When we think of serial killers, the name Ronald Joseph Dominique doesn’t necessarily come to mind. But while Dominique—who was later given the moniker "the Bayou Strangler"—never gained the notoriety of the Dahmers and Gacys of the world, his crimes were no less heinous. In fact, his body count makes him one of the most prolific killers in American history: 23 men died at Dominique’s hands between 1997 and 2006.

So how did a vindictive killer evade the police for nearly a decade? Dominique’s success can be attributed to two factors: As a pizza delivery man, he maintained a low profile in his Louisiana town. No one suspected that Dominique—an overweight and balding 30-something—was capable of murder. Likewise, his victims—primarily gay African American men—lived on the fringes of society. With the promise of paid sex, Dominique would lure these men into his car before raping and then strangling them to death. Only years later, after DNA evidence linked him to the crimes, was he finally put behind bars.

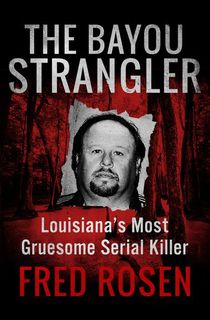

Dominique's little-known but staggering murder spree is examined in Fred Rosen's book, The Bayou Strangler. The excerpt below describes one of Dominique's first killings—that of Oliver LeBlank, a man he picked up at a gay bar—and introduces one of the detectives who brought Dominique to justice.

He’d had enough, and he’d been forced to put up with too much to stop there. The ridicule, the stone glances from his family, and now just thinking someone was about to violate him again made him want, finally, to do something about it. It was an intoxicating combination of fear and retribution. And he had prepared for just such an eventuality.

Reaching down to the floorboards, he felt the cold metal of the tire iron in his strong hand. He brought it up quickly and slammed it into the side of Oliver LeBanks’s head. He brought up the iron and hit him again. As the smaller man’s brain began leaking out blood inside his cranium, the struggle seeped out of him. His limbs stopped pushing, then twitched, finally going slack.

Physicians call it a concussion. Unless LeBanks were operated on immediately, the twin concussions he had sustained when the tire iron impacted his head would soon kill him. Dominique showed no mercy. He got on top of LeBanks and began to choke him.

Already unconscious from the blows, LeBanks started twitching again, and then Dominique heard the death rattle, the last gasp of the life that he had just violated. He took off his belt, wrapped it around the now unmoving figure. Putting his weight on top of him again, Dominique pulled the belt tight, so it bit into LeBanks’s skin.

After a while—Dominique wasn’t sure how long it was—he realized the guy was once and for all not breathing anymore. He threw open the back door and jumped out of the station wagon into the deserted street. Dominique had killed before. He knew what he had to do. He got into the driver’s seat, fished his keys out of his pocket, plunged the key into the ignition, and started up the car.

Dominique began driving down dark streets, not really knowing where he was, looking for the right place to dump the body. He’d know when he saw it. He wound up driving into Kenner, the oldest city in Jefferson Parish, established in 1855. Back then, the place was known by its French name, Cannes Brûlées (burnt cane fields).

It was a landmark on the banks of the Mississippi River. The family of its founder, William Kenner, owned many of the area’s larger plantations and farms. Everything changed in 1915 when a commuter rail line was established from Kenner to New Orleans, bringing in manufacturing. That, in turn, brought in new roads and the airports.

A full-fledged suburb, Kenner was connected to the Big Easy by Interstate 10, the major east/west interstate in the southern United States. Interstate 10 goes all the way from Jacksonville, Florida, on the Atlantic Ocean, across the southwestern United States, terminating at Santa Monica on the Pacific Ocean in California.

A few miles north of the busy New Orleans International Airport, Dominique turned his tan Malibu wagon south. He took a left down Airport Road. As he circled the airport looking for a location that he would know instinctively was right, the overhead jets had a bird’s-eye view of his travels.

Too many people, too many cars; the place was just too active. What had he been thinking? No place to do it that wouldn’t be easily found. But that was part of the kick for Dominique. It couldn’t be too easy, he wanted the body to be found. Had he not, he could have easily just gone over a bridge and dumped it into some dark waters.

Or he could have driven to a nearby bayou and let the alligators take care of things, neatly and tastily, without leaving a trace for a forensic specialist to work with. It just wouldn’t scratch that itch inside him if he did that. What fun would it be? What pleasure it would give him when the body was found!

The body had to be found.

He was sick and tired of people not giving him credit for things. Now he’d show them. He’d killed again and the body would be proof. Proof.

He took a left onto Airline Drive, also known as Federal Highway 61. Heading east, back toward New Orleans, he passed the Hilton and Lexington hotels again, their entrances lit up like it was Christmas.

Dominique was one of those people who loved Christmas all year round. He kept Christmas decorations up full-time in his trailer. But this wasn’t the holiday season. Those lights meant people were around, people who might see him and what he was doing, what he had done.

Again, too busy, too many people driving in and out. No, that wouldn’t do, and he kept going.

He passed food management and construction offices. Airline Drive is host to a variety of businesses that cater to the airline traveler going through New Orleans. After a few miles, Airline Drive passed into the town of Metairie (pronounced MET-ur-ee).

Dominique saw Providence Memorial Park Cemetery on his right, where Mahalia Jackson, the celebrated gospel singer, had been laid to rest. But he was hardly into gospel. Leaving Mahalia and the cemetery behind him, he continued east toward New Orleans, still on Airline Drive, passing the fast food and chain restaurants, gas stations, and strip malls that dotted the highway.

Passing Little Farms Avenue, he approached Dickory Avenue. Just past the light at the intersection of Dickory Avenue and the end of the Earhart Expressway was a speed trap. Waiting for speeders at the bottom of the elevated highway was Louisiana state trooper Cal Calhoun. His job was to catch and ticket speeders, who would not see his car hidden in a parking lot at the bottom of the exit ramp.

Obeying the speed limit as he always did, Dominique drove right past the cop. Dickory Avenue rose as it got to the six-thousand block of Stable Drive before hitting the railroad tracks. Below Stable was a feeder road into Zephyr Field a quarter of a mile east, where the Triple-A New Orleans Zephyrs minor-league team played its home games.

There was nothing special about the overpass except that it was conveniently there, secluded but accessible to passersby. Perfect for dumping a body. The tan Malibu wagon tooled down Stable Drive, deserted at this hour. Dominique pulled the wagon to the side of the road, hopped out, went around to the passenger-side door, and threw it open.

“Pulling LeBanks’s corpse by the belt still wrapped around its neck, he struggled until he had it fully out under the overpass. Then he let it go. The body plunked down on the sand, face down. Cutting back quickly to the station wagon, Dominique closed the rear passenger-side door, which made a hollow sound in the empty darkness.

Getting back behind the wheel, he turned the ignition on and put the car into drive. A moment later, Ronald J. Dominique was well away, driving the few blocks north to Airline Drive. This time, he didn’t circle the airport, but kept going. Ten miles down the road, he saw the interstate looming overhead.

Interstate 310 is a freeway linking US 90 and Southern Louisiana to Interstate 10 and metropolitan New Orleans. He turned right up the ramp, then took a left and headed southwest. In seven miles, the road climbed higher and passed over the Mississippi River, providing Dominique with a great view of the Big Muddy flowing below him.

On the other side, the road passed over Westbank Bridge Park and curved south. In front of him were two signs. The one for the right lane said “90 West, Houma,” while the one for the left said “90 East, Boutte, New Orleans.” Dominique followed the sign to Boutte, at the southern end of the roadway. He turned north on the Old Spanish Trail, pulling off at the trailer park where he lived.

Trailers were everywhere. Some were set on wooden foundations, some on concrete; some had gardens in front; and some were really modular homes. The one thing they had in common: anonymity.

The next day, a passerby saw the body below the freeway ramp and called the police. Because the corpse had been dumped in Jefferson Parish, the lead homicide investigator from the sheriff’s office was summoned to the scene. If it should turn out that the victim was killed in, say, Terrebonne Parish, the latter would then assume venue, but for now, Jefferson was up at bat.

This guy is sloppy, thought Dennis Thornton. Otherwise, how come we find a fresh body?

Dressed like a banker in charcoal-gray suit, blue tie, and wing-tipped shoes, Detective Lieutenant Dennis Thornton bent over and examined the partially clothed body of the man he would eventually identify as Oliver LeBanks.

Murder was a much more frequent occurrence in Louisiana than in other places, and therefore, not unusual. Louisiana and in particular the New Orleans metropolitan area has the highest per capita homicide rate in the country. Sorting through the similarities and differences between so many homicides can be a daunting task.

Linkage. It was all about linkage in serial-killer cases. Do that and you’d save lives. Link homicides to the same perpetrator and concentrate your resources there. It was an inviolable clock, ticking away the life-seconds of the next victims.

Thornton looked up at the jets flying overhead. The airport was nearby. Did the killer live near the airport? he wondered.

“Yes, he did. But what Thornton didn’t know was that the killer was closer than anyone realized. And LeBanks had not been his first victim. The first had been David Mitchell, a nineteen-year-old African American, who was last seen on July 13, 1997, in St. Charles Parish. That’s right up Interstate 310, not far from where Dominique was living in Boutte.

Mitchell’s fully clothed body was discovered the day after his disappearance on Louisiana Highway 3160, off Highway 18 in an industrial area of the parish. He had been anally raped before being drowned.

Dominique next struck exactly five months later to the day, again close to home.

Gary Pierre, a twenty-year-old African American, was found dead on December 14 in St. Charles Parish. The coroner ruled that Pierre had been murdered “by asphyxiation, due to neck compression.” He too had been raped.

Serial killers can change patterns. Sometimes they have a cooling-off period between crimes. Dominique seemed to be one of those. Consistent to his pattern, at least for the moment, Dominique once again took a vacation from killing, this time for seven months. Then Larry Ranson showed up.

Like Mitchell and Pierre, he was African American and had last been seen in St. Charles. Ranson was thirty-eight years old. Dominique was changing his victim of choice, showing age wasn’t a factor. Serial killers usually zero in on a type and remain constant.

Ranson’s fully clothed body was discovered the day after he disappeared on July 31, off Louisiana 316 in an industrial area of the parish. The coroner later said Ranson’s manner of death was “asphyxiation due to neck compression.” Ranson would have been conscious the whole time he was being choked until, mercifully, he blacked out because his brain wasn’t getting air and drifted into death.

Because the bodies had been dumped close to one another off the same road, the police in St. Charles suspected one killer. But the culprit had left nothing behind for the cops to work with—no fibers, no prints, no hair. The lack of DNA, plus the anal bruising of the victims, made the cops figure he was using a condom. They sorted through the usual list of parolees with charges of sexual abuse of one sort or another in their files, but came up with nothing.

What Southern Louisiana was unknowingly facing was a serial killer, and a successful one. Once a serial killing has been confirmed in a locality, the FBI is contacted and they make a profile of the killer. The profiles are generally cookie-cutter.

“The serial killer is white, poor, and doesn’t have much of an education.”

While that profile would certainly fit Dominique, it also fit a couple million other guys in Louisiana and would be of no practical use.

Solving a serial killing means thinking outside the box. Once in a while, a detective will get assigned to investigate and no matter where the trail leads, no matter how long it takes, the detective decides to dedicate part of his life to tracking down a murderer who had the audacity to kill in his parish. Dominique didn’t know it, but he had made an enemy of Dennis Thornton.

Evidence markers were set up near tire imprints in the soft sand where LeBanks’s body had been dumped. There was no evidence of a murder weapon. Examining the body, Thornton saw that the victim had been bludgeoned on one side of the head. The killer had left the pants of the victim down below his knees. His shirt was off.

Thornton wore surgical gloves to prevent contamination. Not that he was afraid the dead man could contaminate him; it was the other way around. The idea was that the detective bring nothing to the scene, including his own fingerprints, that could contaminate the evidence. Thornton picked up the wrists and noted the ligature or binding marks. It looked like the guy’s wrists had been tied together. Thornton was going to be very interested in what the coroner had to say about them.

As the morgue attendants moved in with the bags, tarps, and collapsible table that formed the tools of their trade, Thornton stepped back to allow them to do their job.

You can never be sure how wrists are tied together until the coroner weighs in. And details like the pants around the victim’s ankles could turn out to be the killer’s signature behavior.

Want to keep reading? Download The Bayou Strangler now.

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Lineup to continue publishing the terrifying stories you love.