In the early morning hours of April 28, 1908, a fire reddened the sky over La Porte, Indiana. The source of the alarming light? Belle Gunness’s farmhouse, engulfed in flames.

Neighbors rushed to the scene of the blaze; Gunness had three children and the sleeping family was most likely trapped inside. Yet despite the neighbors’ efforts to break through the locked doors or arouse someone—anyone—from within the burning structure, no one stirred. The farmhouse burned to the ground.

Afterwards, authorities dug through the rubble in search of victims. They soon found four bodies, arranged in a row on the basement floor. Three of the bodies belonged to Gunness’s children: Myrtle (eleven), Lucy (nine), and Philip (five). The fourth body, an adult woman’s, was presumably Gunness herself. But there was a problem: The corpse was missing its head.

News of the fire spread throughout the community. Ray Lamphere, a former farmhand and ex-lover of Gunness’s, was arrested under suspicion of murdering the family and then igniting the blaze. Meanwhile, authorities continued to sift through the charred wreckage of the Gunness farmhouse. The head was still missing. Where could it be? Workers expanded their search beyond the farmhouse’s foundation to a nearby hog pen—and unearthed a grisly scene beyond their darkest imagining.

Buried in the dirt were hacked apart human remains. Further digging turned up additional remains; authorities eventually recovered at least eleven bodies scattered across the property. Belle Gunness, who previously had been viewed in a tragic light, was now believed to be a serial murderer who claimed a staggering number of lives.

Who Was Belle Gunness?

Belle Gunness was born in 1859 on the shore of Lake Selbu in northern Norway. Little is known of her early life. She emigrated to the United States around 1881, and settled in Chicago where she married a man named Mads Albert Sorenson. What followed was a series of fires and sudden deaths that seemed to benefit Belle’s financial standing. First, the candy store she ran with her husband burned to the ground. Then, in 1900, Mads himself died on the one day his insurance policies overlapped, thus making his death worth twice as much. Belle used the life insurance money to purchase a sprawling property in La Porte, Indiana.

Not long after her arrival, she married her second husband, Peter Gunness. While the last name stuck, Peter was not long for this world. He died in 1902, after a meat grinder purportedly crashed down upon his head. The twice-widowed Belle Gunness set about running her farm on her own terms, hiring farmhands like Ray Lamphere to assist with her needs. Gunness also began placing personal ads in Norwegian-language newspapers, aimed at attracting a “good and reliable” man to come join her on her farm. Of course, “some little cash is required for which will be furnished first-class security.”

As we now know, the lonely heart ads were a trap; many of the suitors who answered Gunness’s call journeyed to their deaths.

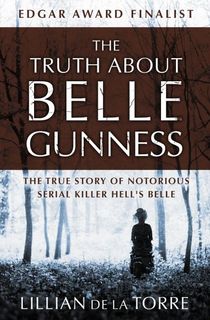

In The Truth About Belle Gunness: The True Story of Notorious Serial Killer Hell’s Belle, Lillian de la Torre delivers the shocking true story of the woman who led a secret life as a serial killer in the early 20th-century Midwest. An Edgar Award finalist for best factual crime story, The Truth About Belle Gunness is a “magnificent [and] brilliantly written” (New York Times) exploration of a highly unusual murderer—perfect for fans of Devil in the White City and In Cold Blood.

In the excerpt below, de la Torre examines the methods Gunness used to lure multiple men to their doom, and the growing speculation that she didn’t die in the house fire but faked her own death to escape justice.

Read on for an excerpt of The Truth About Belle Gunness: The True Story of Notorious Serial Killer Hell’s Belle.

There was a widespread burning interest in “the Gunness system” of matrimonial bait. The federal government turned a severe eye on courtship by mail, and the press published everything it could dig up on the subject. From the editor of Skandinaven, a Norwegian-language paper, newsmen extracted the text of Belle’s last ad. The indefatigable woman had opened a new campaign in March, 1908, announcing to the world:

WANTED—A WOMAN WHO owns a beautifully located and valuable farm in first class condition, wants a good and reliable man as partner in the same. Some little cash is required for which will be furnished first-class security.

This no-nonsense appeal was designed to fetch good solid farmers, and it fetched them. A Mr. Carl Peterson had been attracted. When the Gunness system became front-page news, he came forward with the come-on letter that Belle had written to him. It was dated April 14, 1908, just two weeks before the fire, and it told him crisply:

There have been other answers to the same advertisement. As many as fifty have been received. I have picked out the most respectable, and I have decided that yours is such.

My idea is to take a partner to whom I can trust everything and as we have no acquaintance ourselves I have decided that every applicant I have considered favorably must make a satisfactory deposit of cash or security. I think that is the best way for parties to keep away grafters who are always looking for such opportunities, as I have had experience with them, as I can prove.

Now if you think that you are able some way to put up $1,000 cash, we can talk matters over personally. If you cannot, is it worth while to consider? I would not care for you as a hired man, as I am tired of that and need a little rest in my home and near my children. I will close for this time.

With friendly regards,

MRS. P. S. GUNNESS

Mr. Peterson was lucky. He did not have $1,000.

Belle Gunness and her three children

Photo Credit: MurderpediaStill luckier, in his own opinion, was Mr. George Anderson of Tarkio, Missouri. He had answered an earlier ad, he told the press, liked the lady’s replies, and decided to go to La Porte and look things over.

On the second day of his visit, Mrs. Gunness asked him point-blank how much money he had. He had only $300, but he had a big farm in Missouri. Belle told him to go home and sell it and come back with the cash.

That night, in the small hours, Mr. Anderson woke with a start. Mrs. Gunness was bending over his bed. When he spoke, she ran out.

Mr. Anderson took fright. On the instant he dressed and ran away. Perhaps because he felt he had made a fool of himself, he told nobody of his alarming adventure.

Some people wondered if he should have been so very much alarmed. Ole Budsberg, they pointed out, had been perfectly safe at Belle’s—until he went home and sold out.

Related: Belle Gunness: The Black Widow of the Midwest Who Lured Numerous Victims to Their Deaths

Then what was Belle after? Did she bring her suitors love before she brought them death? Was that the charm she used to make grown men willingly give up to her every cent they had?

Thinking of the hog lot, Mr. Anderson was still shuddering over his narrow escape. He recalled how Myrtle had looked at him as on a doomed man. “She would eye me with a pitiful look,” he recalled, “and when I glanced at her during a meal she would turn white as a sheet.”

Frank Riedinger of Delafield, Wisconsin, also went to visit Mrs. Gunness. A letter came back, not in his handwriting, to say he had decided to “go West.” When the hog lot gave up its secrets, those he left behind too quickly lost hope and sold him out. Riedinger, who had in fact left La Porte in one piece, had to sue before he could convince them that he was alive and could claim his possessions.

Want more true crime books? Sign up for The Lineup’s newsletter, and get our recommended reads delivered straight to your inbox.

People all over the country were convinced that missing relatives had ended up in the hog lot. Sheriff Smutzer was pestered to death about it. When a wayward girl eloped, when a henpecked husband deserted his wife, the first thing the bereaved thought of was the Gunness farm. Inquiries poured in. Some were foolish. Others made sense. At least ten other Norwegian men, the inquiries showed, had taken their savings and gone off to La Porte, never to return. Were their bones still buried somewhere on the farm? If Smutzer kept notes on disappearing fellows that he really ought to dig for, they must have read something like this:

George Berry left home in July, 1905, saying he was going “to work for Mrs. Gunness.” He had $1,500. Provisionally identified as the second body in Gurholt’s grave in the hog lot.

Herman Konitzer took $5,000 and left home “to marry a wealthy widow in La Porte” in January, 1906. Posted one letter from La Porte.

Christian Hinkley, Chetek, Wisconsin, in the spring of 1906 sold his farm for $2,000 and left. Changed his Decorah Posten subscription to La Porte. La Porte post office testified that Mrs. Gunness received mail as Mrs. Hinkley.

Olaf Jensen, 23, Norwegian, in May, 1906, wrote to his mother in Norway that he had reflected on a matrimonial ad in Skandinaven and decided to marry the lady, a widow from Norway who lived in La Porte. Went down for a visit, returned home to turn his belongings into cash, and went back to La Porte. Never seen since.

Charles Neiburg, 28, left Philadelphia in June, 1906, saying that he was going to marry Mrs. Gunness. Took $500 in cash with him. Had a hobby of answering matrimonial ads.

Abraham Phillips, Belington, West Virginia, told relatives he was leaving to marry a rich widow in Indiana. Had a big roll of bills, a diamond ring, a Railway Trainmen badge. Disappeared in February, 1907. A railroad watch turned up in the ashes of the Gunness house.

The bodies were found in Gunness' home when it burnt to the ground.

Photo Credit: MurderpediaTonnes Peter Lien saw an ad, sold his farm, and left Rushford, Minnesota, for La Porte to marry Mrs. Gunness His brother reported that he helped to sew $1,000 in bills in the sleeve of Tonnes Peter’s coat, and asked if a heavy silver watch initialed “P. L.” had been found. It had. Since Lien left home April 2, 1907, and all burials about that time were accounted for, his body had not been found.

E. J. Thiefland of Minneapolis sought by a private detective. Described as a tall man with a sandy mustache. Saw an ad in a Minneapolis paper on August 8, 1906. Corresponded with Mrs. Gunness. On April 27, 1907, wrote to his sister saying he was going down to La Porte “to see if this lady is on the square.” Never heard of since.

Emil Tell took $5,000 in May, 1907, and left Osage City, Kansas, to marry a rich widow in La Porte. Q. Was he the man with the pointed beard seen at the Gunness place in June, 1907?

John E. Bunter of McKeesport, Pennsylvania, fifty-two, light gray hair, left saying he planned to marry a widow in Indiana. Went away on November 25, 1907. Q. Did he accompany Mrs. Gunness into Oberreich’s in December to buy a wedding ring?

S. B. Smith missing. Ring initialed S. B. found in ruins.

Paul Ames disappeared. Initials P. A. on ring found in ashes ...

Sheriff Smutzer soon admitted there had to be more digging. By fits and starts more digging went on. In a disused privy vault they found a detached head of a woman with long blonde hair. They never found the woman’s body that went with it, and they never found out who the woman might be. They never found the man’s head that was missing from Gurholt’s grave.

Ray Lamphere

Photo Credit: MurderpediaThey dug up an old well, and a soft spot under a lilac bush, and the dirt floor of the cellar, and some more spots in the hog lot. On that seventy-acre farm they passed over the old vineyard by the tracks, the rye field, and the ground covered by the removed barn and the cemented floor of the shed.

Once, looking very sporty in his leather cap and turtle-neck jersey, Sheriff Smutzer brought a pack of foxhounds out to the farm. The hounds ranged about sniffing. They found six places interesting enough to prompt a good deal of whining and scratching. The places were marked for digging; but if they were dug, nothing turned up.

Then one day the hogs rooted out some bones that looked like arm and leg bones; but by that time the authorities were tired of bones.

What was the use? Suppose they did find more bodies; how would that advance the matter in hand—the case against Ray Lamphere? Money was short, Mrs. Gunness was gone, and the Sheriff’s office was being pestered every day with every kind of nonsensical demand.

Nuts anonymous, nuts self-advertising peppered the Sheriff and the prosecutor relentlessly with every species of lunacy. Crank letters threatened and taunted: “Ha! Ha!! Ha!!! Wise Heads, You, Nit. From One Who Knows.” Persons in touch with the Infinite claimed to be in touch with Belle in the beyond, or offered to get in touch with her for a consideration. One seer offered to identify the unknown victims, if he could be provided with some bones. He received some from the butcher shop.

The worst pests, to those who were getting ready to prosecute Ray Lamphere for murdering Belle Gunness, were the people who insisted on reporting that they had seen Mrs. Gunness, in the flesh, since the fire. With public opinion in that state, the prosecutor would have a tough time getting a conviction.

MRS. GUNNESS VERY NUMEROUS, headlined the Herald. The vanishing ogress was turning up all over. She was “seen” in every one of the forty-eight states, Canada, and Mexico. She was “located” on an ocean liner, in an upper berth in Texas, in a Chicago streetcar. She was “arrested” on a New York train. The victim of that arrest was so insulted that she sued the railroad for $30,000.

Excited people deluged Smutzer with letters on the subject, demanding $5,000 reward or enclosing “50¢ for your trouble,” as their natures dictated. A farmer in Illinois wrote that he had a suspect locked up in his granary. The exasperated authorities had thrown away his address before it occurred to them that somebody ought to go and let her out.

Elsewhere the absconding murderess turned up “mysteriously veiled,” or with her teeth covered with chewing gum, or muffled in wraps and transported by stretcher, or publicly changing disguises by the railroad tracks. In July, trusting to two veils, a black one and a white one, she had the effrontery to show up by daylight at the scene of her crimes. […]

Belle Gunness's property in La Porte, Indiana.

Photo Credit: MurderpediaIt was exasperating to Wirt Worden to see Smutzer spending time and money in an attempt to put Ray Lamphere in the death cell, while he refused to spend a day or a dollar looking for Belle Gunness. The defending lawyer was seriously convinced that Belle Gunness was alive somewhere, laughing at them all, and would have the last laugh unless they sought her in earnest. But there was not enough money in his pocket, or even in the county treasury, to follow up every lead. An influential county commissioner managed to get an official $4,000 reward posted for Belle’s capture, and a gentleman from Kansas started a private reward fund by forwarding $1 in cash. But what was the use of a reward of $4001 if the authorities would not move? Now and then Worden managed to needle them into action; but every false lead made them harder to needle.

Some leads were very pointed, like the anonymous letter that came to Prosecutor Smith:

The body of the woman found in the ruins is a cadaver murdered by Mrs. Gunness, who decapitated her and put her [Mrs. Gunness’] rings on her fingers. She had two persons to help her and one of them drove her to Valparaiso early in the night, where she boarded a Pennsylvania train for New York City. The other was Ray Lamphere, who fired her house early in the morning. They both got $1,000. Mrs. Gunness is now posing as a man.…

Yours,

TRAVELING MAN

Who could the first accomplice be? A letter came, Worden announced, with a name in it; but it was a name too hot to publish. The Herald reported:

The letter charges that a certain man, who is said to live not far from La Porte and who is declared to be quite well-known, was an accomplice of Mrs. Gunness. The name of this person is not disclosed, because it would not be right to drag him into the case if he is an innocent party. The matter is being fully investigated, but no steps will be taken to arrest him unless it is found that he really has information of value in his possession.

Was it the same name as the one the pool-hall louts bandied about? Was it the name that had been heard in whispers even before the hog-lot discoveries made the case notorious? Were Ray’s partisans trying to scare somebody into making a break?

If so, it didn’t work. The owner of the name was too well entrenched to scare easily. Safety lay in sitting tight. He sat tight.

It was a long sit. Ray Lamphere sat it out in the county jail. He sat out the summer and he sat out the early fall. He sat out the wild search for Mrs. Gunness, and the serious building up of the case against himself for murdering her.

Want to keep reading? Download The Truth About Belle Gunness: The True Story of Notorious Serial Killer Hell’s Belle.

Want more true crime books? Sign up for The Lineup’s newsletter, and get our recommended reads delivered straight to your inbox.

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Lineup to continue publishing the true crime and creepy stories you love.

Featured photo: Alchetron