On the afternoon of August 4, 1577, a violent storm moved across eastern England. Thunder rolled in from the coast. Lightning struck church towers. Rain fell hard enough to force doors shut.

In the market town of Bungay, parishioners later claimed that something else arrived with the storm.

According to accounts written soon after, a huge black creature burst into St. Mary’s Church during the height of the tempest. It moved through the nave with speed and force, killing a man and a boy before vanishing.

On the same day, just a few miles away at Blythburgh, another church was struck during worship. Here too, witnesses spoke of a “black dogge” tearing through the building, leaving destruction behind it.

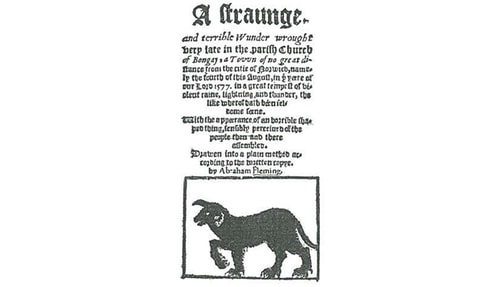

These events were recorded by the clergyman Abraham Fleming in a pamphlet printed later that year. Fleming framed the creature as demonic, possibly even the Devil himself, appearing in animal form. The language is vivid and fearful, shaped by a world in which natural disasters were rarely understood as random.

Modern historians point out that both churches were struck by lightning. Death and damage followed. In a sixteenth-century parish, terror would have spread quickly. It is not difficult to imagine how shock, grief, and belief combined into something monstrous.

What is harder to explain is why the Black Dog did not stay in 1577.

From Church to Road

If the legend ended with the Bungay and Blythburgh storms, it would be an interesting historical footnote. Instead, it grew legs.

By the eighteenth century, reports of a large black dog were appearing across Suffolk and Norfolk, usually far from churches and always on the move. The creature acquired a name: Black Shuck. The word likely comes from the Old English scucca, meaning demon or fiend, though its exact origin remains uncertain.

Descriptions settled into a familiar pattern. The dog was said to be large, sometimes unnaturally so. Its eyes were often described as glowing, red, or fiery. It was usually silent. It did not bark or growl. Most unsettling of all, it rarely behaved like a normal animal.

Witnesses claimed it walked beside them on lonely roads, just out of reach, matching their pace. Others saw it standing motionless at crossroads or near churchyards, watching without aggression.

In many cases, the encounter ended abruptly. The dog vanished. No sound. No trace.

Importantly, these stories were not always told as ghost tales. In rural communities, they circulated as warnings, reminiscences, or things that “happened once” to a neighbor or relative. They were folded into everyday conversation rather than performed as entertainment.

Essex and the Edges of the Map

Although Black Shuck is most closely associated with Suffolk and Norfolk, similar accounts appear in Essex, particularly in its coastal and marshland regions.

Here, the dog tends to haunt liminal places. Sea walls. Estuary paths. Roads that cut between villages after dark.

These are landscapes shaped by uncertainty. Tides shift. Fog rolls in. Distances are deceptive.

In Essex folklore collections from the nineteenth century, black dogs appear less frequently by name, but their behavior is familiar. A large dog was seen where no dog should be. A shape pacing a traveler, then dissolving into darkness. A presence felt more than clearly seen.

These stories rarely end in violence. The fear comes from proximity, not attack.

Not Always an Omen

Despite its reputation, the Black Dog was not universally feared.

In several Norfolk accounts, the dog acts as a guide. It accompanies travelers through dangerous stretches of road, especially at night, and disappears once they reach safety. In these stories, the dog’s presence is unsettling but ultimately protective.

This ambiguity matters. Folklore that survives tends to resist simple moral framing. The Black Dog is not consistently evil, nor reliably helpful. It appears when it chooses, behaves according to no clear rule, and leaves without explanation.

That unpredictability is part of its power.

Victorian Collectors and the Problem of Belief

By the nineteenth century, folklorists began writing these stories down in earnest. Ministers, antiquarians, and local historians collected accounts from parishioners who still remembered older tales or claimed personal encounters.

These collectors often struggled with tone. Some treated the Black Dog as superstition, recording it with mild embarrassment. Others clearly believed something real lay behind the stories, even if they could not define it.

What emerges from Victorian sources is a sense of persistence. The dog kept appearing. Not daily, not even regularly, but often enough that the legend refused to settle.

Descriptions remained strikingly stable across time. Size. Color. Eyes. Silence. Movement. Even skepticism did not erase these details.

Twentieth-Century Sightings

Reports did not stop with the arrival of electric light or the decline of rural isolation.

During the early twentieth century, Black Dog sightings were still being reported along country roads, particularly by cyclists, drivers, and night workers. These accounts tend to be brief and oddly restrained. A dog seen ahead on the road. Headlights approaching. The animal gone.

Witnesses often stressed that it did not move like a normal dog. It did not react to sound or speed. It did not flee. It simply ceased to be there.

Such accounts are easy to dismiss, and many have been. Yet the consistency remains difficult to ignore. Even modern stories echo older ones in structure and detail.

Influence Beyond East Anglia

The Black Dog’s influence extends far beyond the Eastern Counties.

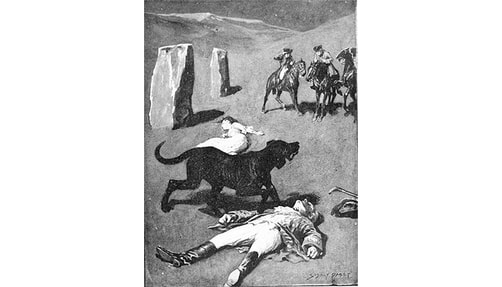

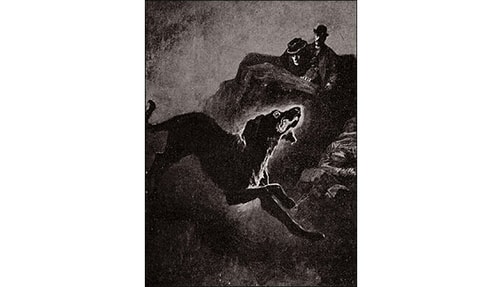

When Arthur Conan Doyle wrote The Hound of the Baskervilles, he drew heavily on British black dog traditions, relocating them to Dartmoor and amplifying their menace. The result fixed the image of a supernatural hound in popular imagination.

From there, the idea spread. Black dogs became shorthand for death, fear, or the uncanny in fiction, film, and music. Over time, the original regional character softened or disappeared altogether.

What was lost was subtlety. The Eastern Counties Black Dog is not theatrical. It does not roar or chase. It observes.

Landscape, Memory, and Fear

Why does this legend endure?

Part of the answer lies in the land itself. East Anglia is open and exposed. Roads stretch long and straight. The weather arrives suddenly. Before modern transport, traveling alone at night carried real risk.

The Black Dog occupies that space between fear and imagination. It gives shape to anxiety without resolving it. It appears at moments of vulnerability, then withdraws.

It is also deeply tied to memory. Many accounts are framed not as belief, but as something witnessed once and never explained. A moment that refuses to settle comfortably into rational thought.

Still Walking

Today, the Black Dog survives mostly in books, local histories, and quiet conversation. Few claim to see it. Fewer still speak openly about such encounters.

Yet the legend remains alive in the Eastern Counties, embedded in landscape and habit. It lingers on coastal paths and empty lanes, carried forward by repetition rather than spectacle.

Not as a monster.

But as a presence that walks beside you, briefly, before slipping back into the dark.

References and Further Reading

Fleming, A. A Straunge and Terrible Wunder (1577)

Brown, T. “The Black Dog in English Folklore,” Folklore, Vol. 69

Norman, M. Black Shuck: The Demon Dog of East Anglia

Simpson, J. British Dragons

Westwood, J., and Simpson, J. The Lore of the Land

Featured image: Vital Sinkevich / Unsplash