In July 2019, Ari Aster's vivid daytime nightmare Midsommar terrified summer moviegoers, reviving interest in the hallowed tradition of folk horror. Rich with sinister townsfolk, spooky agrarian villages, and blood-streaked occult rituals, folk horror tales have terrified genre fans for decades, spanning books as well as TV and films.

Notable examples include the 1970s horror flick Wicker Man and Stephen King's 1977 short story, "Children of the Corn," featured in King's short story collection Night Shift and adapted into the 1984 supernatural horror movie, Children of the Corn.

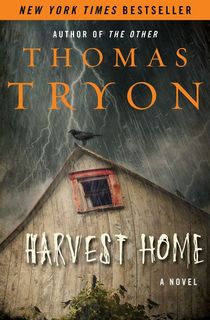

And then there's Thomas Tryon's pagan horror classic, Harvest Home.

Released in 1973, the same year as Wicker Man, and widely credited as the inspiration for Stephen King's occult narrative, Harvest Home was a New York Times bestseller and an influential entry in the folk horror genre.

Related: 10 of the Most Haunted Places in New England

The book follows a city-dwelling family, comprised of artist Ned Constantine, his wife, Beth, and daughter, Kate. Like many urbanites, they're exhausted by life in the city. They want to slow things down and mend their strained relationship … so they decamp for the country and soon find themselves living in the isolated agrarian village of Cornwall Coombe, Connecticut.

After moving into a 300-year-old farmhouse, the Constantines feel like fate delivered them into this tight-knit community. The want to know more about their new neighbors—a seemingly traditional religious group. But the family soon discovers the townspeople—especially the women—are into something much, much darker.

And it all stems from a reverence to their chief agricultural product: corn.

Kate is the first to notice that something isn't quite right with longtime resident and postmistress Tamar Penrose and her teenage daughter Missy. Known as the town oracle, Missy wanders the streets, mumbling to herself in a strange and off-putting manner. Yet the women dote on her, worshiping her alleged powers of predicting elements of the annual corn harvest.

Ned also finds himself wanting to know more about Missy and her grisly vision ritual—a choice he'll soon come to regret.

Read on for an excerpt of Thomas Tryon’s horror classic Harvest Home, then download the book.

Later it cooled slightly, the shadows began to lengthen as the sun dropped, and the Common settled into somnolence. The air was still and heavy and smelled faintly sour, the odor of weeds or grass cuttings. The pennants hung limp and tired on the booths. No traffic passed, no voices called, no dogs barked. All was silence.

I went across the roadway in the direction of Penance House, where I had seen some of the men disappearing. Wondering what had taken them there, I walked past the post office, and when I heard low voices from behind the barn next door, I went to investigate. Abruptly the voices stopped. In the stillness, I could feel the same prickling at the base of my neck I had felt that morning, and a lifting of the hairs along my forearms. An uncanny feeling, telling me something was about to happen. I took several steps toward the barn, then halted, riveted by a sound I instantly recognized, climbing to a terrible pitch, a wild cry, rising upward and outward as though from the heart of a bell, to float, then to die in the air, trailing away into nothingness. A pair of swallows, alarmed, took abrupt flight from the eaves of the barn, arcing out against the sky, dipping and swooping past my vision. I rounded the corner of the barn and was confronted by a baffling semicircle of backs. No one turned. Why so still, these men and boys, why so grave, so silent?

Then I saw the child, and thought at first she must be hemorrhaging, so red were her arms. I saw Will Jones’s simple farmer’s face looking at me. In hat and overalls, he stood meekly in the center of the circle, the handle of his sickle clasped loosely in one hand, the sharp silver crescent gone red. At his feet lay the felled sheep; below the red wool its thin legs still jerked. The child knelt in the dust, busily engaged as she gazed dreamily down at the red mass of viscera she held in her palms, her arms red to the elbows.

She raised her blank face and, as though waking from a dream, peered around the circle of men stolidly looking upon her and upon the red maw of the sheep’s cleaved belly and upon the still-palpitating entrails she tenderly cupped in her hands. Dripping red, the glossy tubular glands and bulgy membranes slid about and slowly slipped through her splayed fingers and fell back into the parted red cavity beneath them. Never removing her eyes from her hands she raised them palms upward before her, toward the sky, their redness trembling against the blue. There was no sound, only the dry rattle of the watchers’ breath trapped in their throats; one man coughed, another blew his nose into a bandanna. Still the red hands remained outstretched; as if in a trance, the child rose and began a slow circuit, her eyes glazed, uttering not a word as she moved around the circle of younger men. Stiffly she walked past young Lyman Jones, past the Tatum boys, past Merle Penrose, past several others, until she stood before Jim Minerva. A faint sign of recognition appeared in her face, a perceptible widening of the eyes, a murmur in the throat. Her hands moved slightly as if to touch him; then she passed on in her dream and in her dream stopped again, reaching out her hands and laying their redness against the cheeks of Worthy Pettinger.

A sigh, a murmur; stillness. The whir of insect wings.

When she took the hands away, a replica of each palm lay upon Worthy’s flesh, and as she slowly turned, she dropped her hands almost to her sides; not quite, for in her dream something told her to hold them away from her dress. Some of the men gathered closer to Worthy—pale now around his bloody marks—and thumped him on the shoulders, congratulating him, while others dragged the sheep aside, leaving a smeared trail of red upon the brindled ground. Several men lit up their pipes, scratching blue-tip matches on the seats of their overalls, exchanging nods and low remarks. Out on the street a car backfired, jolting me into shocked reality. I looked again, saw dust and straw and blood, heard the dull buzz of flies, the dry hiss as someone took breath in through his teeth, smelled the stench of the animal. The women came running from the Common in pairs and groups, looking at the ring of men, all amazed.

“Did she choose?” they wanted to know. Who? Who was it? Was it Jim? Jim Minerva? “No,” said the men, shaking their heads, moving aside, and “Praise be!” the women cried, seeing the marked boy. They kissed him, hugged him, bore him away, the men following, until there was no one behind the barn except me.

And the gutted sheep.

And Missy Penrose.

Related: 46 Gripping True Crime Books from the Last 54 Years

Breathing through her mouth, she was making strange, incomprehensible sounds as she stared at the open cavity. “Mnn—mean—um—nmm—” Where all had been red before, now a black liverish-looking bile was running from the rent tissue. She stopped, put her fingers into it, brought them out bloodier, darker, held them against the sky, her body going rigid and beginning a tremulous shaking.

“Mean—um—nmm—mean—”

Her eyes rolled upward in their sockets; a slight spittle appeared at the corners of her mouth, became a froth. She twitched, jerked, then a stiff arm rose, a red finger pointed at me. A rising breeze caught her hair, lifted it across her eyes; she brushed it away; red appeared on her forehead like a stigma.

I stared back, feeling the same chill again, the same cold sweat. Wind was whipping the grass at her feet. I said nothing. She said nothing. Her eyes were glassy, blank; I knew she could not see me. Yet she saw—something. Then, still pointing, red, she began screaming. I stood frozen in terror. From the Common came the tumult of celebration. No one had seen, no one saw. She was screaming louder than I thought it possible for a child to scream, and screaming, she pointed.

She stopped. Her arm fell and hung limp, her eyes came into a kind of focus; she stared briefly at the dead sheep, then turned and walked away.

Related: John Billington: The Mayflower Pilgrim Who Was Executed for Murder

The air began to freshen, the wind to change, and the sky by slight but perceptible degrees to darken, and out on the Common I could see the men standing back as the women rushed to engulf the child, touching and petting her, a murmur sweeping through them, becoming chatter, then acclaim; then, as the child fainted, their voices were suddenly stilled, like birds before a storm.

I went behind the barn and vomited into the grass.

Want to keep reading? Download Harvest Home.

Harvest Home

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Lineup to continue publishing the true crime and creepy stories you love.

Featured photo: Bryan Minear / Unsplash