In the mid-1980s, three prominent families were swept up in a wave of violence known as the Bitter Blood murders. Pride, paranoia, obsession, and savage revenge brought about the horrific deaths of 9 people in Kentucky and North Carolina. But what connected these three doomed families? Marriage.

The first deaths occurred in the summer of 1984. The bodies of 68-year-old Delores Lynch and her daughter, 39-year-old Janie, were discovered in Prospect, Kentucky on July 24th. Shot multiple times, it seemed as if the murders were a result of a professional killer.

Related: Unsung Horrors: 10 Underrated True Crime Books

When Tom Lynch—the son of Delores and brother of Janie—learned the tragic news of his family’s slaughter, he was with his two young sons. Tom rarely got to see his children, the result of an acrimonious split from his former wife, Susie Newsom Lynch. Susie was combative; she had never gotten along with Tom's mother—in fact, Susie and Delores had fought on Susie and Tom's wedding day.

So when, in the early summer of 1985, nearly a year after the deaths of Delores and Janie, members of Susie’s own family met a similarly brutal end, it arose the suspicion of the police.

On May 19th, 1985, authorities discovered the bodies of 65-year-old Robert W. Newsom, 66-year-old Florence Sharp Newsom, and 84-year-old Hattie Newsom at Hattie Newsom's home. The father, mother, and grandmother of Susie Newsom Lynch were murdered in a similar fashion to the Lynch family victims. However, these deaths bore the markings of far greater violence.

While police suspected that Susie had a hand in the deaths, their eye was on another suspect: Fritz Klenner. Fritz had a close connection to the Newsoms—he was Susie’s first cousin, the son of Florence’s sister, Annie Hill Sharp Klenner. Susie was seven years older than Fritz; growing up, the two were not particularly close. This changed in later years. As adults, Susie and Fritz became intimate.

Like Susie, Fritz Klenner was a troubled individual. Spurred by the demands of an overbearing father and an inflated sense of self-importance, he was also a pathological liar. He set up a fraudulent medical practice, treating patients without any degree or license. He wove tales of valiantly saving his father’s life, fighting as a Green Beret during the Vietnam War, and working undercover for the CIA. Every word was a lie.

It was through these lies that Fritz embarked on a mission of violence that touched all three families. Fritz enlisted the help of a young and impressionable neighbor named Ian Perkins. He told Ian that he needed aid in a CIA mission to wipe out drug traffickers, and if Ian performed well enough, he might be considered for a more serious role in government intelligence. On the night of the grisly Newsom murders, Ian drove Fritz Klenner to Hattie Newsom's home and served as the getaway driver, still under the assumption that he was part of a CIA mission.

Related: 10 Shocking True Crime Books About Murderous Families

Ian quickly folded under police pressure, and the truth was soon laid out before him. Weighed upon by guilt, he agreed to wear a wire and try to capture a confession from Fritz. On June 3rd, Ian Perkins climbed into Fritz Klenner's car and recorded a statement vaguely implicating the man’s guilt. It was the closest anyone would ever get to a full-blooded confession in the Bitter Blood murders.

Mere hours later, the violence came to a fiery end. Police descended on Fritz’s Greensboro apartment with the intent of arresting him. But Fritz fired back at the police, then climbed into his SUV and fled the scene with Susie in the passenger seat and Susie's two sons in the back.

A pursuit commenced. Fritz was both wild and unafraid. He opened fire upon police officers with an Uzi. After escaping a police barricade, he drove further down the road and then came to a stop. Then the SUV burst into flames.

The car was wired with explosives.

Susie died in the explosion. 10-year-old John and 9-year-old Jim Lynch were also dead—though forensic examiners later learned that the boys had been poisoned with cyanide and shot in their heads prior to the detonation. Fritz initially survived the blast, only to die on the road from internal hemorrhaging.

Related: 46 Gripping True Crime Books from the Last 54 Years

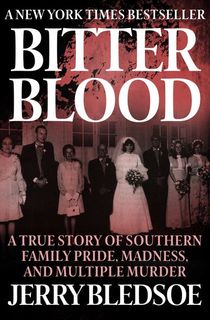

What caused such a senseless wave of death? Was Fritz the man who pulled the trigger in the family slayings or did someone else carry out the deed? And just how much did Susie know? The terrifying and scandalous truth is revealed in Jerry Bledsoe’s bestselling true crime novel, Bitter Blood.

Bledsoe’s book on the Bitter Blood murders brilliantly details the shocking twists and turns that claimed the lives of nine people, including Susie Newsom Lynch, Fritz Klenner, and Susie's two children. A #1 New York Times bestseller when it was first published, Bitter Blood is “an engrossing southern gothic sure to delight fans of the true-crime genre" that vividly recreates one of the most shocking crimes in recent memory (The Charlotte Observer).

In the compelling excerpt below, Bledsoe recreates the scene of the Newsom murders through the eyes of Detective Allen Gentry.

Read on for an excerpt of Bitter Blood, and then download the book!

Allen Gentry didn’t have to search for the house. He topped the hill and saw police cars everywhere. Rarely had he seen so many at a crime scene. He parked on the opposite side of the street a short distance from the house and walked to the driveway. The confusion that had reigned earlier had subsided, and the house had been sealed off by Winston-Salem police. Two patrolmen were guarding the foot of the driveway, where rescue squad members and several bystanders also had gathered. Gentry saw his lieutenant, Earl B. Hiatt, usually called EB, arriving and waited for him. The two walked up the driveway, where they were greeted by Larry Gordon, the first deputy to reach the scene. Any thought Gentry had of a case easily cleared was dispelled when Gordon told them that three bodies were in the house, two women and a man, all shot several times, and no weapon in sight. He read the names of the victims from a pad, but neither Gentry nor Hiatt had heard of the Newsoms. Gordon explained that jurisdiction was in question, and Hiatt and Gentry agreed they should proceed on the assumption that this was their case. More specifically, Gentry knew, the responsibility likely would fall on him.

“Well, let’s see what we’ve got,” he said, heading for the back door of the Newsom house.

To the right, just inside the back door, a short hallway with rose-adorned wallpaper led to the living room, foyer, and staircase. There Bob Newsom’s tall, slender body lay on its right side in a near-fetal position. He was wearing blue jeans; a green, blue, and lavender plaid flannel shirt with long sleeves; and black corduroy house slippers with no socks. He had been shot three times in the abdomen, once in the right forearm (the only close shot), and once in the back of the head. He was just outside the arched entrance to the living room, and it appeared that he had been trying to flee when fatally wounded.

Related: Marriage, Madness, and Murder Collide in Final Vows

On the drop-leaf cherry table in front of which Bob’s body lay was a large antique hurricane lamp with a rose-colored globe that was a particular treasure of his mother. Once the lamp had had a twin, but Debbie Miller, Nanna and Paw-Paw’s youngest grandchild, kicked and broke it while sliding down the banister as a child, a memorable experience to the family because it marked the only time anybody ever saw Nanna angry at one of her grandchildren. A tall grandfather clock, one of Paw-Paw’s most prized possessions, stood near Bob’s head, and on the floor beside the clock, where it had been placed to wait out the renovation of the house, was a wood-framed table clock with a .45-caliber bullet casing on top. Only six inches from Bob’s feet, in front of a small table with its single drawer pulled out, another orphan of the remodeling, a hole thirty inches in diameter had burned through the olive green carpet, charring the floorboards underneath. Inside the circle were ashes and odd bits of scorched paper, some from an organic gardening magazine that apparently had supplied fuel for the fire. Florence’s pocketbook lay beside Bob’s body, its contents dumped onto the carpet.

In the living room, a large mirror over the fireplace at the end of the room opposite the archway reflected a macabre scene of disorder. A wooden rocking chair lay on its side between the flickering console TV, tuned to a High Point station, and the door to the breezeway where Nanna had set up her temporary kitchen. A set of fireplace tools had been overturned. A green recliner near the fireplace was in the full rest position, and beside it, neatly aligned, were Florence’s shoes. A bunch of red grapes lay on a Fortune magazine by a Winston-Salem telephone directory on a marble-topped table next to the chair. On the telephone directory was a green plastic supermarket vegetable tray with raw cut cauliflower on it. A full can of spray starch stood on the coffee table.

Florence’s thin body lay in a grotesque sprawl in front of the TV in a pool of dried blood. She was wearing a white skirt and a light blue-and-white striped knit top. Although investigators would not notice it immediately, her throat had been slit, a deep, two-inch gash just above the glasses that hung around her neck on a decorative chain. She had two shallow stab wounds in the right side of her neck, a third in her right shoulder. More prominent were three deep stab wounds that penetrated her back. One, it later was discovered, had severed her aorta. A single shot in the right side of her chest had penetrated her liver, heart, and both lungs. She also had been shot in her left temple as she lay on the floor, the bullet passing through and lodging beneath her. Her wedding band was bent, the finger under the ring cut and broken, as if somebody had tried unsuccessfully to remove the ring. Her engagement ring, with its three-quarter-carat diamond, was gone.

Related: A Dark and Bloody Ground: Sherry and Benny Lee Hodge’s Deadly Kentucky Rampage

Nanna, who had grown a bit plump in her later years, had been shot three times. One bullet, apparently a wild shot, had grazed the left side of her head. A second hit her in the lower right side. The fatal shot struck her right temple, passed through her head, and lodged in her shoulder. She lay on the sofa with hands clasped beneath her chin, and many police officers who saw her were convinced that she had been praying when she was shot, although later evidence showed that she had been placed in that position after being shot. On the wall above her head, near two bullet holes in the plaster, was a framed antique needlepoint quote from Joshua: “As for me and my house, we will serve the Lord.”

A floral-patterned blue-and-green easy chair near the archway had been pierced by a bullet that also went through one corner of an ornate étagère and ended up in the wall. Another bullet passed through the archway, struck a piece of molding on the far side of the staircase, and plopped back onto the steps. From the angle of the shots, most appeared to have been fired from near the breezeway door.

In a clear glass dish on the étagère, easily visible, was a small wad of currency—four one-hundred-dollar bills, a fifty, four twenties, a ten, and a one. Propped next to the dish was a North Carolina Department of Revenue income tax refund check for $661.26. In Nanna’s bedroom, on the other side of the hallway, drawers had been pulled from a chest and stacked on the floor. A heavy gold-and-pearl bracelet worth thousands of dollars lay on the floor near the foot of the bed. More drawers were stacked in an upstairs bedroom that Nanna once had used, a bedroom decorated with photographs of important events in the lives of her two children and five grandchildren. In another upstairs bedroom, the one Bob and Florence used every weekend, Bob’s briefcase lay open on the floor by an antique washstand. On the stand was a china urn hand-painted with roses. Paw-Paw had brought the urn home one day wrapped as a gift for Nanna.

“What in the world am I supposed to do with that?” she had asked on opening it.

“Well, I don’t know,” he’d replied with a grin, “but I’ll bet you’ve got the prettiest chamber pot of any woman in Forsyth County.”

The briefcase was empty except for a calculator and some pens.

His walk-through of the house convinced Allen Gentry that this was not going to be an easily solved case. For one thing, the trail was cold. The murders obviously had occurred hours earlier, maybe a day or more. And what was the motive? Clearly, this was no typical robbery. What robber would leave behind plainly visible cash and expensive jewelry? The murders looked like executions to him.

Related: When Murder Runs in the Family: Frances Schreuder and the Killing of Franklin Bradshaw

Several things about the scene were puzzling to Gentry. Why was the storm door broken, while a key was left in the back door lock? Had one of the victims been surprised by the murderer while entering the house? Why was another set of keys found between two of the cars? Was that footprint in the sand by one of the new windows at the back of the house significant? Why had Florence Newsom been so savaged, a blatant example of overkill? Why had the fire been set in the hallway? Was it an attempt to burn down the house and cover the murders? If so, why hadn’t it been fueled by the paint thinner and other volatile substances so handily available in the part of the house that was being remodeled? Had the purpose of the fire been only to burn a specific item or items? Had the killer or killers come only to find and destroy such items? Had they been found in Bob Newsom’s briefcase? Why was the briefcase empty? Gentry realized that he would have to find the answers to many hard questions before he could put this case behind him.

“The son and grandson just arrived,” one officer told Gentry, motioning down the driveway.

Rob Newsom had arrived from Greensboro, driven by his friend Tom Maher, while Gentry was inside the house. Gentry walked to the foot of the driveway and was told that Rob had been taken to Fam Brownlee’s house down the street, so Gentry went to his car, got one of the legal pads on which he preferred to take his meticulous notes, and walked the short distance to the old farmhouse.

Related: Married to a Murderer: 5 People Who Unknowingly Married a Killer

Rob was in the living room with his father-in-law, Fred Hill, and his parents’ pastor, Dudley Colhoun, who had come to comfort him. He looked to be in shock. At times he sat with his head in his hands. “I can’t believe this has happened,” he kept repeating.

Gentry introduced himself and offered condolences. He had a few questions. Basic things. Ages, address, occupations of Rob’s parents. When was the last time he’d seen them? How had he learned of their deaths?

Rob told about his parents spending weekends with his grandmother, their plans to move in, the remodeling that had been under way. Briefly, he went through the events of the day, his futile attempts to reach his parents, the call to the Suttons.

Did Rob know why anybody might want to kill his parents and grandmother?

He didn’t.

Had there been any problems, any unusual events in the family?

“Well, last summer,” Rob answered, “my sister’s former mother-in-law and sister-in-law were murdered in Kentucky.”

Want to keep reading? Download Bitter Blood.

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Lineup to continue publishing the true crime and creepy stories you love.

Featured photo: Open Road Media / Jerry Bledsoe