Palermo, on Sicily’s northwestern coast, is a city rich in distinct cultural traditions—a result of centuries worth of influence from Romans, Phoenicians, Arabs, and Italians. A seaside town, Palermo easily attracts visitors with its sandy shores, abundant sunshine, and ancient architectural marvels.

Beneath the bustling streets of this charming city, however, is something quite macabre—a place where the dead remain frozen in time.

The Capuchin Catacombs of Palermo (Catacombe dei Cappuccini in Italian) are located on the outskirts of the city and house over 8,000 souls, including over 1,200 mummies. Bodies line the crypt walls from floor to ceiling—stacked upon shelves or propped up in alcoves, while others rest in deathly sleep in open caskets.

The site was founded in the 16th century when Capuchin friars ran out of space to bury their brothers. A crypt was constructed to house the blessed dead, starting with Silvestro of Gubbio. Interred in 1599, Silvestro can still be seen today as a jagged skull wrapped in navy blue cloth.

At first, only the bodies of monks were interred in the catacombs—but the site soon caught the attention of wealthy laymen looking for a prestigious site of everlasting slumber. Beginning in the seventeenth century, affluent families sent the bodies of their dearly departed to Palermo along with generous donations, in hopes that their kin could also be buried in the tombs.

The friars acquiesced. Additional rooms were constructed and corpses were stored by profession, gender, and social status. Soon the crypt became a labyrinthine monument to the dead.

Numerous techniques were used to preserve the deceased. Bodies were laid out on ceramic racks for dehydration. Some were bathed in vinegar and embalmed, while others were put to rest in sealed glass cabinets. Often, monks removed all organs and stuffed the cadavers with dried grass. Today, strands can still be spotted in some of the corpses, poking out through moldering funeral clothes and fragmented skin.

The final friar to be buried was Brother Riccardo in 1871. The site officially closed its doors in 1880, though interments continued into the early 1900s. One of the last burials was a little girl from Palermo, who became the crypt’s most famous eternal resident.

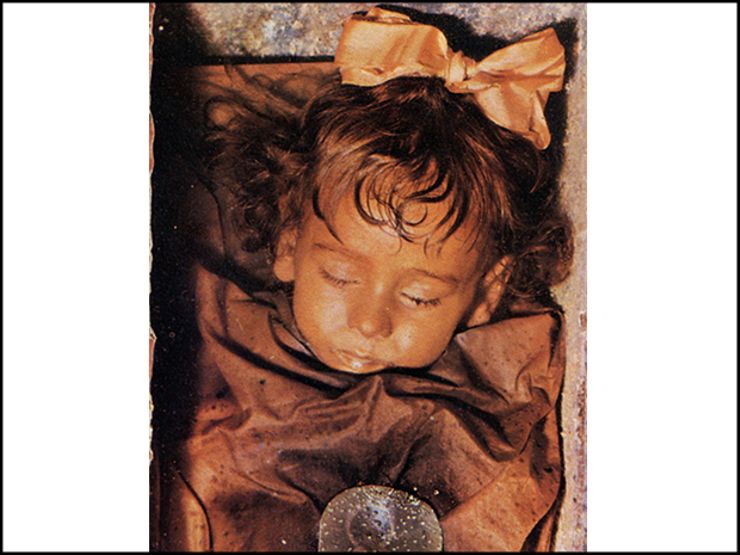

Rosalia Lombardo was just two years old when she died of pneumonia in December of 1920. Her father could barely face the reality of her child’s passing. So he had her embalmed. The process was a remarkable success; upon its completion, Rosalia’s complexion appeared warm and pink, with curls of flaxen hair cascading down her face.

Her corpse maintained its peaceful state with each passing year, earning her the nickname of the world’s most beautiful mummy. Amongst the desiccated bones and long-dead corpses of the Capuchin Catacombs of Palermo, angelic Rosalia still seems as if she were merely sleeping.

[via Palermo Catacombs]

All photos courtesy of Wikimedia Commons