Cathy Wood and Gwen Graham met as nurses at Alpine Manor, a senior living facility in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Cathy, a bleach blonde divorcee who gave up men and took up women, had a mean streak. She’d tease and play sinister jokes on the other nurses, creating drama in what should be a drama-free environment.

As for Gwen, she may have been new to the Alpine staff but her sexual preference – females – was anything but. Described as pug-nosed and eager to please, she fell for Cathy immediately. The two dated and even made a love pact to be together “forever and five days.”

It’s a relationship that sounds innocent – like puppy love you act out on the playground in grade school. But their nights of aggressive love making, drug use, and murderous plots were far from child’s play. Cathy called the shots; Gwen was the muscle. And the two ended up claiming the lives of at least six patients, smothering them in their beds.

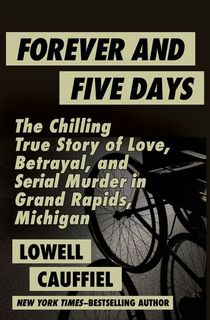

Lowell Cauffiel’s true-crime tale, Forever and Five Days, plays out like a big-screen crime thriller. It even ends with the women’s confessions. Get a sneak peek below at Cauffiel’s retelling of the duo’s first victim: Marguerite Chambers and the sexcapade they participated in afterward.

A low pressure front had just pulled a white sheet of snow over Grand Rapids as Ed Chambers arrived at Alpine Manor for his Sunday night visit. Later, the mercury would hit the single digits, the kind of cold that struck when skies cleared in the dead of the Michigan winter.

Inside, he called Marguerite’s name as he turned the corner into her room. He grasped her shaking hand once more. He spent about an hour with her, telling her things of little consequence, talking to her as though she were normal. He would never know if she understood. He stayed nearly an hour. It was between seven and eight o’clock when he rose to go.

On January 18, Marguerite Chambers was marking day 1,293 as a patient of Alpine Manor. She had been institutionalized nearly five years. Twelve years had passed since she had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease.

Outside 614-1, aides were working from room to room. They were rounding up some patients, changing others and preparing all of Alpine Manor for the night. Most aides were occupied. Others were taking midshift breaks. At 8:00 P.M., licensed nurses would begin going from room to room, passing out evening medication.

As Ed stepped outside, he noticed there were few cars in the lot. Most of them belonged to employees. Three inches of snow had kept many visitors home for the night. There was little traffic on Four Mile Road. The snow creaked beneath his feet. A light wind made the snaps on the Alpine flagpole ring in hollow tones.

The clanging seemed to sound deeper in the cold.

How Marguerite had always loved the waltzes. She had danced them freely, dipping and sweeping across the floor—one, two, three … one, two, three … one.

Strauss had no equal. The Emperor Waltz … Vienna Blood … Tales from the Vienna Woods. She loved the Blue Danube Waltz. It rushed and wavered, moving the spirit along, as though it were being carried away by the great river.

The Blue Danube was playing regularly in 614-1, once a week as a matter of fact. A regular visitor brought the music. She was a new face for Marguerite. The chipper activities staffer brought a portable tape player. She plugged it in, and then the Strauss waltzes began.

One, two, three … one, two, three … one.

In her predictable universe, Marguerite Chambers had come to experience two changes beginning in the days before Christmas. One was the music, courtesy of a new in-room program. The other was an aberration, an intrusion. It did not soothe her like the waltzes. It quickened the fiercest of all involuntary impulses. It unleashed her raw will to live.

If she could have articulated the first incident in detail, she might have reported it as a quirk, a momentary loss of respiratory rhythm, like a chronic snorer stuck between breaths. Then, the cessation came suddenly and with much fury. There was unrelenting pressure across her nostrils and the underside of her jaw. There was terry cloth, its loop pile so compressed it dug into her skin like dull darts.

Without air, she lost consciousness.

When she awoke—when she survived—her mind may still have been capable of associating the experience with a familiar face or a pair of hands or the smell of Sween Cream. On Christmas Day, she may have associated the attack with the touch of terry cloth, the touch of a wash towel around the lips.

These remained Marguerite’s secrets. Her nurse only knew that her pulse was running a little over a beat per second, that her blood pressure was in the normal limits for a woman of sixty years. She had been very restless the previous night, all through Alpine’s third shift. Her limbs were exceptionally kinetic. She ran a fever of 101 the night before. All the movement could easily have been caused by that.

After Ed left, it began.

There may have been some notice of the intruder’s presence. Or perhaps the attack came suddenly, and Marguerite was jolted from her sleep. The traverse rod hissed as a hand pulled the divider curtain. There may have been the sounds of a polyester uniform rubbing against itself. Two hands positioned her head, resting it squarely on the back of her skull. Maybe this was sudden. Or, maybe it was gentle, like an oral surgeon readying a patient for his handiwork.

Of one thing Marguerite Chambers was certain.

Air.

Quite suddenly, there was no air. There absolutely was none.

The terry cloth was rolled. One covered Marguerite’s nostrils. The other was under her chin. One squeezed, the other thrust up, violently, pushing her toothless gums together.

Marguerite began to thrash. Her groans were guttural, deep within her belly. As the need to breathe became more urgent, her cheeks began to puff and collapse. Her lungs were sucking for the pathetically few cubic inches of oxygen that were left there before her mouth was slammed shut.

Perhaps trauma stimulated memory, as can happen so near death. There was the old farmland in Walker. There was the nursery across the golden field. There were Ed, Jan, Gary and Ed Junior. The lake glistened at the family cottage. She loved waterskiing for the children, putting on a show. She loved scrabble and she loved dancing. The waltzes played. The Blue Danube. She was waltzing freely … one, two, three … one, two, three … one.

Perhaps not.

The muscles strengthened by her fetal rocking drew deep upon their incessant conditioning. In a great effort, she twisted her head.

But nothing could have prepared her for this.

Her last movements were spasmodic. In the end, in her final moments of consciousness, her eyes couldn’t help but look at the face above her. Michelangelo might have painted it on a Sistine Chapel cherub.

But it belonged to an angel of death.

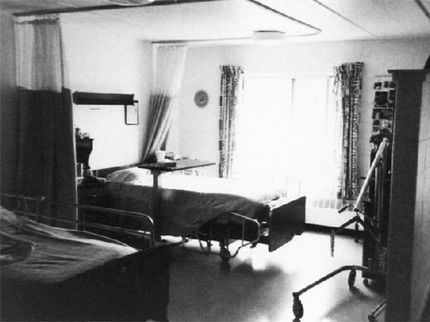

Inside a patient's room at Alpine Manor.

Both Cathy Wood and Gwen Graham were scheduled to be off on Monday, the day after Marguerite Chambers died. Tuesday, they were scheduled to work a double, beginning on second shift. Cathy called in an excuse for them both. Something was amiss in the basement.

“The water heater is broken,” she told a supervisor. “We’re waiting for a repairman.”

Cathy and Gwen were home drinking. They were drinking alone.

The hot water heater was located in the center of the basement, not far from the sewer drain and the little chimney door. Cathy later said she was especially afraid to descend the basement stairs during those two days.

“I thought maybe Marguerite would be down there and she would get me,” she said.

On Monday night, they played in the bedroom. One of them applied the wrist restraints, lashing the hands of the other to the bed. One of them took a pair of tube socks from the dresser, pulling them over her hands. One mounted the other, straddling the other’s body with her knees. One squeezed the other’s mouth and nose.

There would be no suffocation, only tears. The restraints rapidly were untied.

“I’m sorry,” one of them kept saying. “I’m sorry.”

Later, the 45 spun on the turntable. Mel Carter was singing once again.

“Hold Me. Thrill Me. Kiss Me. Make me tell you I’m in love with you.”

“I’ll love you forever,” Gwen and Cathy said.

Want to keep reading? Download the book at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and iTunes.

Featured photo courtesy of Kent County Sheriff's Department