Clive Barker turned seventy-three years old on October 5, and Grady Hendrix says Barker is still painting his grotesque and beautiful art, but published his last book ten years ago and directed his last movie back in 1995.

In past interviews, Hendrix has mentioned his abiding love of paperback horror books from the ‘70s and ‘80s period. He stacks them up with care in his Manhattan home, and Clive Barker holds a cherished place in that collection.

Grady Hendrix is a New York Times bestselling novelist and screenwriter of seven novels and two books of nonfiction. One of those nonfiction books was the excellent Paperbacks from Hell, a history of the horror paperback boom of the seventies and eighties that won the Bram Stoker Award for Superior Achievement in Nonfiction in 2018.

In Hendrix’s Afterword for Clive Barker's newly reissued Books of Blood collection, he remembers first picking up Volumes one and three from a shelf on a rental cottage in St. Vincent when his father was teaching at an offshore medical school during the summer. They forever intimidated Hendrix from writing short stories as good as Barker's, so the New York City writer focused on novels instead.

Hendrix, the author of Witchcraft for Wayward Girls, How to Sell a Haunted House, The Final Girl Support Group, The Southern Book Club’s Guide to Slaying Vampires, and My Best Friend's Exorcism, is flat out exhausted, in between carrying out things from his mom’s house as he prepares to sell it.

Hendrix fans will know that his 2023 book, How to Sell a Haunted House, was deeply inspired by his mother, Carole Hendrix Grady, who died on February 3, 2022, after a two-year battle with Acute Myeloid Leukemia. He calls the whole multi-year experience a “nightmare” over Zoom, but he’s excited to take a break from edits on his next novel, his podcast Super Scary Haunted Homeschool, and cleaning up his mom’s house to talk about Clive Barker—one of his first influences for writing horror.

“I think that for horror, the Books of Blood is really a bit like Watchmen in '86,” notes Hendrix.

“It was sort of a ‘top this’ to an entire industry to do better than it. It really is a challenge that people still need to rise to in some situations. I feel like they're always one of those things that's like if you're writing horror, if you can't do better than the Books of Blood or you're not aspiring to do better than the Books of Blood, what are you doing?”

Hendrix describes the world where Barker dropped his gauntlet collection in the new Afterword: “When Books of Blood first came out, it was 1984 and Ronald Reagan was running for his second term, the internet didn’t exist, and the big summer movie was Ghostbusters."

Hendrix and his contemporaries Victor LaValle, Mick Garris, Eric LaRocca, Alma, Katsu, Sarah Langan, Paul Tremblay, John Langan, Cynthia Pelayo, and Hailey Piper all describe the indelible impact of Barker on their writing careers since each story left deep marks on their psyches. The horror writers join together for a bloody and beautiful chorus of remembrance in the Afterword.

Hendrix writes about the impact of the classic horror collection like a beautiful and calamitous event: The Books of Blood aren’t a pleasant pastime; they’re an act of violence that spurs real change. Reading these stories for the first time didn’t give any of us the warm fuzzies; they made us feel unsafe, queasy, sick, obsessed, and overwhelmed. They also liberated us. After all, the first step on the road to freedom is violence: the breaking of chains, the burning of temples, the destruction of your old identity.”

Clive Barker made his final conference appearance in 2024 to focus on his writing and continue painting. He slowed down a lot of his press interviews before that time, so Hendrix was a perfect person to talk about his work over Zoom during a crisp fall morning. We covered some of his favorite Clive Barker short stories, such as the straight-up monster story “Rawhead Rex” or the sexual ick fable “Pig’s Blood Blues.”

There’s also plenty of time spent with the stone-cold classics “The Hills, The Cities” and “The Forbidden,” before ending with the dark fantasy epic novel Weaveworld.

These stories all live in Barker’s strange universe and get an underlined focus from Hendrix beyond Barker’s own words about Books of Blood that can be found on his website or various archival interviews from the past forty years. The new version of Books of Blood Volumes One to Three is available now via Berkley after two solid years of Hendrix and other modern horror writers pushing for its reissue.

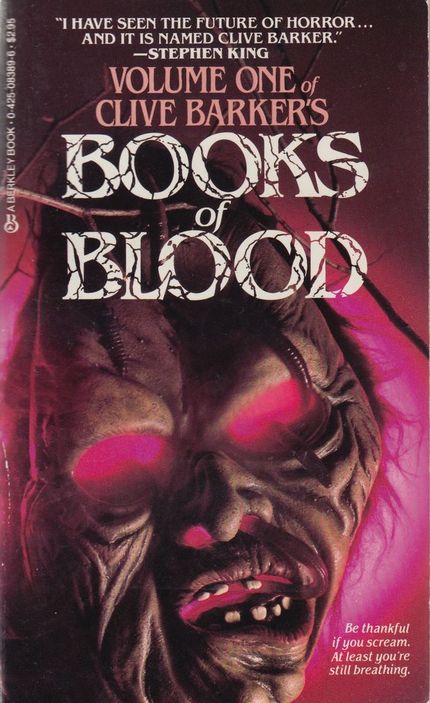

“The Hills, The Cities” - Volume One of The Books of Blood (1984)

Books of Blood - Volume 1

Hendrix calls “The Hills, The Cities” the “most famous story in the collection.” His horror writer friend, Paul Tremblay, said he first read the story and burst out laughing, and then had to go back and read it again. He couldn’t believe you could write a story like that.

Hendrix agrees with Tremblay: “You don't see it coming, and it's this new monster of a city that fights and walks made of its inhabitants, it's so new, and Barker visualizes it in so much detail that you're like, ‘I never would've thought of that.’”

The human reaction to the city beast is that they either lose their minds and hide from it or want to join up with its monstrous march. Hendrix also loves that the story has a normal gay love story embedded into the plot where it wouldn’t feel complete without that part.

“It’s a no apologies gay love story about a couple that's vacationing together, and like all couples, they bicker, and they have sex,” Hendrix says.

“They think one of them thinks he's smarter than the other. One of them thinks the other one talks too much, and I remember talking to Hailey Piper, who's a queer writer, and she was saying to her, what was so important, is that Barker wrote those characters and was basically saying, ‘you can have the queer sex and monsters, or you don't get any monsters. The two go together. You get the story the way I want it, or you don't get the story.’”

For many writers, gay and straight and across the spectrum, Barker’s story is revolutionary for being so ordinary and yet so mind-blowingly extreme in equal measure. That combination makes it so outside the norms of horror in the 1980s and pushed the genre forward.

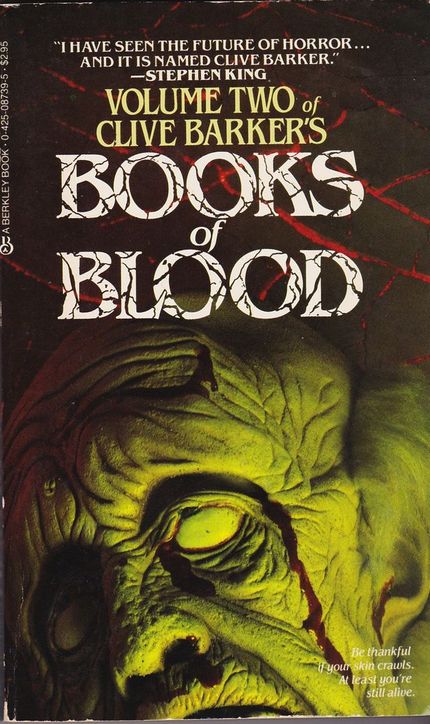

“Jacqueline Ess: Her Will and Testament” - Volume Two of Books of Blood

Books of Blood - Volume 2

Volume Two’s “Jacqueline Ess: Her Will and Testament” is about a woman who only discovers she has extraordinary powers when it drives her to the verge of suicide.

Barker said on his website what interested him most about Jacqueline “is the idea of characters who confront the ordinary, and find new meaning in the extraordinary, rather than simply finding some creatures or some forces that they must eradicate or exorcise in order to return to the norm that they had on page one.”

Barker's stories often end with scenes of revelation like this, where the main characters discover that the fantastical is better than the ordinary and not as frightening as when they started.

For Hendrix, “Jacqueline Ess” is a striking one that reveals new layers decades later. “I mean, that's a story that's so sexualin a real sense and physically grotesque that a lot of people really hold onto that one,” Hendrix notes.

Someone told Hendrix, as he was working on bringing Books of Blood back into a new 40th anniversary edition, that this story is reminiscent of the feelings from their youth.

“You see her body in this, and it's so mutable and malleable and shaped by how she feels because it's all about this woman whose body sort of mutates itself to whatever her lover's desire.” The other writer told Hendix that the story is what it feels like to be a teenage girl. “It felt like my body was out of my control, and it was always changing against my will and shaping itself into what other people wanted it to be.”

Going back to Barker’s old comments on the story, he noted that “many of the pivotal moments in our lives are very often rites of passage moments in which things are lost which can never be claimed again. Yet the territory ahead is, by virtue of the fact that it is new, also exciting and extraordinary.”

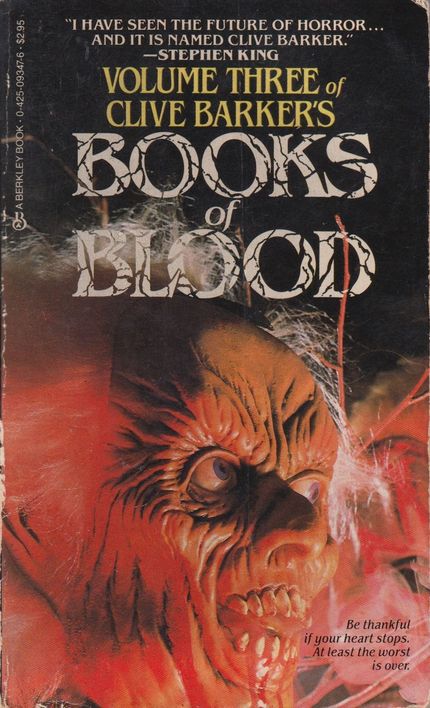

“Rawhead Rex” - Volume Three of Books of Blood

Books of Blood - Volume 3

Barker’s “Rawhead Rex” is not your run-of-the-mill monster story, according to Hendix. The pivotal difference is the end of the story. The epic short story has a structure similar to Alien or The Thing from Another World, but uses a rural setting in Kent, England.

The tale was later turned into the 1986 film Rawhead Rex, which Barker wrote but then renounced after being unhappy with the direction and overall production.

“[Barker] doesn't do those endings that a lot of people in horror do, which is a non-ending, Hendrix says. “For Barker, he doesn't just bring up a monster and set it loose in the British countryside. He engineers its destruction, which is really hard to do in a short story.”

The other element that makes “Rawhead Rex” such a unique monster tale is that it has 14 point-of-view characters throughout the story.

“Everyone, from the monster to, I think, a dog gets a brief point of view section. It's like most people stick with one character's point of view per story. Barker just nimbly leaps from one to the next, and it's just perfectly timed to be the next person who moves the story forward. And again, that thing most people do in a novel and he just packs it into a short story. Hendrix also loves the language Barker uses in “Rawhead Rex.”

“It's so evocative and so precise, and it also doesn't shy away from really going there, by concerns about morality or good taste. Hendrix says you can smell this story.

I open up to a random page from “Rawhead Rex” to read it to Hendrix, and we chuckle and marvel at how gross Barker describes the monster surfacing from a field: “His head was breaking surface now, his black hair wreathed with worms, his scalp seizing with tiny red spiders. They’d irritated him a hundred years, those spiders burrowing into his marrow, and he longed to crush them out.”

Gives you the shivers.

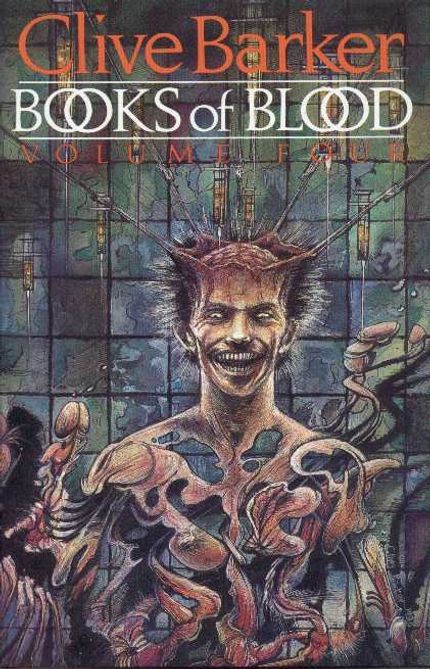

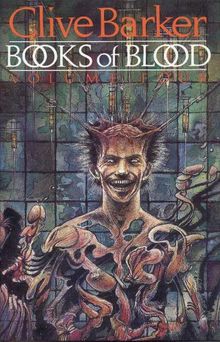

“The Body Politic” - Volume Four of Books of Blood (1985)

Books of Blood - Volume 4

“The Body Politic” is one of Barker’s most ambitious stories, Hendrix argues. “Everyone’s hands revolt against them and sever themselves from the wrist,” he enthuses.

“And on the one hand, there's this really funny kind of thing because the hands are all shouting revolutionary slogans with hand telepathy, and at the same time they're wreaking real violence. And people look at [David] Cronenberg movies and are like, ‘oh, there are new organs in this. It's all about the new flesh, and in the flesh makes it so literal and on the nose, you know what I mean? It's like, ‘forget humans, it's time for our hands to storm out and take over the world.’”

Hendrix says the concept is also a deeply rooted childhood fear that stays with you into adulthood. Everyone has had a brother or sister take their sibling’s hand and hit their own face before and giggle, “quit hitting yourself!”

Hands are symbols of potential revolt and chaos in popular media and literature as well. “There's that famous short story that got made into a movie, The Beast with Five Fingers,” Hendrix remembers. “Oliver Stone wrote “The Hand” with Michael Caine in it about a killer hand.”

Hendrix loves that Barker's story “The Body Politic” takes itself seriously and doesn’t just fall into a goofy tale about hands taking over the world. It’s more shocking and serious than its silly premise.

You can see Hendrix’s unique blend of humor and horror in his novels crawling out of this story’s primordial ooze.

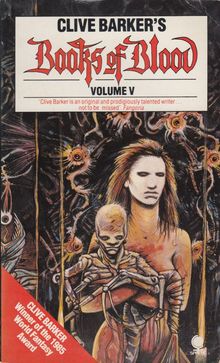

“The Forbidden” - Volume Five from Books of Blood (1985)

Books of Blood - Volume 5

The third major pillar of Barker is the Books of Blood, Hendrix notes. “I mean, it's six volumes. And he sort of wrote them all in one swoop, and I think they all appear between ‘85 and ‘86,” Hendrix says.” “And that was just a shot fired across the bow of horror to really make people sit up and pay attention because of how different it was.”

The final and fourth thing Barker is known for is his paintings and visual art.

“Mick Garris is a good friend of his; he's collaborated with [Barker] on a lot of projects, and he says he's still painting, but he's never stopped,” Hendix notes. “His paintings are really striking and beautiful and grotesque…they're really part of his vision.”

“One of the most iconic [Barker stories] is "The Forbidden,” from Volume Five, which became Candyman (1992),” Hendrix says. The story mixes many of the Barker pillars above.

“It's one of those stories. I mean, it's a woman on a housing estate that's sort of dilapidated and fallen into ruin. She encounters this spirit of vengeance, this black man. And there's so much tension packed into this story. And I don't mean tension, suspense, I mean tension. She's a white upper-middle-class academic, and the spirit of revenge was a poor working-class black man.”

Hendrix goes on about the sexual tension between the story's two characters.

“She's attracted to him, and it almost transcends sex. I mean, I guess desire is sexual, but she's attracted to him because he's so different, and it's just such a good story.”

The story keeps getting new movie adaptations, and Hendrix thinks the movies hold up because they feel like a Barker story and keep the tension found in the original story.

Weaveworld (1987)

Weaveworld

The longer Barker’s career went on, the more his novels required a bigger buy-in to read just one book. Hendrix noted that many of them were part of a longer series and are more of a “marathon,” whereas his famous short stories are a “hard sprint.”

“The fact that he can sustain his imagery and his imagination and his storytelling ability through these vast novels is pretty staggering,” Hendrix says.

“And for me, the one that hits the perfect balance between Clive Barker Horror Writer and Clive Barker, Epic Fantasy Novelist, is his second novel, Weaveworld, which is about a hidden kingdom sort of woven into the fabric of a carpet that people are running after. I'm amazed there's not a Game of Thrones-sized TV series out for Weaveworld.”

Hendrix typically goes into reading an epic fantasy book and sort of rolls his eyes with the inundation of lore, thinking it's going to be all “clashing armies and a lot of proper nouns.”

Barker keeps it really focused on precise individual characters and their interactions. Just like his short stories, the master of horror inhabits every point of view, from a criminal to a zombie to a human being just trying to make a living.

Hendrix loves Barker’s violence and sex inherent in his best short stories and novels, which were very appealing to a teenager when he first started reading, but he keeps coming back far into adulthood.

“These stories still work,” Hendrix says. “And for all of us, these stories were really, ‘here's what you can do, here's how explicit you can be. Don't be shy if it's a stupid idea; maybe it's stupid because you haven't explored it fully enough. Go all the way.’”

Hendrix notes throughout our conversation four things Barker is known for as a creator. The first is being a film director, most notably for Hellraiser, Lord of Illusions, and Nightbreed.

“I mean, Pinhead [from the Hellraiser series] has sort of entered the pantheon of horror movie icons very quickly, but that was sort of his biggest entry in his film career. He notes that Lord of Illusions and Night Breed have their devout admirers, but those movies were always viewed as failures.

Secondly, Barker is known for writing “big, fat, long novels that gradually started with The Damnation Game and went to Weaveworld, and as they progressed, they moved away from horror and incorporated horror, but became more dark fantasy epics.”

Featured image: Rosie Sun / Unsplash