In the turbulent years of the 1960s and 70s, few activists were as outspoken as Ira Einhorn.

Nicknamed "the Unicorn" after his last name (which means “One Horn” in German), Einhorn was a leading advocate for peace on the University of Pennsylvania campus, preaching the values of free love and advocating for environmental reform. But behind the hippie facade, darkness lurked.

In 1979, neighbors complained of a foul odor emanating from Einhorn's apartment. Police arrived and questioned Einhorn about his ex-girlfriend Holly Maddux, who had vanished without a trace two years prior. As they searched the apartment, they discovered a large black steamer trunk stuffed inside a boarded-up closet. What was inside would shock them all.

Related: Frozen with Fear: John Famalaro and the Horrific Murder of Denise Huber

Stored inside the trunk was Maddux's partially mummified body. Police quickly arrested Einhorn, yet Einhorn's twisted saga had only just begun. After his arrest, Einhorn claimed he was the target of a CIA cover-up. He leveraged the powerful connections he made during his activist years to make bail—whereupon he fled the United States and vanished into Europe.

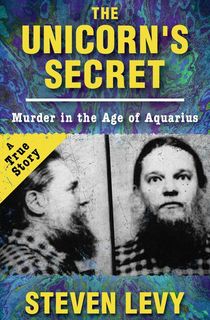

Prize-winning journalist Steven Levy draws on years of research, hundreds of interviews, and Einhorn’s and Maddux’s private journal entries to construct this absorbing narrative of an activist-turned-killer and murder in the age of peace and love. His book served as the basis for 1999 NBC television miniseries, The Hunt for the Unicorn Killer, starring Naomi Watts and Kevin Anderson.

Read on for an excerpt.

Wednesday, March 28, 1979, would have been an eventful day for Ira Einhorn in any case. At around 4:00 A.M., while Ira was reading, radiation began leaking into the atmosphere near a nuclear plant 100 miles to the west of Philadelphia. The plant was named Three Mile Island. Ira Einhorn’s prediction a few days earlier of the nuclear issue heating up had been fulfilled sooner than he had expected. In normal circumstances, Einhorn would have been on top of the crisis.

As a figure in the environmentalist movement, he might have even assumed an active role in the media circus that would assemble in Harrisburg over the next few days.

But Ira Einhorn was destined to make headlines of his own.

Related: 8 True Crime Books About Bizarre Murders That You Might Not Know About

The Unicorn was still sleeping when Detective Michael Chitwood rang the outside buzzer of 3411 Race Street on the morning of March 28. It was approximately 10 minutes before 9:00. Ira Einhorn grabbed a robe and pressed the button that unlocked the outside door. Chitwood, accompanied by six other police officials, opened the door and began climbing the steps. Before the detective reached the door, Einhorn had opened it. Ira had not bothered to fully cover himself with the robe. It was then that Chitwood identified himself as a homicide detective, and told Ira that he had a search-and-seizure warrant for his house. Michael Chitwood, a tall wiry man in his 30s, was smiling. Einhorn laughed. “Search what?” he asked.

What could the Unicorn have to hide?

Chitwood told him to read the warrant. He handed Einhorn the 35-page document, signed the night before by a Philadelphia municipal court judge, granting permission for the police to search his apartment for any evidence relating to the disappearance of one Helen (Holly) Maddux, age thirty-one.

Holly was the woman Ira had lived with on and off since 1972. A blond Texas-born beauty, she was shy and waiflike—people who described her always seemed to light on words like delicate and ethereal. Ira had not seen her since September 1977, when, he told his friends, she went out to do some shopping at the nearby food coop and did not return. Ira said something to this effect to the policemen invading his sanctum.

Victim Holly Maddux.

Photo Credit: MurderpediaChitwood led his crew inside. There were three men from the Philadelphia Mobile Crime Detection Unit, two police chemists, and the captain of the Homicide division. Some of the men were carrying tools—power saws, hacksaws, and crowbars. Others had photo and sketching equipment. It was quite a crowd for the small apartment.

“Can I get dressed?” Ira asked.

“Certainly,” said Detective Chitwood.

It only took a few seconds for Einhorn to throw on jeans and a shirt. He was still tired from being suddenly wakened, but he prided himself on his excellent control in stressful situations. A few days later he would explain his behavior to a reporter:

My reaction was, what is this all about. And of course, I have very good control of myself. I immediately gave myself an autohypnotic command—just … cool it. Cool it and watch this as carefully as possible, which is what I did. Which to them translated into as my being nonchalant, but I was just being totally observant. Because I’ve been through [tough situations], I’ve faced guns, I’ve faced the whole thing. So if you don’t act quickly, you can make a mess. I was not about to do anything. So I observed, literally, when they marched to the closet on the back porch.

Related: The Woman Who Was Bludgeoned By a Claw Hammer—And Survived

Almost as if Chitwood had no interest in the apartment itself—though in fact he had never seen a place with so many books, and it held a strange fascination for him—he brushed aside the maroon blanket covering the French door on the north end of the apartment and opened it to the enclosed porch overlooking the backyard of 3411 Race Street. The porch was a narrow space, less than 7 feet wide, extending back 13 feet. The floor was slightly sloped. The floorboards were painted for a striped effect, every other one blue or white. There were windows on the north and west walls. On the east wall was a closet that took up a decent chunk of the porch.

Chitwood had walked purposefully to that closet. Now he stopped, contemplating the thick Master padlock on the closet door.

Chitwood asked Einhorn if he had a key to the closet. Einhorn said he didn’t know where the key was. “Well, I’m going to have to break it,” said the detective.

“Well, you’re going to have to break it,” Einhorn echoed.

Mike Chitwood planned to follow strict procedure on this case. He did not want to make a mistake that might invalidate any evidence that might later be presented in court. He also wanted to create documentary proof that his search was being carried out legally. Thus the photographers from the Mobile Crime Detection Unit. Chitwood instructed one of the crime unit men to take a picture of the locked door. Photograph. Then, he took a crowbar and broke the lock. Another photograph.

The closet was 4½ feet wide, 8 feet high, and a little less than 3 feet deep. There were two foot-wide shelves that were crammed with cardboard boxes, bags, shoes, and other paraphernalia. Some of the boxes were marked “Maddux.” On the floor of the closet was a green suitcase. On the handle was the name “Holly Maddux” and a Texas address.

Behind the suitcase on the closet floor was a large black steamer trunk.

Chitwood began removing items from the closet, first having them photographed, then examining them and handing them back to the others for closer examination and cataloging. The boxes contained items such as kitchenware, clothing, schoolbooks, and papers. The suitcase also had women’s clothing in it, and four or five letters. They were addressed to Holly Maddux, and their postmarks indicated they were more than two years old.

Related: The Best True Crime Books You’ve Ever Read

Chitwood opened a handbag he found in a box sitting on the trunk. Inside the handbag was a driver’s license and social security card; they bore the name “Holly Maddux.”

Chitwood began to notice a faint but unpleasant odor. He continued to remove boxes from the closet. Ira Einhorn, who had been shuttling between the main room and the porch while all this was going on, was now standing by the doorway again.

Chitwood thought that he could sense the fear rising in Einhorn at that point. But Ira Einhorn would claim that he was almost in a meditative state. He would say he suspected that this intrusion was somehow connected to his efforts to disseminate crucial information about highly charged subjects like psychotronic weaponry. Perhaps the police were working in concert with intelligence agencies. As a student of the Kennedy assassination, Einhorn understood that anything was possible. At a conference in Harvard last year, Einhorn and his colleagues had discussed the riskiness of their crusade. “What we are trying to do,” Ira had noted, “is change the reality structure that we’re living in—of course the CIA is going to be after us.” They must not be foolhardy, he warned, but they must continue with their work. If Ira was to be killed, so be it—but he was not going to let fear prevent him from doing what he thought was correct.

Was this search now the result? Only a few weeks before, Ira had gotten a letter from a close friend warning that the FBI was spreading rumors that he had murdered Holly. Ira would later say that the that the letter flashed through his mind as he stood, still groggy from exhaustion, surrounded by these strange and unfriendly men.

Michael Chitwood took off his suit jacket. He was now ready to open the trunk.

The black steamer trunk had been resting on a filthy, old, folded-up carpet that seemed jammed underneath to compensate for the slope of the porch floor. The trunk was 4½ feet long, 2½ feet wide, and 2½ feet deep. Chitwood opened the two side latches, but the hasp-type latch in the middle was locked. He asked Einhorn for the key. Again, Einhorn said he didn’t have one. So Chitwood took the crowbar and broke the lock. Photograph. He opened the trunk. The foul odor Chitwood noticed was now much stronger. Now Chitwood was sure he knew what that odor was.

“Hey,” said Mike Chitwood to one of the Mobile Crime men, “get me a pair of gloves.”

Chitwood put on the clear rubber gloves and went back to the open trunk. On top were some newspapers. Photograph. Chitwood looked at the papers before he lifted them out. Some were from the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin dated September 15, 1977. Others were part of the New York Times Book Review of August 7, 1977. Underneath the newspapers was a layer of styrofoam packing material. It looked to Chitwood like stuff you’d find inside a pillow. He could also see some compressed plastic bags with a Sears label.

Related: How a Journalist Got Inside the Mind of Killer Marie Hilley

Chitwood moved back to the trunk. Beginning on the left-hand side of the trunk, he slowly scooped the foam aside. After three scoops, he saw something. At first he could not make out what it was, because it was so wrinkled and tough. But then he saw the shape of it—wrist, palm, and five fingers, curled and frozen in their stillness. It was a human hand, and now there was no doubt in Mike Chitwood’s mind about the contents of this trunk. He dug just a little deeper following the shriveled, rawhidelike hand, down the wrist, saw an arm, still clothed in a plaid flannel shirt. And he had seen enough.

Chitwood backed away from the trunk. He removed the rubber gloves. He told one of the men to call the medical examiner. He headed to the kitchen to wash his hands. Then he turned to Ira Einhorn, who was still maintaining his studied nonchalance. “We found the body. It looks like Holly’s body,” he said.

“You found what you found,” said the Unicorn.

Want to keep reading? Download The Unicorn’s Secret.

Featured photo: Murderpedia