and blinked furiously in the wind.

She said, I met the next-door neighbour this morning.

Next-door neighbour?

I can’t remember his name. He has a little dog. Maisy, or something. Daisy.

Puzzled, I recalled the hostile old man in the camel overcoat I’d seen in the lane.

What about him?

He said, she began, he said some funny things about you.

I looked at her in surprise.

What could he possibly have to say about me?

Well, I’d just been asking him, you know, about Helen. He said he’d seen her around but not in a few days, and I said I was worried, that she was supposed to be here and then she wasn’t, and I hadn’t heard anything from her.

What does that have to do with me?

That’s just it, Flossie said, looking uncomfortable. He said—oh, I shouldn’t even have brought it up. I wish I hadn’t.

What did he say?

He said … She gave an apologetic laugh. He said—it’s so ridiculous—he said, “If your friend’s gone missing, I’d look for answers with … ”

With what?

“That monster.”

Monster?

He said some funny things about you.

“The one who lives upstairs.”

She stared back at me, embarrassed, yes, but I could see a question there, too. It took me a moment. I stopped abruptly in the street.

What, me? You must be joking.

I know, crazy, isn’t it. I didn’t even know what to say.

You didn’t ask him what he meant by that?

No, she said, still hugging herself. Why should I?

I began walking and she followed. We’d crested the hill now by the university. The storm had cleared the lawns and quadrangles and paths of students. Elms twisted in the wind. Lights glowed in some of the classroom windows, as if it were evening. They flickered once, twice, and went out.

Oh, Flossie said. The lights …

Indeed, the sky had darkened ominously. I had darkened, too. What a day. And not half over.

Well, I said finally, stopping again, you might have at least, I don’t know, told him he was crazy. Or something.

A sudden gust of wind whipped her mackintosh open with a wet slap and I stepped away from her.

He is crazy, she said, wrestling the coat. Of course he is. I shouldn’t have told you. You’re not feeling well. I wasn’t thinking, I’m sorry. I shouldn’t have brought it up. She laid a hand on my overcoat sleeve. I thought we would just laugh about it. It’s all so silly. A monster. Imagine.

But she wasn’t laughing either.

So, all that talk, I said. Albert Fish. Jack the Ripper.

She took her hand off my sleeve.

No—

I began walking again and she hurried after me.

Arthor, of course not. You must believe me.

But I did not. I did not. She’d wondered about me. Neighbours talked about me. It built and built until my blood roared. I only wanted to be away from her. Away from my employer. Away from everyone. And there was nowhere, nowhere.

It wasn’t until we’d turned into the lane and the house, darkened, stood before us that it occurred to me, dreadfully. The realization stopped me cold.

It wasn’t me the old man was talking about. It couldn’t have been. Flossie only thought so because she didn’t know there was someone else.

I wasn’t the monster; it was my employer.

Want to keep reading? Download The Broken Hours today.

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Lineup to continue publishing the horror stories you love.

Featured image: The H.P. Lovecraft Wiki