When it comes to disability representation, fiction often falls short. Frequently, disabled folks are framed as powerless, as inspirational figures for able-bodied people, or as horrible monsters whose internal evil is being displayed through their disability.

These depictions often leave real disabled people feeling undervalued and support preexisting stereotypes about disability.

This is a real shame, not only for societal progress, but also for the stories themselves.

Realistic representations of disability offer an amazing opportunity to explore new ways of approaching plot and character development that are more inclusive and accurate to actual human experience. After all, death comes for us all, and disability comes for most of us.

However, once in a while you find a treasure of a book that includes perspectives that are often ignored.

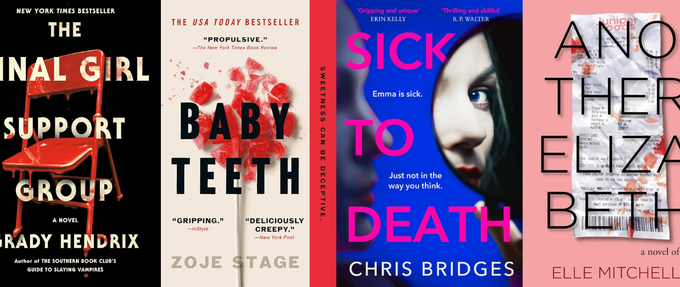

Here are six horror and dark thriller books with disabled representation.

.png?w=640)

Baby Teeth

Suzette is a talented artist turned stay-at-home mom due to Crohn’s Disease. Past traumas drive her to demand perfect behavior from her daughter, Hanna.

Hanna herself feels nothing but rejection from her mother and wishes Suzette gone, leaving Hanna and her perfect father alone together, forever. Unluckily for Suzette, Hanna is a resourceful little girl and has a plan.

Stage’s interweaving of Suzette’s past and current experiences with Crohn’s Disease shine, creating a complex character it is easy to both root for and disdain.

Combine this with depictions of mental health issues, gendered expectations of parenthood, a wicked child, and a propulsive plot, and you’ve got quite the page-turner.

Sick to Death

Emma is sick, diagnosed with a functional neurological disorder. Doctors can’t find any organic cause, so her providers and family doubt her disability. If people aren’t expecting too much from her, they’re expecting all too little.

Then she meets Adam: a handsome doctor smitten with her. The only problem is his wife, Celeste, who is wealthy and abusive. Emma has the perfect solution. Who would suspect her of murder? Emma is sick.

Bridges has crafted a thriller perfect for fans of ‘Gone Girl’, but with an added layer of complexity from the main character’s invisible illness. A massive amount of care went into centering Emma’s experience with disability without removing her agency.

The eventual twist is truly shocking, and once the story gets going, this book will effectively be glued to your palms.

The Shape of Water

In 1962, Elisa Esposito is a nonspeaking woman who communicates primarily through sign language. She leads a simple life as a janitor at a research center in Baltimore until she sees something she wasn’t supposed to: an amphibious man who is slated for dissection in the hopes of an advancement in the Cold War arms race.

But the creature is no mere animal, and soon Elisa realizes he is capable of complex emotion and communicating with her, and the pair grow close. Soon, Elisa is engaged in an action-packed race to rescue her fantastical love.

This book is the novelization of the 2017 film The Shape of Water. Novelizations can often get a bad rap, but this one stands out, filled with gorgeous writing.

Elisa being nonspeaking is an important aspect of the plot without being her only defining characteristic, and having a nonspeaking main character and romance interest allows the novelization to add character depth and plot complexity through internalized thoughts.

The story stands at the crossroads between a fairy tale and a gritty, Cold War horror and is a unique read.

The Final Girl Support Group

Lynnette is a real, actual final girl who survived a real, actual massacre. She’s been meeting with a support group for final girls for years, and otherwise rarely leaves her highly secured apartment thanks to overwhelming anxiety.

But when one of the final girls disappears, it becomes clear someone wants to finish what the original killers couldn’t.

Lynnette’s anxiety isn’t a quirk in this book, but is a large enough part of her life to impact her moment-to-moment choices and how seriously other characters take her. Written with Hendrix’s trademark fun style, it’s equal parts enjoyable and harrowing.

Of particular note is how injuries suffered by the characters impact them long-term; there are no miraculous recoveries from events that ought to be permanently disabling, which is refreshing in a mainstream horror novel.

Another Elizabeth

Elizabeth has too much going on: three jobs, a stage-four-clinger boyfriend, a recent diagnosis of hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (hEDS), and insatiable bloodlust.

As her hEDS progresses and her chronic pain increases, she realizes she’s running out of time to fulfill her dream of getting away with murder. Don’t worry, though: she only kills people who really deserve it. Usually.

Ideal for fans of ‘Dexter’, this novel takes the ‘inspirational disabled character’ trope and flips it on its head by introducing the reader to a woman who overcomes her disability in order to commit violent murders.

Physical limitations force Elizabeth to think on her feet as she commits her crimes, and she skillfully uses assumptions people make about her disability to her advantage.

With gratuitous dark humor and descriptions so gory they’ll make you squirm, this book breathes new life and nuance into the ‘disabled monster’ trope.

The Witch Elm

Toby is a charming Irish lad until he interrupts a robbery and is beaten within an inch of his life. He survives, but with a traumatic brain injury resulting in lost memories, as well as with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and less functionality in his leg and hand.

He moves in with his dying uncle right in time for a body to be found within a tree on the property, revealing a dark and twisted web.

This novel features the incredible sense of place typical of Tana French, and tackles both class privilege and the privilege of being able-bodied.

Toby is not a reliable or even likable narrator, but his experience of becoming newly disabled and how it forces him to reckon with his masculinity and place in society is relatable and well-rounded.

.png?w=640)