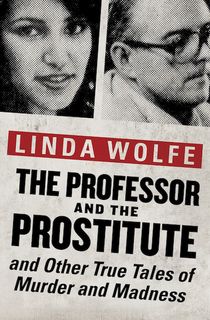

Read on for an excerpt from The Professor and the Prostitute by true crime reporter Linda Wolfe, where she shares her own first-hand experience with the twins, along with other true crime stories.

Then download the ebook at Amazon, Barnes & Noble and iTunes.

IN THE SUMMER of 1975, a pair of forty-five-year-old twins, their bodies gaunt and already partially decomposed, were found dead at a fashionable Manhattan address in an apartment littered with decaying chicken parts, rotten fruit, and empty pill bottles. The bodies were those of Cyril and Stewart Marcus, doctors who had apparently died, more or less simultaneously, as the result of a suicide pact.

Like many people, I was shocked by the information. Two things contributed to my astonishment. One was the men’s twinship, the doubleness that had given them a mutual birth date and now a mutual death date as well. Another was the men’s prominence; they had been among New York City’s most well-known obstetrician-gynecologists.

But if I was shocked, I was at the same time not surprised to hear of the death of the Marcus brothers, for I had known them, had once been a patient of Stewart Marcus. It was back in 1966, a year during which I paid several visits to his office but then abruptly decided not to continue seeing him. Though he was garrulous and even oddly confiding on one of my first two visits, on my third, he got angry about something—I no longer recall exactly what it was—and began to shout and scream at me. My husband was with me at the time, and I remember how, controlling an urge to respond in kind, he turned to me and said, “Let’s go. This man is obviously crazy.” Dr. Marcus seemed not to hear my husband’s derogatory remark, though it was made sharply and loudly. He just went on ranting and raving, and we felt that although the doctor was standing just across his desk from us, it was as if, in effect, he were somewhere else, somewhere very distant. We stood up and left.

No doubt it was because of that experience—when I had so clearly perceived the gynecologist’s distance from life, from reality—that I wasn’t altogether surprised to hear of his and his brother’s peculiar death. Indeed, a part of me wondered how anyone that disturbed and provocative had managed to function, cope, survive as long as he had. Nevertheless, I was immensely curious about how he had died, especially since there were a number of mysteries about what had occurred.

One mystery concerned the specific cause of death. A large number of empty barbiturate bottles were found in the apartment, and at first the medical examiner had assumed that the brothers had killed themselves by taking an overdose of sleeping pills. But autopsy tests revealed no trace of barbiturates in either body. The medical examiner’s office next concluded that the twins had died from an attempted withdrawal from barbiturates. Such withdrawal can, in the case of chronic barbiturate addicts—and by this time it had been established that both twins had been taking mammoth doses of Nembutal for years—be as fatal as the addiction itself by producing life-threatening seizures and convulsions. After the M.E.’s report, however, some experts questioned the finding, since the bodies showed none of the typical signs that accompany death by convulsion, such as bruises, tongue bites, and brain hemorrhaging. New tests were performed, and this time it was discovered that in Stewart’s body, at least, there were barbiturate traces, but not in Cyril’s. How Cyril had died remained a puzzle.

Another mystery was that Cyril had outlived his brother by several days. Police investigators learned that he had even left the apartment once Stewart was dead, only to return and die alongside him. Why had he left? And why, for that matter, had he come back?”

I began my investigation by talking, first, with police at the 19th Precinct, a few blocks from my home. Detectives from that precinct had been called to the apartment in which the twins had died—it was Cyril’s apartment on York Avenue in the East Sixties—after a building repairman discovered the bodies. A lieutenant described to me the scene the detectives had encountered. “There wasn’t an inch of floor that wasn’t littered,” he said. “The place was a pigsty.” He went on to explain that one of the twins had been found lying face down across the head of a twin bed, the other, face up on the floor next to a matching twin bed in a different room. The features of the one on the bed—Stewart, dead longer than his brother—had already begun to decompose.

“Not a pretty sight,” the lieutenant said. I nodded. “You want to see the pictures?” I said yes. But I couldn’t bring myself to look at the bodies. I concentrated instead on the rooms themselves, vast seas of garbage, of unfinished TV dinners and half-drunk bottles of soda, of greasy sandwich wrappers and crumpled plastic garment covers. “See the chair.” The lieutenant pointed at an armchair I’d hardly noticed, a-swim in the debris. “See what’s in the middle of it?” I peered but couldn’t tell. “That’s because you’ve probably never seen an armchair full of feces before.” The lieutenant guffawed. Then, serious and indignant, he said, “They used the chair for their toilet! Would you believe it!”

What I remember best about that encounter is that when I got up to leave, I noticed tacked to the back of the door a large print of the picture with the armchair. “A couple of the guys had it blown up,” the lieutenant, seeing me stare at it, explained. The pile of excrement in the center of the chair had been circled with a wax pencil, and scrawled across the circle were the words “East Side doctors!”

Want to read more from The Professor and the Prostitute? Download the ebook at Amazon, Barnes & Noble and iTunes.

Featured photo: Courtesy of The Airship