We don’t just tell ghost stories to scare each other. We tell them to make sense of loss, to explain the unexplainable, and sometimes, just sometimes, to keep the past alive.

Across centuries, these tales have echoed through ruined abbeys, crowded parlors, and flickering screens. They shift with our fears, evolve with our beliefs, and stubbornly resist being laid to rest.

To trace the journey of ghost belief is to trace a path through human thought itself: shadowed, searching, and never quite finished.

Even before the written word, societies told stories of spirits. Whether whispered beside hearth fires or painted on cave walls, the presence of the dead loomed over the living.

The ghost, then, is not a modern invention but a constant companion, evolving with language, ritual, and faith.

Let's take a look at how ghost lore has evolved across time, reflecting shifts in cultural identities.

Medieval Apparitions: 1100s–1400s

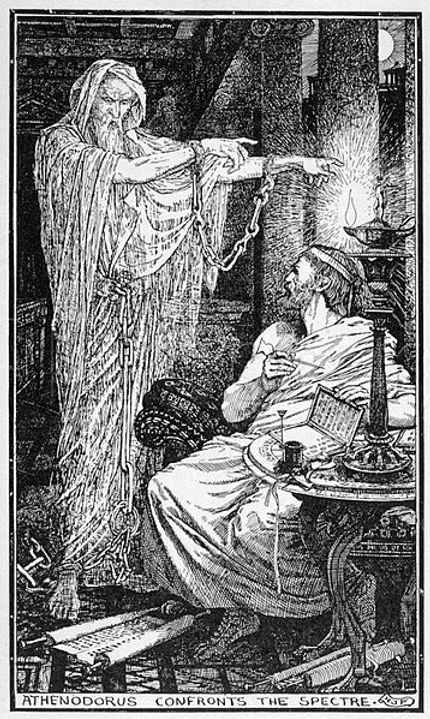

An illustration of Andrew Lang's "Athenodorus confronts the Spectre"

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsIn the Middle Ages, ghosts were not simply eerie anomalies; they were often souls with unfinished business.

Known in Latin texts as “revenants,” these apparitions were considered trapped between worlds, typically in Purgatory, that spiritual waystation introduced in the 12th century by Catholic doctrine.

These spirits were not aimless. They returned for a reason: to request prayers, seek restitution, or warn the living. A poorly performed funeral or unconfessed sin could tether a soul to Earth.

Ghost stories of the period, found in monastic chronicles or saintly vitae, were both theological instruction and spiritual caution.

Encounters were typically solemn. Ghosts emerged in dreams, on country lanes, or during vigils. Some wept; others warned of coming judgment.

They reinforced a world in which the living and dead were spiritually bound. Salvation was a shared journey.

The Reformation and a Crisis of Spirit: 1500s–1600s

Depiction of Hamlet's father's ghost

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsDuring the religious upheaval of the 16th century, ghost beliefs faced their first serious doctrinal challenge.

Martin Luther and John Calvin, central figures in the Protestant Reformation, rejected the concept of Purgatory. To them, souls went directly to Heaven or Hell—no spiritual pit stops, no return visits.

This shift was seismic. Suddenly, those midnight knocks and spectral whispers were rebranded, not as distressed souls, but as possible deceptions.

Ghosts, if acknowledged at all, were reframed by many Protestants as either figments or demonic tricks.

Still, old habits lingered.

In countryside villages and quiet parishes, ghost tales endured. People continued to tell stories, not necessarily because of doctrine, but because of experience, fear, or family lore.

Belief was no longer uniform; it was splintered.

The Enlightenment and Rational Rejection: 1700s–Early 1800s

As the Enlightenment dawned, intellectuals sharpened their scepticism. The supernatural came under fire. Philosopher David Hume famously argued that miracles (and by extension, ghosts) lacked credible evidence and should be dismissed unless proved beyond doubt.

This era prized logic, measurability, and repeatable phenomena. Ghosts, by nature elusive and personal, were now pushed to the margins—signs, some said, of backwardness or instability.

Yet the ghost did not go quietly. It shifted form, from theological warning to psychological metaphor. Writers wove spirits into Gothic novels, tapping into emotional undercurrents: remorse, lost love, ancestral guilt. Stories flourished even as official belief declined.

Some of these tales, found in chapbooks and penny dreadfuls, veiled social commentary.

A haunted castle might reflect a decaying aristocracy; a phantom bride, an unspoken scandal. In literature, the ghost retained its power—not as proof of an afterlife, but as a vessel for truth.

The Spiritualist Revival: 1840s–Early 1900s

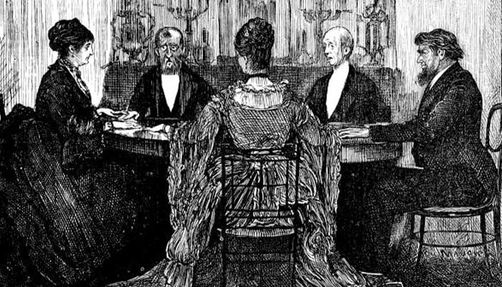

Depiction of a Victorian seance

Photo Credit: iStockThen, in the 19th century, the dead returned with a vengeance. Spiritualism, an international movement, promised communication with the beyond. Its growth coincided with high mortality rates and a desire for personal proof of an afterlife.

Public figures like the Fox Sisters and Daniel Dunglas Home gained notoriety for séances and spirit contact. Parlours filled with table-rapping and automatic writing. Ghosts were no longer warnings; they were guests.

Victorian literature responded in kind. Dickens’s tormented phantoms, M.R. James’s lurking spirits, Gaskell’s mourning spectres—all illustrated the era’s haunted conscience. Ghosts expressed moral imbalance, social injustice, and unburied secrets.

Psychical research also emerged, straddling science and mysticism. Societies formed to study unexplained phenomena using empirical tools, reflecting a culture both entranced and unsure.

Even Queen Victoria was rumoured to have sought comfort from mediums after Prince Albert's death.

Science, Psychology, and the Paranormal: 1900s–Late 20th Century

In the 20th century, ghosts wandered into new territories: the lab, the clinic, and the cinema.

Freud linked hauntings to repression; Jung viewed them as archetypes from the collective unconscious. Anthropologists began to catalogue ghost lore across cultures.

Technological advances added tools to the ghost hunter’s kit: tape recorders, thermometers, EMF detectors. The haunted house was no longer sacred ground; it was a site of experimentation.

Culturally, the ghost morphed again.

Films and radio dramas, from The Haunting to The Sixth Sense, made the ghost a media staple. Programmes like Most Haunted turned fringe belief into prime-time entertainment.

The spectral narrative stretched to match its century, reflecting fears of war, urban alienation, and even Cold War paranoia. Ghosts became not only emotional echoes but sociopolitical symbols.

Contemporary Hauntings: 2000s–Today

Modern day ghost hunters

Photo Credit: Wikimedia CommonsIn the digital age, ghost belief hasn’t waned—it’s diversified. Modern ghosts can be echoes of trauma, data glitches, quantum echoes, or even shared hallucinations. Everyone has a theory.

Belief remains resilient. Polls show millions still accept the possibility of spectral presences. But the explanations have multiplied and fragmented.

Haunting has gone online. Social media allows personal ghost experiences to be livestreamed, debated, or mythologized in real time. Ghosts have become content—part folklore, part performance.

Urban legends now spread in minutes. A video of a shadowy figure or a sound clip of whispered words can reach millions overnight. The ghost no longer waits in the wings; it is part of the algorithm.

And still, they trouble us. For all our data and diagnostics, we remain uncertain. Ghosts occupy that flickering space—between memory and mystery, science and story.

Conclusion: A Reflection of Ourselves

From medieval revenants seeking Masses to televised poltergeists flinging chairs, the ghost’s form may change, but its function endures. It reflects our fears, our losses, our longing to know what lies beyond.

Belief in ghosts is not a relic; it is a record. Of what we value, what we fear, and what we dare to imagine. As long as we fear death, the ghost will remain: knocking, flickering, whispering from the edge of our understanding.