Bestselling horror author Ania Ahlborn has long been known for crafting deeply unsettling stories that linger long after the final page.

From her breakout novel Brother to the chilling Seed and The Shuddering, Ahlborn’s work explores the darker corners of human emotion with cinematic flair and psychological depth.

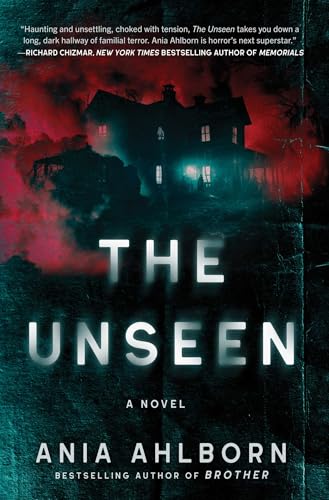

Her latest novel, The Unseen—out August 19th—may be her most haunting yet. Set in a remote Colorado farmhouse, the story follows Isla and Luke Hansen, a couple grappling with devastating loss, whose already fragile family begins to fracture when a mysterious, nonverbal child appears on their property.

As Isla becomes increasingly obsessed with the boy, strange and reality-bending events escalate, plunging the family into a nightmare that blurs the line between grief and horror.

We caught up with Ania Ahlborn to discuss the inspiration behind The Unseen, the emotional weight of writing about loss, and why creepy kids never get old.

Janelle Janson: What was the spark or initial idea that inspired The Unseen? Did Rowan’s character come first, or the theme of grief?

Ania Ahlborn: It started with grief. I mean, honestly, what doesn't? I didn’t set out to write a basic creepy-kid-comes-out-of-the-woods story. The Unseen is about pain that ruins your memory, your sleep, your body. The kind that shows up out of nowhere and pretends to be your kid.

Rowan was the first character I knew—the one that shaped the entire story—but he came after the theme. He’s a metaphor, an echo of the children Isla has lost. But he’s a wrong kind of grief, like if sorrow grew legs and called you Mommy.

JJ: Rowan is one of the most unsettling children in recent horror. What influenced his creation? Any real-life inspirations, legends, or archetypes?

AA: He’s not based on any one legend, though I’ve always been fascinated by changeling folklore and real-life stories of feral children. Both have that same uncanny almost-ness. Rowan taps into that. He’s not evil. He’s just… not correct in the way we, as a society, define “normal.”

And I don’t know if you’ve ever had a kid stare at you silently for five whole minutes without blinking, but it’s a horror movie. Children can be sleep-deprived goblins with no volume control and very questionable motives.

Rowan is just that—distilled and sharpened into something that’ll make your skin crawl.

JJ: The isolation in the story is palpable, despite there being seven family members. Was that contrast intentional?

AA: Absolutely. I think some of the loneliest moments in life happen when you're surrounded by people who are supposed to understand you and don't. The Hansens are all dealing with the same loss, but they’re each handling it differently.

And the fact that Isla isn't trying to pull the family together, and instead lets her grief bury her, is the real heart of the story.

She could have pivoted in the opposite direction. But she doesn’t. She looks at her life and sees not something good, but something lacking. And that perspective ends up being the family’s undoing.

JJ: Isla is a complicated, often unlikable character. What was your approach to writing her obsession and descent?

AA: I never intended to make Isla likable. I wanted her to feel real, because grief isn’t polite. It’s not graceful or sympathetic. Sometimes it curdles into obsession, and sometimes that obsession wears a mother’s face and tucks the kids into bed.

Isla’s descent isn’t sudden—it’s slow and quiet, the way most real-life unravelings are. She doesn’t wake up one day and lose it. She just stops resisting. Little by little, she hands herself over to the version of reality that hurts less, until that reality doesn’t look much like the truth anymore.

I’ve heard readers complain that a lot of my characters aren’t likable, but I’m not sure those particular readers are true horror connoisseurs. Likable characters are hard to find in this genre, especially if they reflect what it’s like to be a person with real emotions.

Likable characters belong in romantic comedies and children’s films, not in stories where grief eats you alive from the inside out.

JJ: Luke, by contrast, is more passive. How did you balance those two parental figures in shaping the emotional stakes?

AA: Luke’s passivity is a different kind of violence. He’s not storming through the house, breaking things. He’s just… not really present. He’s hard to pin down. He’s passive, but he’s not apathetic.

I think Luke represents fear—specifically, how fear can control us. Same as grief, right? But in his case, it’s a fear of confrontation. He’s afraid to step in and say, “This needs to stop,” because if he does, he might lose Isla completely.

Isla might be spiraling, but Luke’s silence is what gives that spiral room to grow. The real horror comes from watching two people fail each other in entirely different ways and realizing that both failures are fatal.

JJ: Each child in the Hansen family has their own voice. What was your process in crafting distinct perspectives, especially from younger characters?

AA: I love writing children, but writing from their point of view can be tricky. As the mother of a seven-year-old, I’ve seen firsthand how drastically a child’s worldview can shift.

My son at three, at five, and now at seven? Completely different people. If I wrote from each of those perspectives, I’d end up with three entirely different characters. And that was my approach.

I focused on age first—what each kid would care about, what they'd fear, what would feel big to them—and leaned into that.

But also, kids are weird little creatures with their own strange logic, and I wanted to honor that. They don’t talk like adults. They don’t think like adults. Their fears are different, their conclusions are often wildly wrong, and their inner monologues can swing from SpongeBob to death in three seconds flat. (Which, honestly, is part of the fun.)

That’s what I kept coming back to—that each Hansen kid needed to feel like they were living in their own version of reality. Because that’s how kids survive chaos. Some go quiet. Some act out. Some try to make sense of it the only way they know how—through stories and games and magical thinking.

I didn’t want them to feel like side characters in a horror movie. The kids in this book really tell the story best.

JJ: Grief plays a central role in the story but it’s layered with dread and speculative horror. Do you see emotional trauma as the ultimate horror?

AA: Absolutely. Isla doesn’t just wake up one day and suddenly fall apart. She’s already carrying baggage from her own childhood. A fractured, painful relationship with her mother has left her with no real blueprint for how to process loss—or even how to be a mother herself.

Up until now, she’s taken all of that pain and used it to fuel a desperate attempt to be a better mom. And she is a good mom… right up until the moment she isn’t.

Losing another child breaks something inside her. And this time, instead of healing, that fracture mutates. She becomes obsessive, unstable, and emotionally toxic. That wreckage is what opens the door to Rowan wreaking havoc on the Hansens. He might look like the horror, but he’s just the symptom. The real sickness is the emotional rot that’s been festering beneath the surface for years.

That’s what interests me most, and it’s a theme that comes up in my books again and again—not the monster under the bed, but the one sitting across from you at the dinner table.

JJ: The idea of welcoming the “unseen” or the unknown into the home is so unsettling. What does that concept mean to you personally?

AA: For me, the “unseen” is what slips in when no one’s paying attention, invited through grief, denial, and silence. Because, as we all know, emotional wounds—if left open long enough—start to fester. And when they do, something always finds a way to worm its way inside.

In The Unseen, that something is a strange, silent boy. But the real horror isn’t just that he exists—it’s that the family is too fractured to communicate their feelings to one another.

The adults are too preoccupied by their own emotions to perceive or even recognize the danger. The invitation is never spoken aloud, but it’s also never revoked.

It’s written in the things the Hansens don’t say to one another, and by the time anyone notices that, yeah, something is seriously off, it’s already too late. Rowan has already made himself at home.

That’s the kind of horror that gets under my skin. Not the thing outside, knocking—but the thing already inside, listening.

JJ: How did you decide on the Colorado setting? Did the rural isolation help shape the story’s tone?

AA: I grew up in the southwestern United States, and Colorado just felt right. It gave me the quiet I needed—the big skies and dry air. There’s a thin, breathless atmosphere out there that feels like it holds an electric charge. You’re always aware of how small you are in the middle of all that space.

JJ: You’ve written many different types of horror. How would you describe where The Unseen sits within your body of work?

AA: I honestly don’t know where this sits in my body of work. I just write whatever’s currently residing inside my brain… or festering might be the better word.

Everything I write is less about what’s in the woods and more about what’s under your skin. I rarely write anything that could be considered a slasher. I’m not particularly great at jump scares. There’s never a final girl.

My work tends to live in the realm of slow unravelings—in threats the characters let in themselves because it looks like hope instead of horror.

I’ve always loved horror that leaves you just a little emotionally wrecked. The kind that lingers long after the last page because some part of it felt uncomfortably true.

JJ: The ending left many readers shaken and with lingering questions. Did you always know how it would end?

AA: I mean, yes and no. It’s no secret that my books tend to have brutal endings, so I knew it wasn’t going to be pretty. I had a general sense of where it was headed—nowhere good—but the final few chapters formed organically.

I wanted everything to start folding in on itself. Interwoven in a way that, at a certain point, all you can think is Oh noand keep reading. It’s like a fuse that’s been lit, and you’re just waiting for the boom.

And of course, I never tie things up with a neat little bow. The Unseen is about damage that doesn’t go away just because the story ends.

JJ: Now that The Unseen is about to be released, what do you hope readers carry with them after finishing the final page?

AA: I hope they carry a sense of unease they can’t quite shake. That feeling like something’s just slightly off. Like maybe they left a door open. Like maybe they should go check on the kids, but not too closely.

This isn’t a comfort read. It’s for the folks who want the dread to linger. And if The Unseen sticks with readers not because of what jumped out, but because of what was always there, quietly waiting, I count that as a win.

Get your copy of The Unseen now!

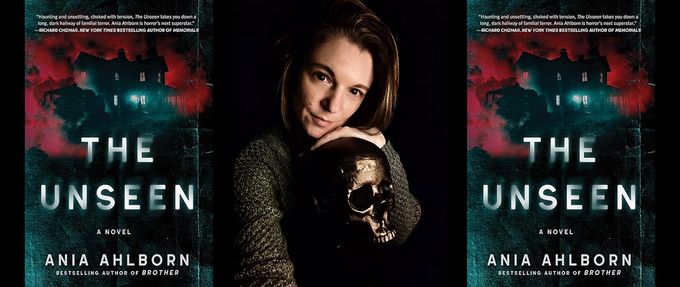

Featured photo: Aniaahlborn.com