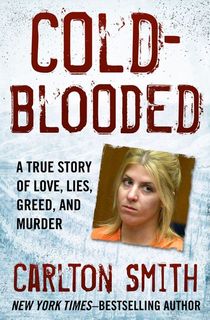

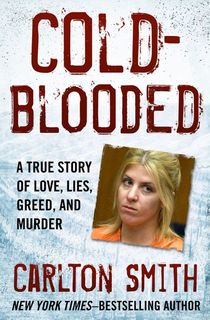

On September 11, 2001—a day that holds significance of a very different kind for most Americans—Larry McNabney went missing. His fifth wife, Elisa, claimed that he had fled the horse show they were at in Los Angeles to join a cult in Florida. But there was a problem with that story.

All flights were grounded on the west coast starting at 6 A.M. local time. So just how did Larry get across the country while his vehicle was still in California? There was much more to this story than Elisa was telling. For starters, Elisa was not her real name. “Elisa,” who was born Laren Sims, had a total of 38 aliases over the years.

And when Larry’s body was discovered buried in a vineyard in March 2002, it became clear that this was murder. But before police could question "Elisa" about her husband’s murder, she was gone. Once again "Elisa" changed her name, dyed her hair, and raced towards a new life on the other side of the country, causing a nationwide manhunt.

Carlton Smith’s true crime classic, Cold-Blooded, examines the case’s key players and searches for a motive behind why a wife would kill her husband.

Read on for an excerpt from Cold-Blooded, and then download the book.

By the late afternoon of February 5, 2002, San Joaquin County Sheriff’s Homicide Detective Deborah Scheffel decided to button things up for the day. The light was fading fast, and Scheffel didn’t want to overlook anything in the gloom. The body would keep—it had been there for some time and wasn’t going anywhere. Not now.

The call had come in around 4 in the afternoon. A dog belonging to several farm workers had “keyed in on” something in a low swale of the vineyard they were working in, according to the San Joaquin County Coroner’s Office’s later report. The three farm workers looked to see what their dog was so excited about, and discovered a human leg bone sticking out of the ground. All the flesh had been gnawed off by insects and small animals.

The farm workers returned to their houses, not far away, and called the vineyard’s owner, who in turn called the sheriff’s department. As it happened, it was Detective Scheffel’s turn to be up on the homicide rotation, so she went out to the scene in the late afternoon.

Scheffel at first suspected that she knew whose body it might have been. She had just finished testifying in a rather complicated serial murder case involving two killers who sometimes acted together, sometimes separately. Police had been unable to locate all the victims of the disgusting pair, and Scheffel guessed this was probably another one of those lost victims. She hoped so, for the sake of the families whose loved ones had still not been accounted for.

But when she arrived at the scene in the vineyard off Frazier Road near Clements Road, northeast of Lodi, she realized that the victim had been far too recently buried to be one of the serial killers’ victims. Those people had been missing for several years, and this body hadn’t been in the ground for more than a few weeks.

In order not to lose any valuable information while recovering the body, Scheffel decided to wait for better light the following day.

By the next morning, Scheffel had rounded up several experts—a pathologist, Dr. Terri Haddix; a forensic anthropologist, Dr. Roger LaJeunesse; and a criminalist from the state department of justice—to remove the body from the ground. The work began when the forensic anthropologist strung up grid lines around the grave site, exactly as if he were excavating an ancient burial mound.

As dirt was removed, first by shovels, then trowels and eventually a small butter knife, it was put into buckets. The buckets were taken to a screen mesh to be sifted for any potential trace evidence, such as hairs and fibers, or other small items that might otherwise be overlooked. A pair of rusty scissors with red handles was found near the grave, along with a beverage bottle produced in Mexico.

Within a short time, much of the body was uncovered, and Scheffel realized that the victim had been a man of middle age, rather large, and clad only in boxer shorts and part of a tee-shirt, which appeared to have been cut, possibly by the red-handled scissors. The man had a distinctive tattoo on his upper arm. What was strange was that the dead man seemed to be lying on his back, in a near-fetal position—that is, his knees were drawn up toward his chest, arms crossed, and his head was bent forward.

Scheffel began to consider the possible identity of the victim. One that popped into her mind almost immediately was the missing Sacramento lawyer, Larry McNabney, whose case was then receiving substantial publicity and air time in central California.

Dr. LaJeunesse, the forensic anthropologist, did the majority of the excavation. He soon formed the opinion, based on the relative lack of decomposition, that the body had not been buried for very long. He asked if the detectives were looking for someone.

And they said, ‘We have an attorney that we are looking for, but he’s been missing since September,’” LaJeunesse said later. “And I said, ‘Well, from this grave, I don’t think that would be the individual, because this body has not decomposed to that extent,’ which I would have expected had that individual been buried in September.”

Apart from the relatively intact condition of the body, LaJeunesse pointed to the yellowed grass that had been unearthed from the grave. The grass had probably grown in December, he said, and when the body was buried, the grass was buried with it.

At length, the exhumation was completed, and the body was taken to the San Joaquin County forensic pathology facility—the morgue—south of Stockton in French Camp, to await an autopsy by Dr. Haddix.

That began the next morning, February 7. Dr. Haddix was immediately struck by the absence of any obvious fatal injuries to the body—no gunshot wounds, no stabbing, no clear evidence of blunt trauma. Like LaJeunesse, Haddix was convinced that the remains had been buried relatively recently. In fact, some of the blood in the body was still in a liquid state. Probably the only overt sign of injury Haddix noticed was a surface hemorrhage in the muscles of the upper back area. But that was it—no broken bones, no internal injuries.

Meanwhile, Jose Ruiz, an evidence technician for the sheriff’s department, took fingerprints of the corpse. Within a short time, Ruiz had matched the prints of the dead man to a set of fingerprints given to him by Scheffel.

The dead man was Larry.

But how could it be Larry? Larry McNabney was supposed to have disappeared in early September, and this body had only been buried for a little over a month. If the body was Larry—and the fingerprints proved that—where had he been all that time? And more to the point, how had he wound up in the vineyard, when he’d last been seen in southern California?

Haddix, LaJeunesse and Scheffel discussed the matter, trying out the possibilities. If Larry had died in early September, Haddix was convinced, there was no way that he had been in the vineyard grave since that time—the body was too well preserved.

Preserved—that started people thinking. Had the body been frozen? No, Haddix said—otherwise there would be evidence of tissue damage from the freezing process. Well, what about a refrigerator?

That would do the trick, Haddix said—assuming that one could find a refrigerator large enough to contain a six-foot, two-hundred-pound man. They recalled the way the body had come out of the ground, folded up—as if he had been compacted. It fit. So did the hemorrhage across the upper back, which might have come from the interior surface of a refrigerator as the body was crammed inside.

That raised another possibility: had Larry been alive when he was put into a refrigerator? The hemorrhage suggested that it was possible, since bleeding generally stops once the heart stops. That meant it was possible that Larry had actually suffocated to death. But if that had happened, Larry had been so near to dying, no other evidence of suffocation was apparent.

How would a previously healthy 53-year-old man get into a refrigerator to die? The obvious answer was, after some sort of poisoning that left him either dead or too weak to resist. Haddix took samples of organ tissues, the hair, blood, stomach contents, and portions of the brain, along with the shorts, tee-shirt, and mud that had adhered to the body, and sent them all out for testing. There was an explanation for what had happened to Larry McNabney, and Haddix was determined to find it.

Want to keep reading? Download Cold-Blooded now.

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for The Lineup to continue publishing the creepy stories you love.

Featured photos: Lauren Sims (Hernando County Sheriff) and Larry McNabney (Murderpedia)