“What do you know about horror films?” Stanley Kubrick once asked Emilio D’Alessandro, his personal driver.

In 1977, Stanley Kubrick began work on what would become one of the most haunting films of all time: The Shining. Though the movie was met with mixed reviews and mediocre box office sales upon opening, it soon gained momentum and is now considered a classic.

But what really went into making such a horrifying film? From the incredibly slow production time, somewhat due to Kubrick’s insistence on reshooting scenes—the most famous being the scene in which Wendy (Shelley Duvall) is swinging a bat at Jack (Jack Nicholson), which took 127 takes—to his feud with author Stephen King, life on the set of The Shining was anything but tame.

Kubrick’s long-time companion, Emilio D’Alessandro, dives deep into the director’s life story as he recounts the ups and downs of life at the side of a demanding genius.

Read on for an excerpt of Stanley Kubrick and Me.

A few hours later he returned to the subject and tried to explain why he had chosen Nicholson: “You’ll see, everything about Jack is perfect for this role: his expression, even the way he walks. He doesn’t need anything extra to play this part. It’s all already there inside him. He doesn’t even need speech training like Ryan did for the Irish accent.” And it was true: there wasn’t much difference between Jack Nicholson off the set and in the film. All he needed was the little velvet jacket that Milena had bought him, a bit of makeup, his hair quickly brushed, and, voilà: he was Jack Torrance. Day after day, he was faultless. He never got a line wrong and always had a professional, collaborative approach. He listened to Stanley and did what he asked. Actually, he did even more than he was asked to do: after he’d done a scene the way Stanley wanted it, he asked to do another take because he’d had a new idea. Only a few days after shooting had begun, I realized that I completely agreed with Stanley when he said that Jack was born to play that part. Jack realized this “himself, too, and he enjoyed every minute of it.

Shelley Duvall, his costar, seemed to me a bit vulnerable. When I met her, she had just finished her interview in Stanley’s office. She reminded me of Olive Oyl in the Popeye cartoons: she was incredibly slim and her arms dangled by her sides. Vivian was in the office that day too, and I remember noticing that Vivian was the only person Shelley smiled at. It was as if, unlike the others, Vivian didn’t intimidate her. Marisa Berenson had made a completely different impression on me. Even if she had been a bit worried about meeting Stanley, she was still happy to talk to me in an amenable and friendly way. Shelley had hardly even said hello. I didn’t think that she and Jack seemed right for each other. Could that be the effect that Stanley was looking for?

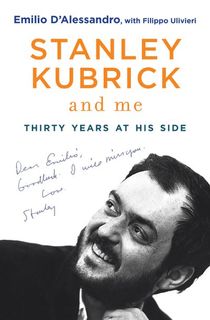

Emilio D'Alessandro (the author).

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Sky Horse Marketing ServicesIn the days that followed, Stanley started to shoot the scenes with the two actors. It became immediately apparent that there were problems. As usual, Jack took up his position in front of the camera and delivered his lines with the determination of a charging bull. Shelley on the other hand was hesitant, and as soon as she made a mistake she stopped, afraid that she had ruined the take. When Jack made a mistake he just kept going. He improvised or tried to patch it up somehow so that he could at least finish. That way he gave Stanley the chance to think about the scene as a whole. “Don’t worry. If it’s not right, we’ll do it again,” said Stanley in an attempt to calm Shelley down, but she just became more and more insecure.

“Shelley, do the scene just as I told you, and then after we’ll see if it’s okay,” Stanley insisted.

“You always say okay to Jack. Why don’t you ever say that to me? Is there something wrong?” she asked, bewildered.

“Shelley, just do the scene.”

Want more book recommendations? Sign up for The Lineup’s newsletter, and get them delivered straight to your inbox.

I never heard Stanley treat her really unkindly, but I had no doubt that she found filming the scenes emotionally exhausting. One day, the driver who had been assigned to her by the production company took me to one side. “When I take her home in the evenings, I can hear Shelley crying on the back seat,” he said. “Are there problems on the set?”

“Nothing,” I answered. “Everything’s just fine. Try to reassure her a bit if you can.” The driver was a good person, and on the trips home he said to Shelley: “They told me that there’s nothing to worry about. Stanley is very happy with you.” Vivian was the only one who was able to comfort her. Whenever there was a break, Shelley went to stay with Vivian and at last a smile appeared on her face. But when Stanley appeared, Shelley left Vivian immediately and went to stay on her own again. Vivian came to me and asked: “Am I doing the right thing by talking to Shelley? As soon as Dad appears, she runs off. Has he told her not to talk to me?”

The last shot of "The Shining."

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Sky Horse Marketing ServicesJack’s personality didn’t exactly help to calm things down. He loved to rule the roost. He was always making vulgar remarks full of sexual innuendo. He made faces at anyone who turned their back on him and flirted with anything in a skirt. Basically, he invaded other people’s space, and in particular, Shelley’s.

To be honest, I didn’t hit it off all that well with Jack myself. On the few occasions I drove him somewhere, he always had something to say about the girls we passed in the street. “Hey, slow down a bit Emilio, I want to take a look at this wonderful lady.” So I had to slow down to keep him happy. “Ah ha,” he smirked when we had gone past, “that one was really special.”

***

I saw how special effects worked for the first time on the set of The Shining. There were some violent scenes in the film, full of blood and injured actors. There were winter storms too, with snow and other weather effects. Stanley talked to the head of the special effects team before they started, and then left him to get on with it without interfering. When the work was done, he reappeared and said what he thought, which was usually either “Okay” or “Start again from scratch.”

The latter answer had been tormenting the special effects team for weeks. They had tried and tried again to produce fake blood that convinced Stanley, but he was never satisfied with the color. They’d found the right viscosity more or less immediately. The problem was the tone of reddish-brown that he wanted. They also had to make sure that the materials they used were biodegradable and nontoxic. An enormous amount of this blood was needed on the set, and it wouldn’t be easy to get rid of. If it was water-based with natural colorings, they could simply pour it down the drains. Take after take, liters and liters of the stuff were disposed of like this at EMI Films. The fake blood flowed along the gutters and reached the village of Borehamwood. The roadside ditches turned red, and there were points where this brownish liquid stagnated before it soaked into the ground. Two of the domestics at Abbots Mead lived in Borehamwood, and one day they arrived alarmed and shouting: “There’s been a massacre, a massacre!”

Want to keep reading? Download Stanley Kubrick and Me.

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Lineup to continue publishing the true crime and creepy stories you love.

Featured photo: courtesy of Sky Horse Marketing Services