In pop culture, “Friday the 13th” is traditionally considered unlucky—though we encounter this date at least once or twice (sometimes, even thrice) in a year. The number 13 has been linked to death and misfortune in many cultures—some buildings even avoid having a thirteenth floor for this precise reason.

There are people so fearful of this date that they avoid any important work or social obligations that falls on such a Friday; thus, celebrating a birthday or a wedding or catching a flight is a complete no-no. Some are so paralyzed by fear that they even avoid getting out of bed that day—a fear that now has a scientific term “paraskevidekatriaphobia” (coined by psychotherapist Donald Dossey) to diagnose those suffering from it.

But in pagan traditions, Friday is often considered an auspicious day for love spells. In Norse mythology, Friday was the day for the Goddess Frigga, associated with marriage, motherhood and clairvoyance. It also signals the end of a busy week—the day most folks wrap up work early and make plans for the upcoming weekend. In esoteric sects, “13” is a very powerful number, linked to rebirth and resurrection.

So how did Friday the 13th become so unlucky? Or is it actually a very auspicious date, linked to divine feminine energies, that has been slowly and subtly demonized through the centuries by the forces of patriarchy? And can we reclaim its immense power?

How did Friday the 13th become unlucky?

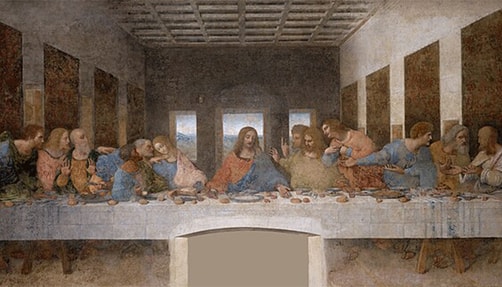

The exact origins of Friday the 13th as a signifier of bad luck are murky. Some scholars associate the superstition with Christianity—after all, Jesus was crucified on a Friday and there were thirteen people present at the Last Supper, including Judas who betrayed Jesus for thirty pieces of silver. Even now, in some cultures, having thirteen guests at a dinner party is considered a bad omen—as the first one to rise is the one most likely to die the soonest.

Other historians have noted a connection between the secret society of the Knights Templar and Friday the 13th. King Philip IV of France had ordered their arrest on October 13th, 1307 that fell on a Friday—a move that soon led to the dissolution of the illustrious order, though the day’s association with ill luck happened much later.

In fact, in 1907, Thomas William Lawson published a novel, Friday, the Thirteenth, a financial thriller about a stockbroker who manipulates people’s superstitions to cause chaos and panic on Wall Street and reaping an enormous profit.

Moreover, the widely successful horror franchise Friday the 13th that began with the release of the titular slasher movie in 1980 has also probably played a role in keeping the superstition alive in pop culture.

The number 13—History and Symbolism

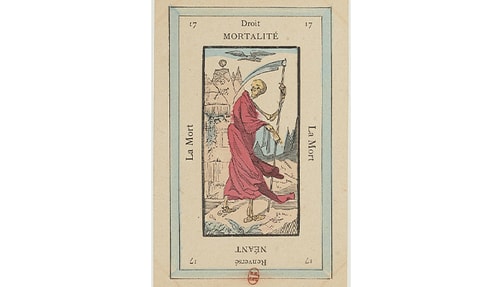

In tarot decks, the “Death” card (part of the Major Arcana) is associated with the number 13 and traditionally depicted as a hooded skeleton carrying a scythe.

But rarely does the Death card portend literal death—more often than not, it signals new beginnings and a need for change. In fact, the card actually associated with misfortune, upheaval, and destruction is the “Tower” (number 16).

But the fear of the number 13 is all-pervasive—appearing in multiple ancient cultures, including the Mayan and Babylonian civilizations. Yet there might be a mathematical reason for this, as the number 13 is preceded by the number 12.

The number 12 is significant as it as a high number of divisors (1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 12) and as a result, it was useful in a lot of calculations—we have 12 months in a year, 12 hours in a clock face, 12 inches make a foot and so on. Thus, number 12 represented a sense of completion whereas number 13 signaled a break from harmony.

Nevertheless, the number 13 is also associated with at least one complete cycle—the lunar cycle which typically completes in 28 days. And if we followed the phases of the moon instead of the movement of the sun to mark our calendars, we’d have 13 months in a year (28 days x 13 = 364 days).

Moreover, the lunar cycle is often aligned with women’s menstrual cycles and nature’s rhythms, and thus the vilification of number 13 can be linked to the suppression of feminine/lunar energies in favor of the masculine/solar cycles.

Friday—The Day of the Goddess

Finally, Friday is linked to at least two goddesses. In Norse myths, it’s associated with the goddess Frigga (Frigg’s Day/Friday) while in Greek/Roman traditions, it’s linked to Aphrodite/Venus, the goddess of Love.

Thus, Friday is a powerful day to tap into the sacred feminine energy to cast spells of love, fertility and creation. And with the number 13 being linked to renewal, it’s the perfect day to honor the cycles of life and the power of feminine energies to beget creation.

However, throughout history, patriarchal religions have always played a critical part in demonizing women—such as blaming Eve and Lilith for Adam’s fall from grace and humanity’s “original sin”—and forcing them to adhere to pre-defined roles for the benefit of men.

The history of witchcraft is bloodied with the names of innocent women who died for defying tradition and for daring to carve their own destinies.

Anything that gave women a sense of independence or agency was considered demonic and vilified, be it the folk medicines and home rituals passed down by a lineage of grandmothers, or even the animals they cared for, such as black cats.

Black Cat Symbolism

Along with Friday the 13th being associated with bad luck, it is also considered inauspicious to encounter a black cat while crossing the street. But cats were often considered to be witch’s familiars or demons in disguise.

Yet, the black cat is also a symbol of the goddess, particularly the Egyptian deity Bastet, who is often portrayed as a cat-headed woman who protected worshippers against diseases and evil spirits.

Demonization of the Feminine Dimension

Thus, Friday the 13th never started out as an unlucky day. With Friday being sacred to deities like Frigga and Aphrodite and 13 being a powerful lunar number, associated with divination, intuition and clandestine secrets, as well as renewals and rebirth, it’s an immensely powerful day to tap into the sacred feminine energies.

And yet the day’s association with misfortune is a natural result of the ongoing demonization of feminine power—via religion and other patriarchal power structures.

Instead of honoring the goddess, the average person is more likely to tread with caution and avoid taking any major decisions, effectively cutting them off from the divine well-spring of magic and abundance.

Just as feminine energies have been traditionally labeled as “bad” or “evil” by patriarchal forces, the immense magical potential of Friday the 13th has been suppressed by conformist societies all over the globe.

But with awareness and intent, we can slowly change the tide, reclaim what’s rightfully ours and transform the way the stories of women and witches have been told.

Featured images via Wikimedia Commons; Featured still via Paramount Pictures