By February of 1979, 98% of Americans said that they had heard of the tragedy which took place at the Peoples Temple Agricultural Project (known colloquially as “Jonestown”) in Guyana, leading George Gallup to state that “few events, in fact, in the entire history of the Gallup Poll have been known to such a high percentage of the U.S. public.”

Even now, we are all familiar with the phrase “drink the Kool-Aid,” a neologism referring to the tragic events of what has since been dubbed the “Jonestown Massacre.”

Yet today, on the 47th anniversary of the horrors of Jonestown, what do we really know about what happened there on November 18, 1978?

Jim Jones and the Formation of Jonestown

Subsequently labeled a “cult of death” by both Time and Newsweek, the Peoples Temple had more innocuous beginnings. By most accounts, Jim Jones was an odd and charismatic individual who was born in Indiana in 1931 and showed an early interest in death, religion, and politics.

By 1955, he had founded his own organization in Indianapolis, one that would become the Peoples Temple.

The Peoples Temple practiced what Jones referred to as “apostolic socialism,” inspired by everyone from Joseph Stalin, Mao Zedong, and Adolf Hitler to spiritual leaders such as Father Divine and William Branham.

Jones rejected what he saw as U.S. capitalism and imperialism, and embraced racial integration, referring to the Peoples Temple as a “rainbow family”—at the time of the Jonestown Massacre, roughly 70% of its population was Black.

Early on, Jones enjoyed considerable political support, including from Vice President Walter Mondale and First Lady Rosalynn Carter. Harvey Milk once wrote a letter to President Jimmy Carter in which he defended Jones as a “man of the highest character.”

This support helped Jones to grow the Peoples Temple and, eventually, to establish the settlement that would become Jonestown in the jungles of Guyana.

White Nights: Life in Jonestown

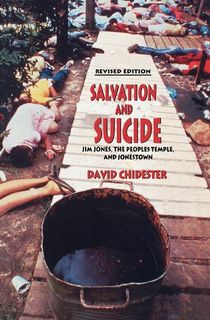

Thanks to extensive photographs gracing the covers of newspapers and magazines, the image of Jonestown is as familiar as the tragedy which took place there.

A patchwork quilt of simple cabins with bright, white roofs, Jonestown was constructed on a parcel of land leased in northwestern Guyana and, at its height, was home to nearly one thousand people.

What was life like in Jonestown? That depends on who you ask. While defectors from the Peoples Temple alleged various abuses, and no one was allowed to leave without Jim Jones’s express permission, others described their life in Jonestown as idyllic.

Annie Moore, one of the victims of the Jonestown tragedy, left behind a note calling Jonestown “the most peaceful, loving community that ever existed […] a paradise in the jungle.”

What we do know is that removal to Guyana did not assuage Jones’s concerns about the future of the Peoples Temple. As his own health declined, he apparently became increasingly paranoid about outside enemies and political persecution – and he began laying plans accordingly.

Even in the years before the founding of Jonestown, Jones had already explored the concept of “revolutionary suicide,” a term first coined by Black Panter founder Huey P. Newton. This was the solution that Jones proposed for his followers—one that he practiced in Jonestown in a series of “White Nights.”

“Everyone, including the children, was told to line up,” Temple defector Deborah Layton said in an affidavit, describing one of the “White Night” drills.

“As we passed through the line, we were given a small glass of red liquid to drink. We were told that the liquid contained poison and that we would die within 45 minutes. We all did as we were told. When the time came when we should have dropped dead, Rev. Jones explained that the poison was not real and that we had just been through a loyalty test.”

“Something Was Very, Very Wrong”

On November 14, 1978, Leo Ryan was an active representative of California’s 11th congressional district who led a delegation to visit Jonestown, partly prompted by worries expressed by a group of people related to members of the Peoples Temple, who called themselves the Concerned Relatives.

Several of the Concerned Relatives accompanied Ryan on his trip, along with advisors, staffers, and reporters.

While Ryan was visiting Jonestown, his delegation was slipped a note by at least one member of the Temple that said, “Please help us get out of Jonestown.” According to Jackie Speier, Ryan’s legal advisor, this led the congressman to realize that “something was very, very wrong.”

Despite this, only a small handful of defectors attempted to leave with Ryan’s delegation, and Ryan told attorney Charles Garry, who had represented the Peoples Temple on several occasions, that he planned to report on Jonestown “in basically good terms” and that even if more had wanted to leave, “I’d still say you have a beautiful place here.”

Even these assurances were not enough to assuage Jim Jones, however. As Ryan and the fourteen defectors prepared to leave, Jim Jones told Garry, “I have failed […] all is lost.”

Drinking the Kool-Aid

As Ryan’s delegation boarded two planes to take them back to the United States, Larry Layton, a Temple member who had demanded to join the group at the last minute, produced a handgun and opened fire.

At the same time, members of Jonestown’s Red Brigade security force arrived at the airport with handguns, shotguns, and rifles. In total, five people were shot down before the planes managed to take off, including Ryan himself.

While this was happening, things in Jonestown were heading down an even darker path. With the help of the community’s on-site doctor, a large metal tub was filled with grape Flavor Aid poisoned with diphenhydramine, promethazine, chlorpromazine, chloroquine, diazepam, chloral hydrate, and cyanide.

Though Flavor Aid was the product actually used, many reports later misidentified it as Kool-Aid, leading to the rise of the popular phrase “drinking the Kool-Aid” to refer to “a strong belief in and acceptance of a dangerous, deranged, or foolish ideology or concept.”

Jones encouraged his followers to commit “revolutionary suicide” by voluntarily drinking the poison that had been prepared for them.

“I tell you, I don’t car how many screams you hear, I don’t care how many anguished cries,” he says in a 45-minute recording sometimes known as the “death tape.”

“Death is a million times preferable to ten more days of this life. If you knew what was ahead of you—if you knew what was ahead of you, you’d be glad to be stepping over tonight.”

All told, 909 people perished within Jonestown itself, most of them as a result of poison.

How many took the poison semi-voluntarily and how many had to be forced is a matter of continued dispute—and even those who administered the poison by their own hands did so with Jones’s armed guards standing nearby, offering them very little real choice in the matter.

In addition to the 909 who died in Jonestown—Jim Jones among them, dead by what appeared to be a self-inflicted gunshot wound—and the five who were shot dead at the airstrip, four more members of the Peoples Temple were ordered by Jones to commit murder-suicide at a Temple-run building in Guyana’s capital city, Georgetown, bringing the total death toll to 918.

Initially called a “mass suicide” and later described more often as a massacre, the events at Jonestown marked one of the largest single losses of American life outside a war or natural disaster until the events of September 11, 2001, and they shook the nation to its core. Nearly fifty years on, the tragedy still has the power to shake us, even today.

Featured image: Federal Bureau of Investigation / Wikimedia