There are few stories as gruesome and terrifying as the tale of Fred and Rose West. Fred and Rose got away with torturing and killing many young women and girls at their home at 25 Cromwell Street in Gloucestershire, England over the course of two decades until they were finally caught by police.

When teenage Rosemary Letts began dating the older and surly Fred West, the relationship was met with contempt from all those around her, especially her parents, due to Fred’s unkempt demeanor and Rose’s young age.

Nobody knew that their union would lead to a sadistic partnership of serial murder and sexual abuse.

After years of abusing their children and killing innocent women, the West couple was finally stopped in 1994, when the remains of their eldest daughter were found buried under the porch of the family’s home, and the discovery of more human remains followed shortly after.

Fred was found guilty of 12 murders and Rose was found guilty of 10, but some suspect the real victim count could be much higher.

Now, the mysteries and secrets of what went on at 25 Cromwell Street have been revealed in all of their horrifying glory.

The full story of the Wests’ crimes is almost impossible to believe and stands as a true example of the evil that could be lurking in any neighborhood.

Fred and Rose West: A British Horror Story on Netflix

This month, a brand new Fred and Rose West documentary was released on Netflix. The three-part documentary series tells the whole story of Fred and Rose’s lives and crimes.

The series features interviews with and updates on the Fred and Rose West children who witnessed and experienced the brutality of the couple firsthand. Also featured are previously unseen Fred and Rose West crime scene photos exposing the extremely heinous deeds.

Watch a trailer and stream the new Fred and Rose documentary below!

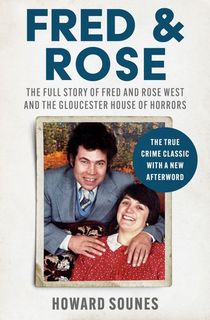

The new series, Fred and Rose West: A British Horror Story, was based on the work of British author and journalist Howard Sounes.

In 1994, Sounes was the first journalist to break the story of the crimes at 25 Cromwell Street when he reported on the mass grave found there for the Daily Mirror and the Sunday Mirror.

Sounes is now one of the top experts on the case and even acted as a producer for the Netflix series.

Keep reading for a taste of one of Sounes’ books about the case that inspired the documentary!

Read this excerpt from the first chapter of Fred & Rose below—then purchase your own copy of the book to keep reading!

1

THE BLUE-EYED BOY

The village of Much Marcle lies just off the A449 road, halfway between the market towns of Ledbury and Ross-on-Wye, in rich Herefordshire countryside one hundred and twenty miles west of London. The Malvern Hills are to the north, the Wye Valley is to the west and the Forest of Dean to the south. Gloucester, the nearest major city, is fourteen miles away across the River Severn.

At the beginning of the Second World War, Much Marcle was a village of approximately seven hundred people, most of whom were employed on the land. An ancient settlement dating back to the Iron Age, the unusual name of the village derives from Old English, meaning ‘boundary wood’; the prefix ‘Much’ sets it apart from the neighbouring hamlet of Little Marcle. The local accent is distinctive: Gloucester is pronounced ‘Glaaster’ and sentences are often concluded with the word ‘mind’, pronounced ‘minde’.

There are several grand residences in the village, including a Queen Anne rectory and Homme House, the setting for a wedding scene in the Victorian book Kilvert’s Diary. Much Marcle’s other notable buildings are the half-timbered cottages, the redbrick school house, the Memorial Hall and cider factory. Standing on opposite sides of the main road are Weston’s Garage and the Wallwyn Arms public house, and along the lane from the Wallwyn Arms is the thirteenth-century sandstone parish church, St Bartholomew’s, distinguished by its higgledy-piggledy graveyard and imposing, gargoyled tower.

The surrounding countryside is a pleasing sweep of green pasture and golden corn, with orchards of heavy cider apples and venerable perry pear trees left over from the last century, geometric hop fields and ploughed acres of plain red soil.

In fact it is such an uneventful place that a landslide during the reign of Elizabeth I long remained the most fantastical event in Much Marcle’s history. For three days in 1575 there was much fear and excitement in the parish when ‘Marclay Hill … roused itself out of a dead sleep and with a roaring noise removed from the place where it stood’, destroying all in its path, including hedgerows, two highways and a chapel. A wall of earth and stone fifteen feet high was the result of the mysterious upheaval, and it is marked to this day on Ordnance Survey maps as ‘The Wonder’.

The Marcle and Yatton Flower Show and Sports Fair has been held in a field on the edge of the village on the last Saturday in August since the 1890s. It is the main summer event in the area, a descendant of the more ancient Marcle Fayres. Stallholders sell food, fancy goods and clothing; there are also fairground rides, exhibitions and sports, including a five-and-a-half-mile road race between Ledbury and the village.

It was during the August of 1939 when the man who would become Fred West’s father sauntered down the lane from the nearby hamlet of Preston, heading for the Marcle Fair. Walter West, a powerfully built young farm hand, was born in 1914 and had been raised near the town of Ross-on-Wye. He was intimidated as a child by his army sergeant father, a forbidding character who was decorated for his service in the Great War of 1914–18. Walter complained that even when the old man came out of the army, he did not leave its disciplinarian ways behind.

With little education, barely able to read or write, Walter had left school at the age of eleven to work on the land. His maternal grandfather was a wagoner, employed to tend farm horses and their tackle; Walter became the wagoner’s boy.

He had married for the first time when he was twenty-three, to a nurse almost exactly twice his age. One of twin sisters, Gertrude Maddocks was a 45-year-old spinster with a long, kindly face. She married Walter in 1937, and they set up home together in Preston. Walter went to work at Thomas’ Farm nearby.

Gertrude was unable to have children, so the couple decided to foster a one-year-old boy named Bruce from an orphanage. Two years into the marriage, Gertrude met a bizarre death when, on a hot June day, she was stung by a bee, collapsed and died as young Bruce stood helplessly by. Walter found her body sprawled on the garden path when he returned home. After the funeral, he realised that he was unable to care for his adopted son on his own and handed the boy back to the orphanage.

Walter always spoke fondly of his first wife, despite the considerable age gap between them and the brevity of their marriage. He kept her photograph and the brass-bound Maddocks family bible among his most valued possessions for the rest of his life.

It was two and a half months after Gertrude’s funeral when Walter attended the 1939 Marcle Fair. He was loafing along between the attractions when he came to a needlework stall, where a wavy-haired girl was displaying her work. The girl was shy and unforthcoming, but Walter eventually discovered that her name was Daisy Hill and that she was in service in Ledbury. Her parents lived in a tied cottage called Cowleas, on a sloping track known as Cow Lane near Weston’s cider factory in the village. Her father, William Hill, was a familiar figure in the area: a tall, skinny man with a large black moustache who tended a milking herd of Hereford cattle. His family had been in Much Marcle, mostly working the land, for as long as anyone could remember, and were sometimes mocked in the village as being simple-minded. Because they were named Hill, and their home was built on a slight rise, the family were known as ‘The Hillbillies’.

One of four children, Daisy Hannah Hill was only sixteen years old when she met Walter. She was an unworldly young girl, short and squat of figure with a plain face and a gap between her two front teeth. Daisy was flattered and surprised by the attentions of this mature man, and accepted Walter’s invitation to take a turn with him on the swing-boats. They whooped excitedly as they rode through the air above the green countryside, marvelling at how far they could see.

They courted for a while as Walter continued to live at Preston, a half-hour walk from the home of Daisy’s parents. He then took a job as a cow-man, like Daisy’s father.

The village of Much Marcle

Photo Credit: WikipediaWalter married Daisy at St Bartholomew’s on 27 January 1940. Before the service, friends and family gathered under the ancient yew tree outside the church porch, making sure their ties were straight and their shoes clean. Where Walter’s first wife had been so much older than himself, there was comment among the guests that the second Mrs Walter West was a girl of only seventeen. Daisy wore a white dress with a veil, gloves, and little silver slippers; she carried tulips and a lucky horseshoe. The groom was a burly man who looked older than his twenty-six years. He was dressed in his good dark suit, draping his pocket-watch and chain across his waistcoat, and wore a carnation in his buttonhole. When it came to signing the parish register, Walter betrayed his lack of education by printing his name in large childish letters.

He had found living in Preston upsetting after Gertrude’s death, so the newly-married couple set up home at Veldt House Cottages, just off the A449 main road. Daisy fell pregnant with their first child almost immediately.

She was eight months into her term, and alone in the house, when there was a knock at the door one evening. Daisy did not like opening up when Walter was out milking, but the visitor would not go away, so she had little choice. Confronting her was a stern-looking policeman in full uniform. Daisy was such a nervous and unsophisticated young girl that she found the sight of the policeman deeply unsettling, even though there was nothing for her to worry about. He explained that there had been a road accident outside the cottage: a man had been knocked off his bicycle and the policeman wanted to know whether she had witnessed anything. Daisy gabbled that she had not, and quickly said goodbye. But the visit had so excited her that, by the time Walter returned home, his wife had gone into labour. A tiny baby daughter was born prematurely later that night and given the name Violet. She died in the cradle a few days later.

Walter and Daisy then moved into a red-brick tied cottage at a lonely but pretty junction in the village known as Saycells’ Corner. The surrounding fields were covered with wild flowers, and a footpath known as the ‘Daffodil Way’ cut across a nearby meadow.

Bickerton Cottage was almost one hundred years old, and very primitive. It had neither electricity nor gas, and its water was drawn from a well in the garden by hand pump. To the left of the front door was a living room with an antiquated iron cooking range; both this room and the scullery had stone floors and low ceilings. A small flight of narrow stairs led up to two box-like bedrooms. The windows of the little house were four tiny squares that looked out over an orchard of apple trees and, on the other side of the lane, a large willow. The Wests kept chickens and a pig in an outhouse behind the cottage; this was also where they emptied the bucket that was their only toilet.

Once settled in, Daisy became pregnant again. She took to her bed in late 1941 to give birth for the second time, groaning with pain throughout a bleak autumn night. A fire was built in her bedroom and water was set to boil on the range downstairs. Daisy could hear the barking of foxes and the hoot of owls as the clock ticked away the hours of darkness. At last, as the sky lightened with the dawn, a healthy baby boy was born, gulping his first breath at 8:30 A.M. on 29 September 1941.

Four weeks later the proud parents carried their son down the lane, through the gate of St Bartholomew’s and into the chill of the nave. The Reverend Alexander Spittall bent to his work over the Norman tub font. He murmured the baptism, as the water trickled through his hands, naming the screaming infant Frederick Walter Stephen West. It would soon be abbreviated to Freddie West and, later on, to Fred West.

The joy and pride that Daisy felt were obvious for all to see. She took little Freddie to her bed each night, where she cuddled and petted the boy, often to the exclusion of her own husband. Hers was a beautiful baby: the curly hair that would later grow so dark was straw-yellow at first, and everybody marvelled at his astonishing blue eyes, shining like two huge sapphires. Daisy displayed Freddie’s christening card in a prominent position in the cottage. Illuminated in gold, red and blue like a page from a sacred book, the card read: ‘He that Believeth and is Baptised shall be Saved.’

Daisy gave birth to six more children over the following decade, in conditions of considerable poverty. For several years it seemed as if she had hardly given birth to one child before falling pregnant with the next.

The Second World War brought the additional hardship of rationing to the village. Walter earned only £6 per week, and the family quite literally had to live off the land. Windfall cooking apples and other fruit could be collected free from the orchard behind the cottage; chickens were kept for eggs and to provide a bird at Christmas. Walter brought pails of unpasteurised milk home from the farm each day, and in the evening and at weekends, tended his vegetable garden. Daisy baked her own bread and worked at her laundry in an iron tub behind the cottage. As she washed, Daisy cooed and fussed over Freddie, who stared back at her from his cradle with his big blue eyes.

The next baby, John Charles Edward, arrived in November 1942, just thirteen months after Fred. The relationship between the two boys would be the closest and most complex of any of the children. Walter and Daisy seldom left their sons alone, and seemed to care for them very much. John Cox, who has lived next door to Bickerton Cottage since 1927, remembers: ‘They thought a lot of the children. If ever they went off, they took the kiddies with them on their bicycles.’

The West family in 1984

Photo Credit: WikipediaDaisy gave birth to her third son within eleven months of having John. David Henry George was born on 24 October 1943, when Fred was two, but suffered from a heart defect and died a month later. It was partly because of his death that Daisy wanted to move on from Bickerton Cottage.

They went to live at a house named Hill’s Barn in the village. Daisy again fell pregnant. Her first daughter, Daisy Elizabeth Mary, was born in September 1944, and came to look most like her mother: they would be known to the family as ‘Little Daisy’ and ‘Big Daisy’.

In July 1946 the family moved for the last time, to the house where Fred grew up. Moorcourt Cottage was tied to Moorcourt Farm, owned by Frank Brookes, where Walter found work tending to the milking herd and helping with the harvest. Despite being called a ‘cottage’, it is actually quite a large building, semidetached with two chimney stacks and a dormer window set in the tiled roof. It stands on the outskirts of Much Marcle at a bend in the Dymock road, surrounded by open country. Looking out of the front windows there are uninterrupted views of the fields stretching away to May Hill in the distance. Cows low in the meadows, and the spire of St

Bartholomew’s, within an embrace of yew trees, is just visible over to the right of the panorama.

In the autumn after they moved into Moorcourt Cottage, Daisy gave birth to her final son, Douglas. At first he shared his mother’s bed, as the other babies had, but was then put in with Fred and John. Kathleen – known as Kitty, and the prettiest of the girls – was born fourteen months later; Gwen’s birth garden by hand pump. To the left of the front door was a living room with an antiquated iron cooking range; both this room and the scullery had stone floors and low ceilings. A small flight of narrow stairs led up to two box-like bedrooms. The windows of the little house were four tiny squares that looked out over an orchard of apple trees and, on the other side of the lane, a large willow. The Wests kept chickens and a pig in an outhouse behind the cottage; this was also where they emptied the bucket that was their only toilet.

Once settled in, Daisy became pregnant again. She took to her bed in late 1941 to give birth for the second time, groaning with pain throughout a bleak autumn night. A fire was built in her bedroom and water was set to boil on the range downstairs. Daisy could hear the barking of foxes and the hoot of owls as the clock ticked away the hours of darkness. At last, as the sky lightened with the dawn, a healthy baby boy was born, gulping his first breath at 8:30 A.M. on 29 September 1941.

Four weeks later the proud parents carried their son down the lane, through the gate of St Bartholomew’s and into the chill of the nave. The Reverend Alexander Spittall bent to his work over the Norman tub font. He murmured the baptism, as the water trickled through his hands, naming the screaming infant Frederick Walter Stephen West. It would soon be abbreviated to Freddie West and, later on, to Fred West.

The joy and pride that Daisy felt were obvious for all to see. She took little Freddie to her bed each night, where she cuddled and petted the boy, often to the exclusion of her own husband. Hers was a beautiful baby: the curly hair that would later grow so dark was straw-yellow at first, and everybody marvelled at his astonishing blue eyes, shining like two huge sapphires. Daisy displayed Freddie’s christening card in a prominent position in the cottage. Illuminated in gold, red and blue like a page from a sacred book, the card read: ‘He that Believeth and is Baptised shall be Saved.’

Daisy gave birth to six more children over the following decade, in conditions of considerable poverty. For several years it seemed as if she had hardly given birth to one child before falling pregnant with the next.

The Second World War brought the additional hardship of rationing to the village. Walter earned only £6 per week, and the family quite literally had to live off the land. Windfall cooking apples and other fruit could be collected free from the orchard behind the cottage; chickens were kept for eggs and to provide a bird at Christmas. Walter brought pails of unpasteurised milk home from the farm each day, and in the evening and at weekends, tended his vegetable garden. Daisy baked her own bread and worked at her laundry in an iron tub behind the cottage. As she washed, Daisy cooed and fussed over Freddie, who stared back at her from his cradle with his big blue eyes.

The next baby, John Charles Edward, arrived in November 1942, just thirteen months after Fred. The relationship between the two boys would be the closest and most complex of any of the children. Walter and Daisy seldom left their sons alone, and seemed to care for them very much. John Cox, who has lived next door to Bickerton Cottage since 1927, remembers: ‘They thought a lot of the children. If ever they went off, they took the kiddies with them on their bicycles.’

Daisy gave birth to her third son within eleven months of having John. David Henry George was born on 24 October 1943, when Fred was two, but suffered from a heart defect and died a month later. It was partly because of his death that Daisy wanted to move on from Bickerton Cottage.

They went to live at a house named Hill’s Barn in the village. Daisy again fell pregnant. Her first daughter, Daisy Elizabeth Mary, was born in September 1944, and came to look most like her mother: they would be known to the family as ‘Little Daisy’ and ‘Big Daisy’.

In July 1946 the family moved for the last time, to the house where Fred grew up. Moorcourt Cottage was tied to Moorcourt Farm, owned by Frank Brookes, where Walter found work tending to the milking herd and helping with the harvest. Despite being called a ‘cottage’, it is actually quite a large building, semidetached with two chimney stacks and a dormer window set in the tiled roof. It stands on the outskirts of Much Marcle at a bend in the Dymock road, surrounded by open country. Looking out of the front windows there are uninterrupted views of the fields stretching away to May Hill in the distance. Cows low in the meadows, and the spire of St Bartholomew’s, within an embrace of yew trees, is just visible over to the right of the panorama.

In the autumn after they moved into Moorcourt Cottage, Daisy gave birth to her final son, Douglas. At first he shared his mother’s bed, as the other babies had, but was then put in with Fred and John. Kathleen – known as Kitty, and the prettiest of the girls – was born fourteen months later; Gwen’s birth in 1951 completed the family. Daisy, having borne eight children in ten years, was now a heavy-set 28-year-old woman, hardened by life and quite different in looks and character to the timid teenager Walter had married.

Conditions at Moorcourt Cottage were basic. Eight slept in three cramped bedrooms: one for Mr and Mrs West, one for the three girls, and one for the boys, where Doug took the single bed and Fred and John shared the double. A tin bath was set in front of the parlour fire on wash nights, the children bathing under the watch of a pair of crude ornamental Alsatian dogs Walter had won at the Hereford Fair. Toilet facilities consisted of a simple bucket which had to be emptied each morning into a sewage pit, and rats were a constant pest. When Daisy saw one crossing the yard, she would blast at it with Walter’s shotgun – one of Fred’s abiding memories of his mother was of her shooting at ‘varmints’.

Of the six surviving children, Fred was his mother’s favourite. Coming after the tragedy of Violet’s death he was particularly precious; the son that Walter had wanted and the answer to Daisy’s prayers. As the baby grew up he could do no wrong; younger brother Doug described Fred as ‘mammy’s blue-eyed boy’. Daisy believed whatever Fred told her and took his side in squabbles between the children. For his part, Fred adored his mother and did exactly as she said.

The bond between them was perhaps unnaturally close. ‘Fred came first with Daisy, even in front of Walter. She thought the world of Fred,’ says her sister-in-law, Edna Hill. Partly as a result of this mollycoddling, Fred was a spoilt, dull and introverted child.

He was also scruffy. Daisy did her best to dress him nicely, in baggy shorts held up with braces, cotton shirts and sleeveless Fair Isle sweaters, but Fred always managed to look unkempt. Thick, curly brown hair grew up in a little bush on top of his head – just like his mother, whose looks he had inherited. Doug and John looked more like their father, and also got along with him, which Fred never did. There had been an awkwardness between father and son from the day Daisy brought Freddie into her bed.

Walter was well-liked in the village. He was a regular at the Wallwyn Arms on Saturday nights, and was sociable enough to organise the once- or twice-yearly village outings to the seaside, usually to Barry Island in South Wales. The day trips were the only holiday most of the villagers ever had, and they would pose for group photographs upon arrival to mark the occasion. Fred tends to look happy when he is photographed with his family, as long as his father is not in the frame. One snapshot shows Fred laughing uproariously with brother Doug as his mother clowns about with a neighbour. But when Walter’s stern face was in the picture, as it is in the surviving photograph of the Barry Island trips, Fred looks distinctly uncomfortable.

At the age of five, Fred was enrolled in the village school – the only one he ever attended, serving for both his junior and senior education. The backwaters of Herefordshire were slow in improving education standards after the war, and there was no secondary school in the area until 1961. The West brothers walked the two miles there and back every day, joining up with groups of other local children along the way.

Discipline was strict. Classmates remember Fred as being dim, dirty and ‘always in trouble’ because of his slovenly performance. He was regularly given the slipper. After the age of eight, he was old enough to be caned along with the rest of the children. Daisy was outraged by the regular punishments which Fred tearfully reported back to her. His class squealed in delight at the sight of Mrs West, dressed in one of her big floral frocks with her hands on her hips, haranguing their teacher after Fred had been hit. Fred became known as a mummy’s boy partly because of these scenes, and was repeatedly mocked and bullied.

After school, and at weekends, the children were expected to work. If Fred or his brothers and sisters wanted to buy an ice cream or a bar of chocolate, they had to earn the money to pay for it. There were also regular household chores, like chopping wood for the fire, that they had to carry out for no reward.

The jobs they worked at outside the house followed the seasons of the year. Spring found Fred leading his younger brothers and sisters on an expedition up the Dymock road to Letterbox Field, where they would gather bunches of wild daffodils to sell at the roadside: the countryside around Much Marcle is famous for daffodils and a blaze of colour in the spring. Years later, Fred stole back across the same fields to bury the corpse of his first wife.

In the long dog-days of summer the local women and children rose early to meet the hop truck. This rumbled out of the village along dusty lanes to the pungent hop fields, where they worked until the light faded. They also picked strawberries and other soft fruit. The children, with their own little baskets, toiled alongside the adults, their fingers becoming sticky as they worked.

Harvest promised the exciting summer sport of ‘rabbiting’, which in turn would lead to delicious pies and roasts for the undernourished families. Beaters walked through the wheat just before the harvesting machines began to work; then boys, armed with sticks, followed along the edges of the field and clubbed any rabbits that sprang out. The cull was a necessary part of feeding the poor of the village, and the rabbits were shared out at the end of the day with an extra one or two going to large, needy families like the Wests. ‘They were for eating, oh aye,’ says Doug West, licking his lips. ‘We would take them home, skin them and eat them. My mum was a good cook – rabbit stew, roast rabbit, anything.’

Autumn evenings were spent at home, listening to the Dan Dare adventure series on the radio and playing darts. The Wests owned a wind-up gramophone complete with a collection of scratchy 78s. At one stage, Fred took up the Spanish guitar, but he had little patience and the instrument soon became an ornament hung up on the wall in the front room. During the severe West Country winters, the children pulled on their moth-eaten cardigans and went sledging on Marcle Hill.

Fred was a quiet boy, with few friends of his own, relying on his family, particularly John, for companionship. Although John was a year younger, he was physically stronger than Fred and, probably out of jealousy of his favoured brother, bullied him. The third boy, Doug, who was small enough to be left out of their fights, remembers that ‘John used to beat the hell out of Fred’.

Walter milked the herd morning and evening. On Sunday Daisy would sometimes keep him company, leaving the children on their own, and this is when the trouble often started. Fred developed the habit of going outside the cottage and pulling faces at John through the window, until his younger brother became so enraged that he punched at Fred. The windows were made of small panes and John’s little fists were enough to knock the glass out. Naturally Walter was furious when he returned, warning them not to do it again and threatening a beating if they disobeyed him. Sometimes he would be provoked into taking the thick leather belt from his work trousers to hit the boys.

Fred and Rose West

Photo Credit: Imdb.comThe Wests were cut off from the world in their lonely cottage, and it is possible they became closer than is natural. There have always been rumours in the village that Daisy West harboured something more than motherly love for Fred – it is said she took her eldest son back into her bed when he was aged about twelve, and that she seduced him. This would not have been such an unusual act for a community like Much Marcle: deviant sex was not uncommon in the Herefordshire countryside. In Cider with Rosie, for example, his account of an idyllic childhood between the wars, Laurie Lee wrote about a community very similar to Much Marcle, pointing out that sexual transgressions ‘flourished where the roads were bad’.

Even if it is true that Daisy seduced Fred – and her family cannot confirm the story – it was probably Walter who was the dominant influence upon Fred’s emerging sexuality. In later life Fred often spoke about his father’s sexual appetites, claiming Walter indulged in one of the greatest taboos of all: having sex with children. Fred claimed that Walter abused young girls, and spoke openly about it, saying that what he did was natural and that he had a right to do so. Fred grew up with exactly the same mentality, never thinking that having intercourse with a child might be wrong. He maintained that ‘everybody did it’.

Away from home, Fred’s first sexual experiences took place in the golden fields around Moorcourt Cottage. Shortly after he entered puberty, Fred was taking part in fumbling sex games here. ‘We used to dive in the hay, take pot luck and go for it,’ he later bragged, saying that he had cared little about the age or identity of the girls involved.

Fred’s formal education was soon over. He had learned little at school, and left at the age of fifteen without taking any exams, being barely numerate and unable to read or write beyond the level of a seven-year-old. He had displayed some talents, though: Fred was artistic and drew with instinctive accuracy; in his final years at school he had taken woodwork classes and showed an aptitude for practical work, constructing a three-legged milking stool and a bench. Both of these were presented to his mother.

He went to work with Walter on Moorcourt Farm and the neighbouring Bridges Farm. The land was a mixture of arable and livestock; corn and potatoes were grown, and cows and sheep reared. As the youngest labourer, Fred had to muck in, doing whatever jobs the older farm hands passed on to him.

It was an unkempt, dull-looking youth who stood in mud up to his Wellington boot tops each day. His brown hair was uncombed and his old checked shirt torn. Tufts of adolescent beard stuck out from his chin, and his teeth were yellow because he rarely bothered to clean them. When asked a question, Fred would look away and either mumble or gabble his answer, making it hard to understand what he said or thought.

But there was one sight guaranteed to make him pay attention – and that was if a girl walked down the lane. Then Fred’s startling blue eyes would open wide and his young, monkey-like face would break into a gap-toothed, lascivious grin.

Want to keep reading? Purchase your own copy of Fred & Rose at the links below!

Featured photo: Hunter Cosford / Unsplash