As soon as the reader opens this book, they are met with the following message:

“This book contains extremely disturbing material written by highly dangerous, psychopathic criminals. It is not for the faint of heart, or intended as a snug-as-a-bug bedtime read.”

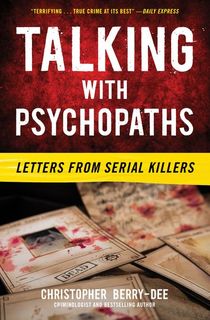

If not this foreboding message, then the title itself, Talking with Psychopaths: Letters from Serial Killers gives readers an indication as to what deeply upsetting content awaits them. Written by UK’s bestselling true-crime author Christopher Berry-Dee, the founder and former Director of the Criminology Research Institute (CRI) and former publisher and Editor-in-Chief of The Criminologist, has had the opportunity to interview and interrogate over thirty of the most nefarious killers. He was also the co-producer/interviewer for the documentary series The Serial Killers and has helped with criminal investigations around the world.

In Talking with Psychopaths: Letters from Serial Killers, Berry-Dee allows readers to study extensive interviews he conducted with convicted serial murderers, including the Genesee River Killer, The Death Row Teddy, The Ice Queen, The Want-ad Killer, and The Amityville Horror, among many others.

While being respectful of the innocent victims of these crimes, along with acknowledging the trauma that the convicted murderers’ loved ones must carry, the author analyzes the distressing correspondence he had with killers to better understand why they committed horrific crimes. Included in this book are exclusive scans of letters that grant serial killers the chance to explain their crimes and, in doing so, shed light on the inner workings of their dark minds.

Open Road will be re-releasing Berry-Dee’s successful Talking with Psychopaths series on August 22, along with the Talking with Serial Killers series. If you’re interested in learning what strategies investigators must use to get the facts of a crime or what serial killers are willing to divulge, then you should pick this one up.

Below is an excerpt of “Neville George Clevely Heath—a Letter too Far,” one of the unsettling chapters in Talking with Psychopaths: Letters from Serial Killers.

Buy the book, and don’t forget to look out for the rest of this chilling series, which re-releases on August 22, 2023.

Read an excerpt of Talking with Psychopaths: Letters from Serial Killers below—then purchase the book!

"Neville George Clevely Heath—a Letter too Far"

They’re weak and stupid. Basically crooked. That's why they’re attracted to rascals like me. They have all the morals of alley-cats and minds like sewers. They respond to flattery like a duck responds to water.

—NEVILLE HEATH, HMP PENTONVILLE, LONDON,

PRIOR TO HIS EXECUTION

From just those few lines, one can immediately smell arrogance in extremis. The writer is unrepentant. That he's also a narcissist and misogynist is patently obvious. And they come from a man about to meet his doom; he is not trying to eyewash us, as did Bundy.

By way of a brief background, during the night of 20 June 1946, a drunken Heath sadistically beat, whipped and murdered thirty-two-year-old Margery Gardner in his room at the Pembridge Court Hotel in Notting Hill, London.

Even without the 17 lash marks the girl's injuries were appalling. Both nipples and soft breast tissue had been bitten away and there was a seven-inch tear in her vagina and beyond.

—Home Office pathologist Professor Keith Simpson

The lash marks had been made by a leather riding whip with a diamond pattern weave; nine lashes were across the back between the shoulder blades, six across the right breast and abdomen and two on the forehead. The young woman's body had been bound hand and foot, the right arm pinned beneath the back. In the pathologist's opinion, the wounds to the vagina were due to a tearing instrument. In the fireplace was a short poker, which Professor Simpson believed may have caused the internal injuries. He surmised that Margery met her death by suffocation, either from a gag or from having her face pressed into a pillow. ‘If you find that whip, you've found your man, Simpson told the police.

Realising that the law would soon be on to him, Heath packed two suitcases into which he put Margery Gardner's bloodied clothing, the scarf he used to gag her and the cloth that had tied her wrists. He washed the riding whip, putting that in too before Oeeing to Brighton. And he had very good reason to leg it: already, a wanted notice, along with his photograph, was being circulated to every police force in England. Two days after the murder, Heath sent the following letter to Scotland Yard:

Sir,

I feel it to be my duty to inform you of certain facts in connection with the death of Mrs Gardner at Notting Hill Gate. I booked in at the hotel last Sunday, but not with Mrs Gardner, whom I met for the first time during the week. I had drinks with her on Friday evening, and whilst I was with her she met an acquaintance with whom she was obliged to sleep. The reasons, as I understand them, were mainly financial. It was then that Mrs Gardner asked if she could use my hotel room until two o'clock and intimated that if I returned after that, I might spend the remainder of the night with her. I gave her my keys and told her to leave the hotel door open. It must have been almost 3 a.m. when I returned to the hotel and found her in the condition of which you are aware. I realised that I was in an invidious position, and rather than notify the police, I packed my belongings and left.

Since then I have been in several minds whether to come forward or not, but in view of the circumstances I have been afraid to [...]I have the instrument with which Mrs Gardner was beaten and am forwarding this to you today. You will find my fingerprints on it, but you should also find others as well.

—Murder Casebook 15, Vol. 1 Part 15 — elsewhere with slight variations.

Image of Neville George Clevely Heath

Photo Credit: Featured photo: Murderpedia, Peter Gargiulo / UnsplashWhen we compare this letter, and Heath's attitude to Margery Gardner in particular, to the way he expresses himself in one of the last letters he penned before his execution (see the epigraph to this chapter), we find something interesting: he is intimating that the dead woman was of loose morals at once subconsciously revealing that he is also like-minded. Heath is also attempting to paint himself as a hapless victim ‘by association’; a jolly decent, hail-fellow-well-met, who was trying to accommodate Margery and who now finds himself in rather a dreadful fix because of it. The police, however, knew that Heath's appalling record of past crimes stretched way back: bigamist; arch-conman; fraudster; thief, wearer of military uniforms he was not entitled to wear; the list was almost endless. The police never received the whip in the post, nor did they believe a word of his bullshit story, so Detective Superintendent Tom Barratt was not impressed with the letter, which had been posted on 22 June 1946, postmarked Worthing, 5.45 p.m.

A taxicab driver named Harry Harter told police that he had dropped off Heath and Mrs Gardner at the Pembridge Court Hotel, where the man was registered as ‘Lieutenant-Colonel

N.G.C. Heath’. Police knew that Heath held no such rank — and he'd paid the cabbie 2s 2d for the 1s 9d fare. Harter recalled that both were highly intoxicated and they had their arms around each other as they staggered through the front door.

He stood out from other men, tall, blond proud and arrogant as a Nazi. He played I’m-hard-to-get. So I did. I won.

—A woman from Cambridge who refused Heath's oily advances

My book Talking with Psychopaths and Savages: Beyond Evil contains a detailed chapter on Heath's narrative, but the lady above sums his character up perfectly by describing him as ‘arrogant as a Nazi’. This underpins every single line of his correspondence from the death cell and his letter to the police, which he would have been far better off not sending at all—indeed, why he took away some of the crime-scene artefacts is anyone's guess.

Psychopaths such as Heath are control freaks, and here we find him being stupid enough to believe that elite Scotland Yard detectives would buy into all that he'd told them. But again, it is what is concealed between the lines that should interest us, because there we can see his way of thinking as clear as day. Assuming the moral high ground, he denigrates Margery Gardner, at once giving the police information known only to her killer and themselves, so apart from telling the police more or less what they knew already, he is trying to appear calm and sincere in an effort to convince them that he is telling the truth and to get the heat off his back. However, the police were now aware of his extensive criminal rap sheet that for most of his adult life he had been a con artist with a habit of assuming false identities; yet, so ingrained was his pathological mindset that Heath truly believed that law enforcement would buy into his story as hundreds of people had done before — but the police didn't!

On 3 July 1946, Heath met twenty-one-year-old Doreen Margaret Marshall, then serving with the WRNS, in Bournemouth. Four days later, her body was found in woodland at nearby Branksome Chine. She, like Margery Gardner, had suffered appalling injuries. The pathologist, Dr Crichton McGaffey, noted marks of attempted strangulation. Her throat had been cut twice. One rib had been broken and the others bruised, suggesting that the killer had knelt over her or jumped on the body, all of which shows a total hatred for young women in general. Abrasions on her wrists suggested that her hands had been bound. The hands themselves bore a number of defensive knife wounds, as if she had been trying to deflect the knife blows. Both of Doreen's nipples had all but been bitten off.

When Dorset police started to make enquiries, this arrogant, narcissistic man had the nerve to stroll up to the nearest police station to tell an officer that, in passing, he'd met Doreen the previous day, and that she'd had dinner with him at the Tollard Royal Hotel on the evening that she'd vanished. ‘I walked her part the way back to her own hotel, he told Detective Constable Souter, ‘and I have not seen her since.’ The sadosexual Heath was arrested that evening. The riding crop and some of Margery's clothing were found in his suitcases in the left luggage office at Bournemouth railway station. Nonchalant to the end, Heath sat calmly in his cell. When Albert Pierrepoint, the public executioner, arrived, Heath reportedly said: ‘Come on, boys, let's get on with it.’ He accepted the traditional offer of a glass of whisky to steady the nerves, adding: ‘While you're about it, you might make that a double, before, with a stiff upper lip, he strode unassisted to the trap to meet his doom.

Featured photo: Peter Gargiulo / Unsplash; Murderpedia